How to Write a Feature Film

Herzog kiboshes the 3 act structure

Werner Herzog says don’t use the 3 act structure. But he’s a genius. Most of us need to learn the ropes in order to untie them one day and let our particular genius fly. The ropes are the 3 act design.

Rule #1: You’re not Herzog.

As a rule, I don’t like rules. But many are there to help us and once we thoroughly understand their function we can break them.

The 3 Act Structure:

Act 1: Get your man up a tree.

Act 2: Throw rocks at him.

Act 3: Get him down.

So -

Act 1 is the set up: Get your woman up a tree.

Act 2 are the complications and obstacles: Throw rocks at her.

Act 3 is the denouement and the resolution: Get her down.

The Hook: Your opening scene should set the tone for your movie and bring plenty of intrigue so that viewers want to stay in their seats and keep watching. It can be a flashy object or a tasty morsel but it needs to accomplish its title. A good hook opening: The Shawshank Redemption.

Inciting Incident: This happens in act 1 and kicks the whole story into gear. It drives the entire movie and poses a question that must be answered by your protagonist in act 3. In Shawshank: Despite protesting his innocence Andy is found guilty and thrown into prison for life.

Shawshank is a sterling example of the 3 act design. Watch it (and many other movies) and pay attention to where the Inciting Incident occurs. It’s usually within the first 10 pages of the screenplay, so in the first 10 minutes of a movie (1 page generally equals 1 min of running time). But they’ve also been known to land at the 30 minute mark and anywhere in between.

When you watch a movie do a stop and start. Hit the pause button at the Inciting Incident and take note of where in the film’s timeline it happens. Five minutes? Fifteen minutes? Do this for all the major events of the movie (some are outlined below). This is its structure. Ask yourself: Why did the writer put it there? And not there? Would it have worked better elsewhere? Place these events on a timeline - draw one, they're easy: make a horizonal line, divide into acts 1,2 and 3, mark key scenes on the line. Do one for your own screenplay too.

Tip: Fight the war on cliché. Your best tool for the job is: Research.

Turning Points: These scenes will have more weight than other scenes as they’ll reveal a 180 degree turn. TP 1 comes at the end of act 1 and kicks us into act 2 - the same story, of course, but its off in a different direction. For Andy it's overhearing a certain conversation.

Act 2: This is the longest act and is often referred to as "Act 2 hell" when writing it. That’s because obstacles and complications have to make sense while upping the anti and moving the story forward. Your protagonist is out to achieve something and Act 2 throws every possible wrench into the works. This act is generally an hour long (60 pages) and contains a midpoint wherein your protagonist is in over her head. Perhaps she has made a huge commitment with severe consequences for turning back: that's why it is sometimes called the point of no return. It occurs around the act 2 halfway mark, so approximately 30 minutes into the act and 1 hour into the movie. Mark it on your timeline.

Crisis and Climax: Crisis means "decision". In a screenplay it is the point of greatest tension, as it is here that your protagonist will make the ultimate decision that either achieves their Object of Desire or loses it forever. This is the scene the audience has been waiting for since the Inciting Incident in Act 1, and it must contain a True Dilemma, which is: "the choice between irreconcilable goods, the lesser of two evils, or the two at once..."

A great example of a TD is Sophie’s Choice. When you're working on the dilemma, think about that choice Sophie had to make. Yours doesn't have to be that extreme but it's a good measure to keep in mind when creating a worthy crisis.

Both crisis and climax are nuanced and depend on many other aspects of your screenplay (as does everything else). Generally, they occur at the end of Act 2. But in some cases the climax spills over into the 3rd act - Casablanca has a 3rd act that is almost entirely made up of climactic actions.

(Aside: If your crisis moment veers to the positive, then the climax will be negative. And vice versa. So at approximately an hour and half into the movie, if the leads are so in love that there’s a montage of honeymoon happiness in Italy, then you can be sure one of them is biting the Venetian dust in the next scene, the climax.)

Tip: Write the essence of each of your scenes on index cards, one scene per card, stating its main event and purpose in the scheme of things. Mark the crucial scenes - Inciting Incident, TP 1, Midpoint - with colour markers or even different coloured index cards. Arrange them on an empty wall in rows that represent each act. They will function like a map and keep you from getting lost as the events of your story pile up. If I'm stuck before I even get to the wall I'll toss whatever cards I have into the air and see if they give me some revelation of sequence upon landing. This can be very effective.

Conclusion: Of course you will find exceptions to all the rules of the 3 Act design. Alfred Hitchcock, who often employed this structure, would violate at least one basic rule in each of his movies. Killing his protagonist off halfway through one of his flicks was unheard of and in North by Northwest his use of deus ex machina for the 3rd act climax was/is a strictly verboten act. You are strongly advised to not invoke deus ex machina in your screenplay.

Rule #2: You are not Hitchcock.

This is but a sampling of what to contemplate as you write. There's so much more to consider: genre, subplots, characters, conflict, etc. There are many good books on screenwriting and I’ve read them all. The best of the lot is Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee (that's his definition of True Dilemma that I use above).

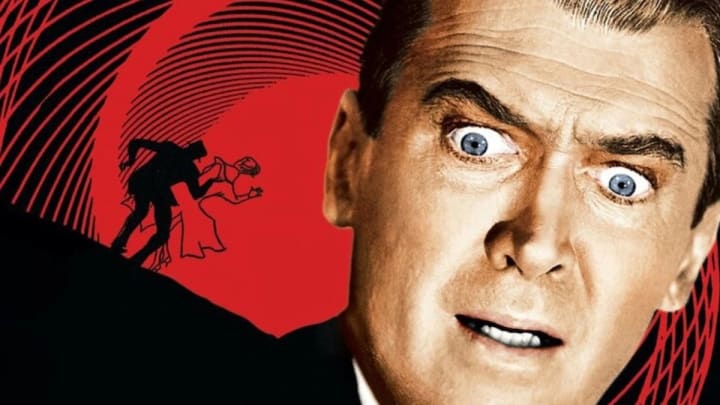

If you want to write a screenplay, read Story, reread it, make notes, refer back to its pages often. And, for the love of film, watch Herzog's movies (my faves are Nosferatu and The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser). Don't bother doing a stop and start, just sit back and enjoy.

Synopsis of one of my own screenplays:

Thanks for reading!

About the Creator

Marie Wilson

Harper Collins published my novel "The Gorgeous Girls". My feature film screenplay "Sideshow Bandit" has won several awards at film festivals. I have a new feature film screenplay called "A Girl Like I" and it's looking for a producer.

Comments (6)

It sounds easy but super hard the same time, to make this in a way that is actually going to work. I had no idea of many of these things, so thanks for explaining this all!

Lovely descriptive, fantastic advice and a great summary of the art. This approach to analysis of a story can also help drag a failing written story out of the Doldrums. I would also recommend taking a good look at the structure of The Lion King, the original animated 1994 Disney movie. The script was written after attendance at a Robert McKee script writing course, a course that I attended around the same time which is why I mention it. McKee used Casablanca as his model script.

Great and informative!! 💜

I love the practical tips, especially the index card map idea.

This was very informative and you communicated each step thoroughly. I am always looking to expand and define my skills so I will look into this further. Thank you Marie.

Glad I'm not the only Herzog fan here!