Broken Arms and Borrowed Tunes

Funnel of forgotten Octobers

There's a cardboard box in my mother's attic that nobody wants to open. You know the kind, yellowed tape, your childhood handwriting scrawled across the side in marker that's now the color of rust. I opened it last Tuesday.

Inside, buried beneath report cards and elementary school art projects, I found three things that made me sit down right there on the dusty floor: an armless doll, a metal funnel, and my grandmother's songbook.

The doll came first. She'd been beautiful once, porcelain face, hand-painted lips. I'd named her Clara. But somewhere between age seven and eight, both her arms had snapped off. Most kids would've thrown her away. I didn't. I kept her in my backpack for an entire year, convinced she needed me more because she was broken.

Isn't that what we do? Hold onto the damaged things, the imperfect pieces, because throwing them away feels like admitting defeat.

The funnel was my dad's. He'd used it every autumn when he'd make his terrible homemade cider, the kind that was more vinegar than apple. He'd stand at the kitchen counter, cursing under his breath as he tried to pour the mixture into recycled wine bottles. That funnel was the only thing that made the job possible. After he died, I'd stolen it from the garage. Not because I'd ever make cider. Because it smelled like October and optimism and my father's stubborn refusal to quit things he was objectively terrible at.

Then there was the songbook, with cream-colored pages, corners soft from being turned a thousand times. My grandmother had taught herself piano at sixty-three using this exact book. "It's never too late," she'd told me, her arthritic fingers stumbling through "Moon River" for the hundredth time. "You just need to want it bad enough."

She never did get very good. But she played anyway.

I sat there with these three objects in my lap, and suddenly I understood something I'd been too young to grasp before. We don't keep things because they're perfect or useful or valuable. We keep them because they're proof. Proof that we loved someone. Proof that we tried. Proof that broken doesn't always mean worthless.

Clara, the armless doll, taught me that being incomplete doesn't disqualify you from being cherished. Dad's dented funnel reminded me that passion matters more than skill. And grandma's songbook? That was a middle finger to every voice that whispers "too late, too old, too damaged."

I took all three things home with me. They're on my bookshelf now, between novels I haven't read and photographs I keep meaning to frame. When people ask about them, I just smile.

Because how do you explain that a broken doll, a kitchen tool, and sheet music for songs nobody plays anymore are actually instructions for living?

You hold onto what matters. You find beauty in the imperfect. And you never, ever stop trying.

Even when you've lost your arms along the way.

About the Creator

Diane Foster

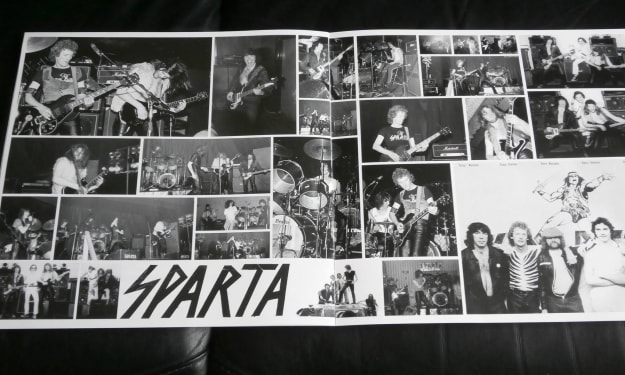

I’m a professional writer, proofreader, and all-round online entrepreneur, UK. I’m married to a rock star who had his long-awaited liver transplant in August 2025.

When not working, you’ll find me with a glass of wine, immersed in poetry.

Comments (2)

Never give up! Never surrender’! Great work

Instructions for living—describing those items in that way gave me chills. An absolutely stunning and beautifully, reverently nostalgic piece.