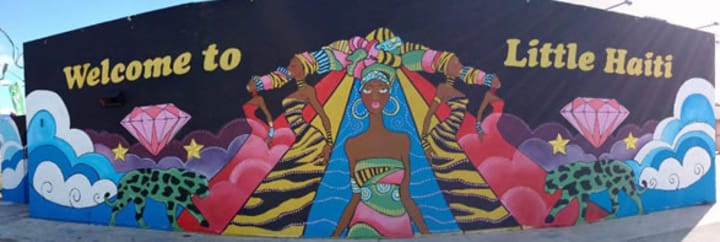

Welcome to Little Haiti, Miami

Where My Roots Are Deeply Buried

Living in New York was always where I wanted to be—with its skyscrapers, shopping and nonstop activities. However, much of the time, there’s nowhere I would rather be than right back home again. Enjoying the pristine, white sand beaches and Miami’s tropical weather. At least, that is the part that everyone recognizes. For myself, however, Little Haiti, which is also located in Miami, is much more than that.

As I drove into the block, I was suddenly hit with nostalgia. A memory of our maternal grandmother, who lived a block away, and would walk to our home to help cook and clean came to me. An old Cuban man riding a trike with a large stereo tied to it blaring Celia Cruz was catcalling my grandmother who was on her way. We heard my grandmother calling us to open the door. She quickly came inside and shut the door. The Cuban man rode his tricycle in our yard and was calling my grandmother to come out, “Mami, por favor, te amo!” (“Mami, please! I love you!”) We all laughed.

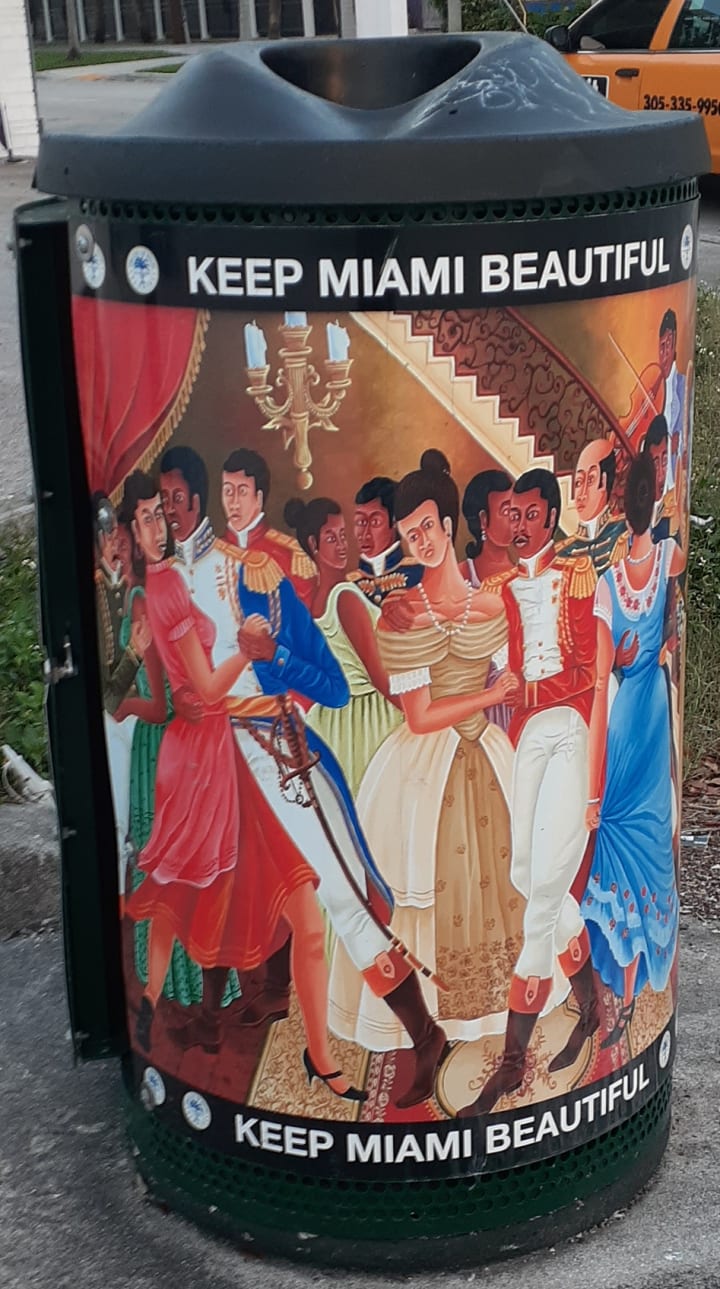

When venturing home, my favorite place to visit is still the same. Once I have had a chance to see my family again, I cannot stay away from the Mache Ayisyen (Haitian market). It is a modern replica of the iron market in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. As soon as you arrive, the highly decorative fretwork and flamboyant colors greet you. Many Haitians- visiting or living there- are hit with a wave of nostalgia when they see it. My mother says she feels she is truly at home here—a world that I haven’t had the chance to see yet.

The tin rooftops and architectural lattice work only serve to enhance the look and feel of home within the space. And right beside the market is the Little Haiti Cultural Complex where, prior to the pandemic, I could experience the true culture of Haiti and of my ancestors. In fact, it was the place where I took lessons in everything, from art to dance and music. Where I, alongside my siblings and classmates, learned about the country that our parents came from. It was here that I learned to honor and appreciate the rich, unique history of Haiti. But things have changed from those days. (The following video was made by Miami and the Beaches)

In fact, today, my hometown is changing in many ways. White and Latina families are moving in, while Haitian families are moving out. Chickens and roosters still scavenge for food in the backyards of our neighbors. New businesses are opening at every turn. Yoga centers, restaurants, cafes, gyms and more are erected where empty buildings, lots, and gardens once stood.

For those who have never been there, Little Haiti is a neighborhood in Miami that is predominately Haitian. In fact, it’s one of the first stops in America for those who have fled Papa Doc’s cold-blooded regime. The area that has now become Little Haiti was my parents' first stop when they fled Haiti as newlyweds in 1969 and the place that they were able to continue building their lives. Two years later, they saved enough money to purchase their first home.

My parents moved into an all-white area in Miami called Lemon City. One day, as my father walked around the neighborhood, a white man angrily approached him asking him what he was doing there. My father did not speak English and once he realized this, the man’s demeanor changed. He asked, “Do you speak French?”

“Oui!” Yes! my father responded.

The man smiled and said, “Oh, you’re a Frenchie!” He turned around and gave a motion telling the neighbors to stand down. My father looked around and saw gun nozzles being withdrawn from windows. He was very shocked. The man attempted to speak French and walked around the neighborhood with him.

At that moment, my father realized that it had only been three years since Martin Luther King, a black man whom he always saw in the newspapers, was assassinated. He knew that Black Americans were fighting for something, but wasn’t aware of the racism and injustices that were taking place. He wasn’t aware that he moved into a segregated neighborhood in the South. It confused him because when white Americans visited the Caribbean, they were always friendly. This man, who angrily approached him because he thought my father was African-American, was now treating him, a black man, as a friend.

It was the first episode of changes in our new neighborhood, but not the last. Still, over time, our neighborhood grew more diverse and then White families started to leave. In their place were even more Haitian families who fled from Haiti and were looking for a new, safe home for their families. I remember waking up in the middle of the night seeing two white eyes staring at me. I screamed and jumped off the bed. My parents rushed to my room and turned on the lights. The girl lifted her head and looked at me. “Who is that?” I pointed.

“Oh, that’s your cousin from Haiti!” I was told to hug her and go back to sleep. We hugged and laid back down staring at each other until we fell both asleep.

In a matter of a few years, the neighborhood became predominantly black. And Haitian. The once quiet neighborhood became vibrant with vodou drums beating on Friday nights, Compas music blaring from stereos on Saturdays, chansonnette Française, French love songs on Sundays, and dominoes slamming on tabletops every night.

Our community fell into a predictable routine. I would wake up every Saturday morning to a newly arrived cousin laying in my bed staring at me. I would also be found running errands and going to the flea market. The boys would be running and playing in the streets while the girls helped their mothers indoors, cleaning, cooking, washing and ironing. It was simple but easy to love and enjoy. It was the way of life for us, and it was one that we thrived on.

I felt safe in my neighborhood until, one day, my brother’s bike was stolen from our backyard. Days later, as we came to accept the terms of someone breaching our secure home, we watched a boy carrying a bike on his back with his mother walking behind him and holding a belt in her hand. We wondered why the boy carried the bike instead of riding it. As they approached closer, we recognized it was Ricardo’s bike. The mother stated that she was a single mother and was trying to raise her son to do the right thing. She explained that she was not raising a thief so she made him return the bike. The boy put the bike down and apologized to my brother for stealing it. My parents thanked her and told her she was doing a great job as a mother. My father then gave her money to purchase a bike for her son and a little extra for herself. She didn’t want to accept it, but he insisted and she finally did. She thanked him and we never saw them again.

Growing up, my life consisted of what is now known among Haitians as the 3 L’s. Lekol, legliz, lakay. School, church, and home. I wasn’t allowed to participate in anything after school nor have friends outside of the church environment. Every moment of the day was meant to be spent in progress. Whether in progress through education, through church or at home, it did not matter. It was about working hard and achieving your best, at all times. And education was not the only important thing. Behavior and respect were also essential. It was pointless getting all A’s if my grade for conduct was lower. Respect was to be shown at all times and there was no excuse for forsaking it. In fact, respect was ingrained in our culture all the way through.

Our backyard was not simply full of green grasses for children to play on. In fact, you might be hard-pressed to find a space that wasn’t filled with a vibrant array of herbs and spices. Whether you needed the perfect spice to round out a dinner or the right herb to heal an illness, it could be found right there. Among others, there is the sweet smelling lemongrass for fevers; soothing aloe for burns; wormwood and castor oil plant to get rid of parasites; sharp ginger root for some of our favorite dishes. The smells of everything from parsley and rosemary to chamomile, dill and thyme were our constant companions, wafting not only through our yard, but through the house on every breeze.

Edging between the herbs and spices were the trees. Big, beautiful trees that grew as we all did. Eight trees, one for each of the children in my family, literally grew as a part of us, from the dried umbilical cords that fell from each of us when we were infants. My mother planted our umbilical cords with the seeds. The trees, even today, continue to bloom and grow year after year, but even these trees are not merely ornamental or solely used for shelter from the hot sun. They also provide food for our family.

From the avocado tree that represents my brother Evens, to the Francis mango that represents Stanley, the Haden mango for Ricardo, breadfruit for Giselle, Tommy Atkins for Emmanuel, plantain for Nixon, and coconut for Fabienne, and not to mention the sugar apple for me. Each tree has its own sweet smells and sweet fruits to nourish our families. The juicy fruits are perfect after a long day in the hot sun. Lemon and orange trees used to accompany the ones that are still there, but the state cut them down.

Our neighborhood is now considered ‘up and coming’ and the prices of real estate in the area prove it. In fact, my father was recently offered almost a million dollars for his home, but my mother refused to sell. “We’re not going anywhere!” my mother said. “All of our children’s umbilical cords are planted deep in the roots in our backyard!” She made us promise to never sell our childhood home. It is that important to her, and to our legacy, that we continue to stay here and it is something that we have ensured.

The Little Haiti Cultural Complex and the Caribbean Market, the two places I love most to go when I return to Little Haiti, will continue to stand strong, no matter what other gentrification may happen in our community. They will continue to serve as a symbol for those who have moved to this area seeking refuge and better futures for themselves and their children. And they will continue to be beacons of everything there is to know about Haitian culture, both the part that came with our parents from Haiti and the part that we continue to build for ourselves, right here.

My hometown is who I am. It is who my community and my family are. It is the culture that my parents brought here with them and the traditions that they put down in our home. My foundation, my roots, are deeply buried in this community, both figuratively and literally, in my parents backyard.

About the Creator

Queenie Reigns

Mom of 1. Retired Homeschooler. Educator. Housekeeper. Head Chef. Dishwasher. Bookkeeper. I have always wanted to write, but my then husband discouraged me. We are no longer together. Just getting back to my passion.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.