Why Many with Multiple Incomes Still Rely on France’s Welfare System

In France, the CAF (Caisse d’Allocations Familiales) plays a vital role in supporting low-income households. As of the end of 2023, nearly 13.8 million households received at least one type of benefit from the CAF, such as family allowances, housing assistance, the activity bonus (prime d’activité), or RSA (Revenu de Solidarité Active). This broad social safety net highlights how deeply integrated public assistance is in French society.

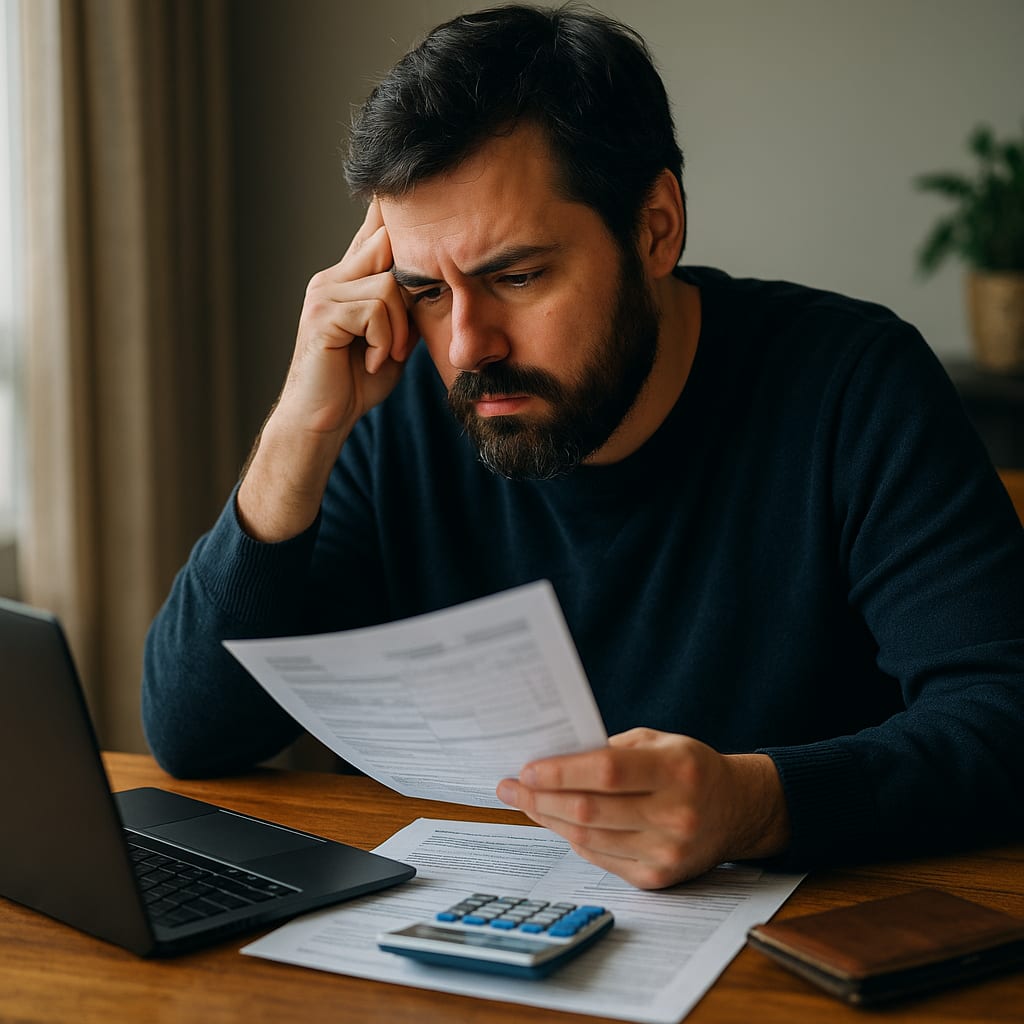

Among these recipients are people who actually have multiple sources of income: part-time or full-time jobs, freelance gigs, small businesses, or occasional side hustles. Yet they continue to receive aid from the CAF. This might seem paradoxical at first glance. Why would someone with several incomes still apply for welfare? Is this opportunism, or does it point to something deeper?

The first key point is that CAF benefits are means-tested, not exclusion-based. This means that benefits don’t disappear the moment you earn money. As long as a person or household’s total income stays below specific thresholds, they remain eligible for some support.

Take the prime d’activité, for instance. It is designed to top up the incomes of low-wage workers and is calculated based on around 61% of declared earnings, with a fixed base depending on household size. As a result, a person can earn income from work and still receive this bonus, along with other assistance like APL (housing benefits), as long as their income remains within the qualifying range.

This reflects a policy choice: rather than punishing people for working or pushing them off aid too quickly, the French system aims to encourage employment while cushioning financial instability. It’s not a handout for doing nothing. It’s a bridge to help those in fragile conditions stay afloat.

But why do people with several income sources still apply for help?

First, there’s the reality of work fragmentation. Many modern jobs are part-time, temporary, freelance, or seasonal. Even with two or three “jobs,” a person may not earn enough to cover basic living costs. This is especially true in urban areas where rent, food, transport, and childcare costs are high. The rise of the gig economy has amplified this issue—more people work more hours, but with less security and fewer guarantees.

Second, the cost of living in France continues to rise. Inflation has hit energy, groceries, and housing hard. Even someone with multiple incomes may find themselves short at the end of the month, especially if they support a family. The CAF’s assistance can make the difference between scraping by and living with a modest level of stability.

Third, the CAF adapts to income fluctuations quickly. Benefits like the activity bonus or APL are recalculated quarterly, based on recent earnings. This makes the system responsive to real-life changes, such as a drop in freelance income, an end to a temporary contract, or an illness that prevents work.

It’s also worth noting that many people who receive aid are not trying to “cheat” the system. In fact, studies suggest the opposite: 30% of eligible people don’t claim benefits they’re entitled to, often out of pride, confusion, or lack of awareness. Those who do apply often see welfare as a temporary help—not a lifestyle. Tools like mes-aides.gouv.fr now help French citizens estimate their rights transparently and with minimal bureaucracy.

Some people might ask whether this kind of assistance encourages complacency or dependence. But the data paints a different picture. Most recipients of CAF aid are either working or actively seeking employment. Those on RSA, for example, must commit to job searches or reintegration programs. The benefits are conditional, not automatic.

The debate shouldn’t center on whether people “deserve” aid if they have income. Rather, we should ask: Why does work alone no longer guarantee financial independence? What does it say about the structure of the labor market when someone needs three gigs and welfare to survive?

It’s also important to remember that having “multiple income sources” does not necessarily mean wealth. A person may drive Uber, sell things online, and work 15 hours a week at a café, yet still fall short of covering rent, bills, and food.

In this context, the CAF becomes more than just a safety net. It acts as a stability buffer in a world of volatility. It supports not only the unemployed but also the working poor, the freelancers between contracts, the single parents, and the part-timers navigating irregular schedules.

Is there abuse in the system? Of course—like in any bureaucracy. But widespread fraud is not the norm. The real issue lies in how the economy has changed, and how the old model—one stable job equals financial autonomy—no longer applies for many.

The CAF system also ensures regular income reporting and adjusts benefits accordingly. If someone’s earnings rise, their aid decreases. It’s a sliding scale, not a permanent fix. This ensures that help goes to those who need it most, while allowing for flexibility as situations improve.

To accuse people with multiple incomes of exploiting the system misses the point. Most are navigating a complex financial puzzle, trying to piece together a dignified life in an increasingly unstable economy. For them, welfare isn’t laziness—it’s survival.

Ultimately, CAF’s purpose isn’t just to compensate poverty, but to prevent it from becoming permanent. It’s a support mechanism that adapts to life’s ups and downs—job loss, illness, divorce, inflation, or simply the rising cost of basic living. It allows citizens to stay afloat while they find their footing.

The real challenge going forward is not punishing those who use the system correctly, but redesigning labor and social protections for the realities of today. Because as work becomes more flexible, more fragmented, and often more exhausting, welfare systems must be equally agile and compassionate.

In conclusion, many people in France with multiple income streams still rely on CAF benefits because their financial situation remains precarious despite their efforts. Far from being freeloaders, they are often overworked and underpaid—balancing jobs, responsibilities, and unpredictability. The CAF doesn’t make them rich. It helps them breathe.

About the Creator

Bubble Chill Media

Bubble Chill Media for all things digital, reading, board games, gaming, travel, art, and culture. Our articles share all our ideas, reflections, and creative experiences. Stay Chill in a connected world. We wish you all a good read.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.