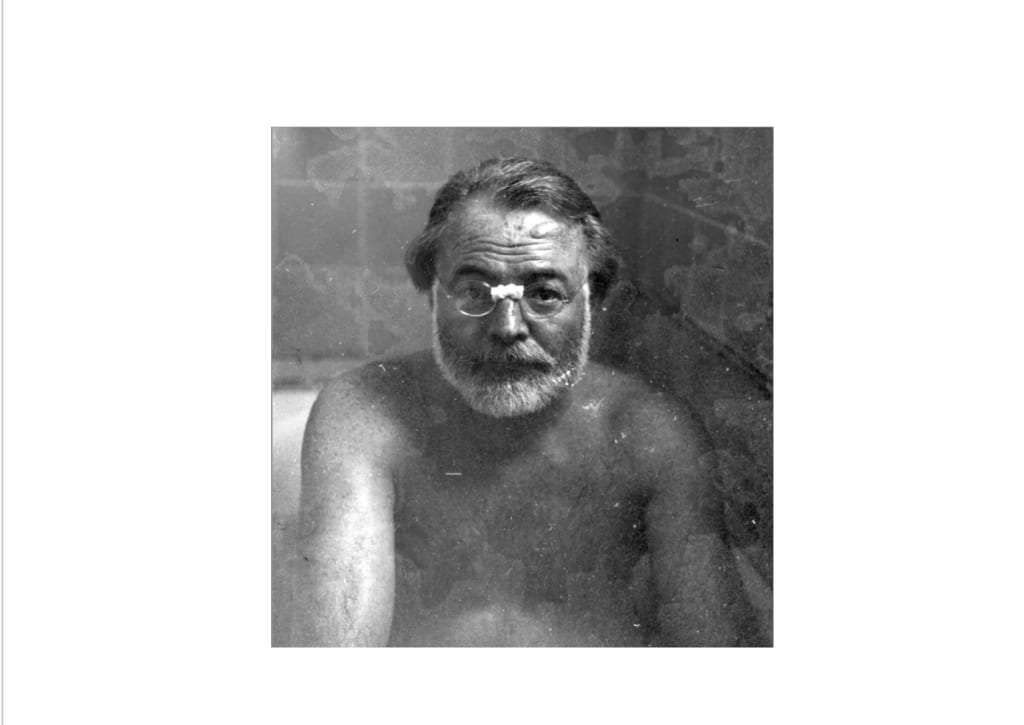

In Bed with Hemingway

Time to tell the story.

Everyone knows the adventurous American playboy who became the literary voice of the early nineteen-hundreds. But then again, everyone knows Coca-Cola, Barbie, and the iPhone; it’s no secret that the USA excels at turning its products into international icons.

Why wouldn’t the same apply to its writers?

Maybe it did, and Hemingway wasn’t actually that good, but just a commercial figure boosted by a brilliant marketing strategy.

Until you read The Old Man and the Sea and The Sun Also Rises. Then, you realise that his writing, after all, earned the Nobel.

It’s surprising how easily name-droppable Hemingway is, isn’t it? Say you’re having dinner with a group of people, and someone brings literature into the conversation, claiming they like Hemingway. They then turn to you and ask, “Do you like Hemingway?” You reply, “Well, yes.” “Nice! What’s your favourite book?” “The Old Man and the Sea.” “It’s great, right?” “Indeed!” And the truth is, you’ve never actually read it. Maybe the person asking hasn’t either. A perfectly plausible conversation — but I’m sure that wouldn’t work with Freud, Homer, or Marcel Proust — not even with Fitzgerald, for that matter.

We all kind of assume we’ve read Hemingway. Perhaps we read him in high school, years ago, or perhaps we simply feel as if we were born having already read him. I must confess, for years, I was among those who cheated themselves into believing they’d read him without ever actually doing so.

The day came when I finally decided to get to it. I bought The Old Man and the Sea, and voilà — what I thought would be the most outstanding book of all time left me puzzled. To be honest, it initially fell short of my expectations. How could this be the famous work? And so I decided to study the man and his writing until I understood why he is regarded as one of the greatest in history.

Just to give you a taste of it, let me begin at the end, the day that Papa Hemingway decided to take his life. It was a Sunday morning in Idaho. Ernest woke up at about 7 a.m., careful not to disturb Mary, who was sleeping upstairs in their bedroom. He quietly went to the basement, pulled out his favourite shotgun — a double-barreled Boss & Co. 12-gauge — placed the barrel of the gun in his mouth, and pulled the trigger.

By that time, he had written more than 80 articles and 18 books, at least four of which were major literary successes: The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls, and his final masterpiece, The Old Man and the Sea. He had already won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the Nobel Prize for Literature. He had four wives, three sons, and was friends with Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, Miró, and Picasso. He was known worldwide as a first-class fisherman and hunter. He had the boat of his dreams, Pilar, and a beautiful finca in Cuba. And above all, he loved what he did and did what he loved.

Why, then, would he kill himself? If I may briefly play psychologist here, I’d say the good old days were so good that the later ones felt hardly worth living. Picture Hemingway out with Pilar in the Gulf Stream, his friends aboard, beers are cold, and a thousand-pound marlin is fighting for its life while Hemingway, with all his strength, pumps and reels, pumps and reels. After five exhausting hours, the massive dark figure floats alongside the boat, nearly dead from exhaustion. Hemingway grabs a harpoon and finishes the deal. But by now, too much blood has spilt into the water; soon, the first shark arrives and takes a large bite from Hemingway’s catch. Another shark follows, crashing against the boat to tear another chunk from the marlin. Hemingway pulls out his shotgun, moves toward the edge of the boat and begins shooting at the sharks.

Afternoon arrives, and the boat anchors near a deserted beach lined with white sand and palm trees. The sea is calm, and the fish is no longer hooked to the boat; instead, it’s being prepared for lunch. Hemingway takes a nap while a fresh breeze keeps the heat away. Later, he wakes up and begins writing, capturing the scenes that, years later, would become The Old Man and the Sea.

For nearly twenty years, he lived like this — going out onto the water almost every day and writing tirelessly, reaching a level of productivity possible only when the man inside and the man outside are in perfect harmony.

Now picture the same man after two consecutive plane crashes, barely able to move or speak, confined to a concrete house in Idaho, subjected to electroconvulsive therapy for severe depression and paranoia — he believed the FBI was following him. A powerful body that once boxed, hunted lions, and fought bulls, was now weak, fragile, and in constant pain. No longer fishing, hunting, or even writing much, Hemingway saw his scarce work harshly criticised by the press. Inspiration had deserted him.

The literary style that made him famous — clear, decisive, and vigorous — was now dissolving into confusion and memory loss. Pilar floated alone, slowly rusting away. In the end, Hemingway found himself living precisely the life he had always feared — the life of quiet desperation. He was not to tolerate it, and so he did what he did; he placed the final full stop.

Hemingway changed the way the world writes. His sentences were short. His vocabulary, plain. His emotion, restrained. And yet, what lies beneath — the silence, the weight of what’s unsaid — often carries more power than any ornamented prose could. He called it the iceberg theory: only one-eighth of the meaning should show on the surface, while the rest remains hidden below. It came from his years as a reporter, where clarity and impact mattered more than anything. But it was also a worldview: that dignity lives in what isn’t said.

Today, in a world saturated with noise and self-expression, Hemingway’s stripped-down style feels urgent again. Writers across languages and cultures still borrow from his rhythm, his economy, his discipline. To write like Hemingway is not to write simply — but to write truthfully, without hiding behind words.

If you’re going to read Hemingway, here’s some advice. First, don’t worry too much about the language. At times, it can feel unfamiliar — he uses American slang, technical vocabulary (especially in his fishing or hunting stories), and occasionally words that are less common today. But that’s no reason to stop. Keep reading, even if you don’t understand everything. The rhythm will carry you, the story will land, and the deeper meaning will come with it.

The next thing to focus on is the simplicity of the language itself. His sentences are short, direct, and sometimes even awkward. Don’t let that put you off. That uneven rhythm is part of the honesty in his style. Hemingway didn’t write to embellish — he wrote to tell the truth, just as it is. But don’t mistake simplicity for simplicity of thought. Hemingway was no fool. So, read between the lines. Look for the feelings, reflections, and ideas folded beneath the concise prose.

As for where to begin, I’d suggest starting with a short piece written for Esquire, “On the Blue Water.” Then, reading a bit about his style in The New Yorker’s “Last Words.” Move on to The Old Man and the Sea, and after that, to The Sun Also Rises. Finally, for a portrait of the man himself, go back to The New Yorker for a brilliant profile: “How Do You Like It Now, Gentlemen?” No need to read more.

Who knows, maybe after reading all these, you’ll become a fan of Hemingway, just as I am.

About the Creator

Carlos M. Suárez Tavernier

📚 Philosopher - Aesthetics & Art

📖 Writer

I post intellectually entertaining articles + book reviews.

👀

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.