How to Poison with Mushrooms, Part 1: An Intro to Fungal Toxicology

I swear I'm a writer... and a med student

Since a character in a story I'm working on is a mushroom whisperer, a mage who can manipulate mushrooms, I've decided to embark on a little learning project, exploring these enigmatic organisms in greater depth so that I could develop my character's magic to a deeper level. And I'm not sure why, but this title popped up first in my head, probably because the Amanita mushroom toxin was recently mentioned in a molecular biology lecture, so I'm going with it.

Use this guide however you will, whether as a plot point in a story or to avoid poisoning yourself or your loved ones, only please avoid using it for the purpose mentioned in the title. Seriously. God is watching you.

Ok, now that you've been warned, look at this cute little delicious thing:

That's a chanterelle, my favourite edible mushroom, perhaps the only one I really like. Well, that most everyone likes.

And here's a jack-o'lantern.

I doubt that I would confuse the two, in part because the latter doesn't grow where I live and looks like what we Latvians call dog mushrooms (a colloquial term for unedible and thus useless fungi), while I've seen and eaten the former many times. Besides, interestingly, jack-o'lanterns glow in the dark. However, many do confuse them, and, while jack-o'lanterns may not be fatal, they are still toxic and cause gastrointestinal symptoms, like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Now look at this cutie:

Guys, that's a lamp. Don't eat anything, or anyone, that glows.

This one looks normal, though?

Nope.

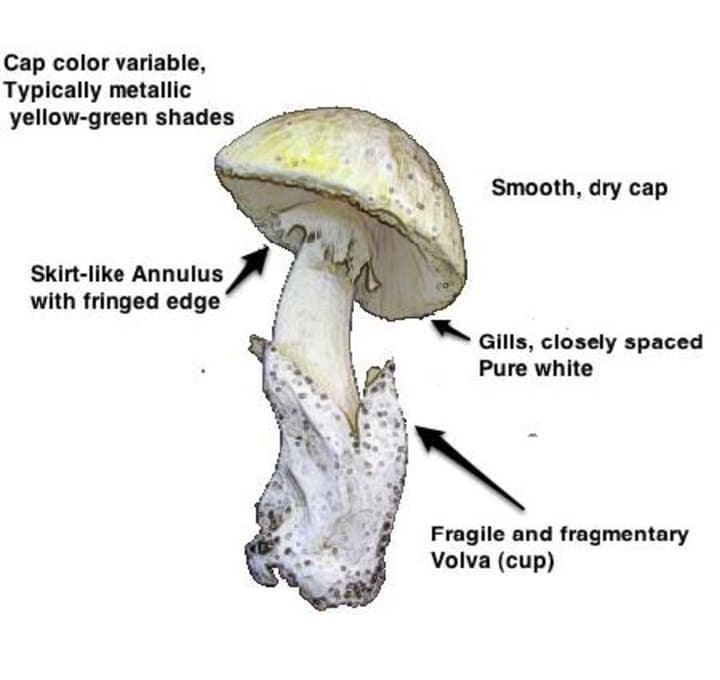

That, my friends, is the very angel of death, responsible for the majority of mushroom poisonings worldwide. Let me introduce you to

Death cap (Amanita phalloides)

This fungus is the deadliest known mushroom to humans, containing about 110 poisonous substances and responsible for the majority of mushroom poisonings worldwide, some of which prove to be fatal.

If you ever plan to gather wild mushrooms or poison a character of yours for that matter, you should be familiar with the morphology of poisonous mushrooms in your region (or that of your characters). Luckily, the Internet is full of such resources, for example, WikiHow has a whole guide dedicated to identifying death caps.

Death caps are native to Europe but have been introduced to all the other continents, except for Antarctica, along with imported trees, with which they form a symbiotic relationship (like many fungi do), taking the tree's carbohydrates while helping it absorb water and nutrients and resist disease in return. Due to this relationship, death caps typically grow near broadleaf trees like oaks, birches, and elms, while in the US, they are often found near pine trees.

See, the queen of death is not evil. Actually, she's quite collaborative. It's just that she's just not supposed to be eaten

If you do happen to eat a death cap (they're said to be delicious), abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea will show up 6 to 24 hours after ingestion, long enough that you may have forgotten that you'd eaten a mushroom. After a day, the symptoms will diminish, and you may feel fine for the next three to six days. Then symptoms of severe liver and kidney damage, such as yellow skin colour and seizures, will appear, and if you don't seek medical help ASAP, you will probably fall into a coma and die.

Why?

An Introduction to the Science of Mushroom Poisoning

Everyone knows that poisonous mushrooms exist. The question is, how and why did those poisons end up there, and what exactly makes them poisonous? Also why are some mushrooms poisonous to some species and not to others?

It is thought that toxins serve as a defence mechanism for poisonous fungi. While some mushrooms have a strong, pleasant smell to attract animals that would consume their spore-containing fruiting bodies and introduce them to a different place via feces, other species produce poisonous substances for the exact opposite purpose - to protect themselves from predators such as insects, slugs, or rodents and heighten their chances of successful reproduction.

The main mushroom toxins are

- cyclopeptides, the most severe of which are amatoxins (hepatotoxic),

- gyromitrin (metabolic, epileptogenic, as well as hepatotoxic, though to a lesser extent than amatoxins),

- orellanine (nephrotoxic),

- norleucine (nephrotoxic),

- psilocybin (neurotoxic),

- ibotenic acid and muscimol (neurotoxic),

- muscarine (neurotoxic).

The deadliest species are those containing cyclopeptides, causing 90-95% of mushroom-caused human fatalities. There are, of course, many other mushroom toxins that cause gastrointestinal or allergic symptoms of various levels, as well as ones that are dangerous in specific conditions, such as coprine, a substance produced by the inky cap (Coprinopsis atramentaria) that blocks acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (an enzyme that breaks down acetaldehyde, a metabolite of ethanol), which results in sickness if alcohol is ingested.

For now, let's return to our death cap.

How alpha-amanitin kills

A single bite of the death cap can kill an adult, no matter whether you boil, cook, freeze, or dry the mushroom before you eat it. How?

As it turns out, the death cap contains three main types of cyclopeptides: amatoxins, phallotoxins, and virotoxins. The early gastrointestinal symptoms are caused by phallotoxins, specifically phalloidin. The most dangerous toxin, though, is a particular amatoxin named α-amanitin, particularly abundant in the cap, gills, and ring in the earliest development stages of the fruiting body.

What α-amanitin does is inhibit RNA polymerase II, the enzyme responsible for the transcription of DNA into mRNA, which is in turn used as instructions for protein synthesis in ribosomes. Blocking this enzyme then stops the synthesis of proteins (including this one), which results in a deficit of proteins that are essential for structure, cell communication, and basically all functions that a cell performs. This, along with the amanitin-mediated formation of free radicals (which increases oxidative stress), ultimately leads to cell death. Once α-amanitin is absorbed in the digestive system, the first organ it meets and the one it impacts the most is the liver (though other organs, especially the kidneys, suffer, too), and the destruction of hepatocytes (liver cells) is the most lethal and least treatable aspect of death cap poisoning. There is no effective antidote and no single widely accepted set of guidelines, so the mortality rate is still high (10-30%). Treatment involves keeping the patient hydrated, electrolyte replacement, gastric decontamination, a combination of antibiotics, antioxidants, and other drugs for alleviating symptoms and treating complications, as well as liver transplantation in the case of its failure.

Four genes have been identified to code for alpha-amanitin in certain mushrooms. The reason the death cap is so dangerous is that it contains all four in dozens of copies, the consequence of which is lots of alpha-amanitin.

In case you're wondering how the death cap doesn't poison itself, the mushroom has a different RNA polymerase that is not affected by the toxin.

Other amanitin-containing mushrooms

Alpha-amanitin and other amatoxins are mainly found in certain species belonging to three genera: Amanita, Galerina, and Lepiota.

Amanita virosa (European destroying angel)

Amanita verna (fool's mushroom)

These three species of Amanita - A. phalloides, A. virosa, and A. verna - form the trio of the deadliest mushrooms of the whole world. Amanitins are found in other Amanita species as well, including two "death angels", namely A. ocreata (western North American destroying angel), A. bisporigera (eastern North American destroying angel).

Speaking of the other two amanitin-containing genera-

Waaait, turns out there is something worse than a death cap:

Galerina sulciceps

This "typical little brown mushroom" is mainly found in tropical Indonesia and India, as well as in European greenhouses on occasion, so that's why it does not cause the majority of fatalities worldwide and, as a consequence, is not as researched. Yet it contains α-, β-, and γ-amanitin in possibly higher levels than in the death cap. Due to this and the mushroom's too-typical looks, it may be perfect for a tropical poisoning trope - it may not be hard to persuade someone not particularly experienced with mushrooms that it's a, let's say, penny bun.

Another amatoxin-containing species from the Galerina genus is Galerina marginata (funeral bell, autumn skullcap), a mushroom found on stumps of conifers and occasionally broadleaf trees as well and widespread in the Northern Hemisphere (Europe, North America, and Asia).

By the way, I can't get over how dramatic English names for poisonous mushrooms are. Death cap, skullcap, plenty of death and destroying angels, funeral bell. Love it.

Amatoxins are also found in several Lepiota (parasol/dapperling) species like

Lepiota brunneoincarnata (deadly dapperling)

Lepiota brunneolilacea (star dapperling)

Lepiota subincarnata (fatal dapperling, deadly parasol)

Not every amatoxin-containing mushroom will cause the same symptoms, as the toxicity of a mushroom depends on the combination of toxins it contains. For example, many Lepiota species lack phallotoxins, which cause the gastrointestinal symptoms that appear in the first 24 hours after death cap poisoning, so they might not cause vomiting or diarrhea until later or only present with liver failure symptoms, which makes their poisoning even harder to identify at an earlier stage and thus more dangerous.

Why do people even eat these things???

The main cause of mushroom poisonings is incorrect identification of a mushroom, mostly by a newbie mushroom forager or someone new to the place who thinks they've found a snack they've learned to harvest in their native area. Many of those struck by the death cap think that what they've eaten were meadow mushrooms (Agaricus campestris) or paddy straw mushrooms (Volvariella volvacea). This is why you should never forage for anything about which you're not 100% sure that you could tell it apart from any other mushroom that may grow in the area. The problem with death caps, though, is that they are quite invasive, so, as they spread to yet new places, people may not even have the slightest idea that these may be found where they live. It doesn't help that these mushrooms are most poisonous in the early stages of their development when they might resemble other species the most.

Another thing to keep in mind is children and pets, who could eat any random stuff in your yard if it caught their attention. And then there are the kind of shroomie guys that intentionally consume a poisonous mushroom with the intent of having a psychedelic experience.

How to treat amanitin poisoning in ❗ fiction ❗

For the people in the back, please do not attempt to medicate yourself in a life- or health-threatening situation, unless you're on an uninhabited island or something, that is. If you have the slightest reasonable suspicion that you might have ingested something poisonous, contact a healthcare provider. In my country, for example, you can call a special toxicology info center at any hour. I know it's a cliché, but it's always better to be safe than sorry.

Ok, now that we've cleared this up, in case your character does find themselves on that uninhabited island or if they live in a medieval fantasy setting or in any circumstances where advanced healthcare is not accessible, here's something that you could use besides activated charcoal:

Seed of the milk thistle (Silybum marianum)

The milk thistle has been used since the times of classical Greece to treat liver and gallbladder disease and has been found to have cytoprotective and anticarcinogenic properties. What is even more interesting is that it is used even nowadays as a supportive treatment for death cap poisoning. Due to how the active ingredient of the plant, silymarin, found mostly in the seeds, is processed in the digestive tract, it ends up in higher concentrations in the liver than in the blood. When taken orally or intravenously, a derivative of this substance, silibinin, inhibits the entry of amanitin into liver cells by outcompeting the toxin. This prevents liver injury and gives time for the kidneys to filter the toxin out.

Milk thistle is quite safe, aside from mild gastrointestinal distress and allergic reactions, side effects are rare. The problem, though, is that there's not enough data to conclude how effective exactly the drug is: although it seems to reduce mortality, it is always used in combination with other medicines and more as a last resort; besides, the research on this treatment has not exactly involved crowds of people for obvious reasons. However, this plant does heighten the poisoned patient's chances of survival.

If you decide to use this plant in your writing, make sure that it grows in the area where the story takes place.

Possible future remedy - a dye???

Several potential antidotes have been identified that still have to be fully tested and developed, so you may use them or even something more sci-fi in a more futuristic story.

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a fluorescent dye widely used in diagnostic procedures such as ocular angiography (visualization of blood vessels in the eyes), measuring cardiac output, and assessing liver function. ICG has been found to inhibit STT3B, a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of N-glycans, which are proteins involved in the entry of various agents, such as viruses and bacterial toxins, as well as alpha-amanitin, into cells. The binding of amanitin to these proteins makes it easier for it to get inside its victim's cells, so scientists have hypothesized that blocking the N-glycans of amanitin transporters using ICG would keep amanitin from being recognized as a toxin and taken into liver cells. Experiments on mice seem to confirm that ICG can prevent amanitin-induced cell death and immune cell infiltration. Upon injection, the dye mostly ends up in the liver (though it helps the kidneys, too), where it is easily cleared, causing no obvious side effects, which makes it an amazing potential antidote for amanitin poisoning.

Final thoughts

This guide, which I've decided to break down into a series, is meant as an introduction to mushroom toxicology, not as an exhaustive list of deadly mushrooms. To protect yourself or your characters, you will probably still need to do some story-specific research on your own.

A few tips for mushroom enthusiasts and foragers: Never pick up a mushroom that you don't know well. Do a search on Google or flip through the pages of a book on mushroom foraging to get acquainted with the poisonous mushrooms in your region and learn to distinguish between edible mushrooms and similar poisonous ones. Again, never eat something, unless you are 100% sure that it is edible (and you're well-informed enough to make such a decision).

A few tips for writers: In a fantasy setting, you can invent your own mushrooms. If your story takes place in the real world, I recommend looking into the poisonous fungi of that specific region, taking note of their characteristics and effects, as well as, depending on your needs, the biotopes they grow in (like the trees they form mycorrhizal relationships with) and the season when their fruiting bodies appear. Hopefully, this article (and the next ones in the series) gives you inspiration for your story.

***

In the next article in this series, we're going to continue hunting for poisonous mushrooms, taking a look at the next toxins on the list, gyromitrin and orellanine. While I nerd over poisonous mushrooms so you don't have to, stay away from poison!

Sources/read more:

- https://www.britannica.com/science/death-cap

- https://www.inrae.fr/en/news/what-origin-deadly-toxins-mushrooms

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/167398-overview?form=fpf

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26375431/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0041010118307281?via%3Dihub

- http://www.bccdc.ca/health-info/prevention-public-health/death-cap-mushrooms

- https://www.health.act.gov.au/about-our-health-system/population-health/death-cap-mushrooms

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/567964/

- http://www.amanitaceae.org/

- https://www.webmd.com/first-aid/death-angel-mushrooms

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6348736/

- https://www.latvijasdaba.lv/senes

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/156994/

- https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2005/1001/p1285.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5657817/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-37714-3

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1008902-treatment#d8

About the Creator

Jūlija B.

Hey, I'm a multipassionate med student self-studying languages & linguistics and a math tutor trying to find time for music and writing, which I use as an excuse to explore anything that captivates my heart. https://buymeacoffee.com/julijab

Comments (4)

Impressive!!!

I've always been fascinated by the dual nature of fungi—capable of healing or harming depending on the hands that wield them. Delving deeper into this world, I sought out reliable sources that offer both education and quality cultivation options. That’s how I came across b+ mushrooms https://fungiape.com/b-plus-mushrooms/ a resource that provided me with premium spores and essential guidance for responsible use. Through their offerings, I gained access to expertly curated strains, ensuring both safety and an enriching exploration of fungal properties.

welll done👌

Thank you for your interesting and exciting stories. Follow my stories now.