What is BPD?

An Insight Into Borderline Personality Disorder (from a fellow sufferer)

What is a Personality Disorder?

A personality disorder affects how someone sees, thinks, feels or relates to others; having a personality disorder means that you experience things much differently to how the average person experiences things. A person with no known mental health disorder/illness is known as a neurotypical person, as they have no neurological problems that affect their thinking, feelings or their perception. The most common features of a personality disorder are as follows:

- Being overwhelmed by negative feelings such as anxiety, distress, anger or worthlessness

- Avoiding other people and feeling empty and emotionally disconnected

- Difficulty managing negative feelings without self-harming or, in rare cases, threatening other people

- Odd behaviour

- Difficulty maintaining stable and close relationships, especially with partners, children and professional carers

- Sometimes, periods of losing contact with reality

These symptoms typically get worse with stress.

Personality disorders often reveal themselves during adolescence and continue into adulthood and are often caused by traumatic events during childhood or genetic factors – mostly a mix of both. To differentiate between the different types of personality disorders, they are grouped into three categories: Cluster A, Cluster B and Cluster C.

People with Cluster A personality disorders tend to have difficulty relating to others and usually shows patterns of behaviour most people would see as odd and eccentric. Others may describe them as living in a fantasy world of their own. An example is paranoid personality disorder, where the person is extremely distrustful and suspicious.

People with Cluster B personality disorders struggle to regulate their feelings and often swings between positive and negative views of others. This can lead to patterns of behaviour others describe as dramatic, unpredictable and disturbing. An example is borderline personality disorder, where the person is emotionally unstable, has impulses to self-harm, and has intense and unstable relationships with others.

People with Cluster C personality disorders struggle with persistent and overwhelming feelings of fear and anxiety. They may show patterns of behaviour most people would regard as antisocial and withdrawn. An example is avoidant personality disorder, where the person appears painfully shy, socially inhibited, feels inadequate and is extremely sensitive to rejection. The person may want to be close to others, but lacks confidence to form a close relationship.

Personality disorders are quite common; in England 1 in 20 people suffer from a personality disorder. A lot of people recover from personality disorders over time and with adequate treatment. If the symptoms are mild to moderate, psychotherapy can be the best course of action. Different types of psychological therapies have been shown to help people recover from personality disorders. However, there is no single approach that suits everyone and treatment should be tailored to the person. Not all talking therapies are effective for everyone and it is essential they are delivered by a trained therapist to get the full benefit of the therapy, and make sure it is delivered correctly.

What is BPD?

Borderline Personality Disorder (more commonly known as BPD) is a disorder of mood and is the most recognised personality disorder.

The main symptoms of BPD can be grouped into four categories: Emotional instability (the psychological term for this is affective dysregulation), disturbed patterns of thinking, impulsive behaviour, and intense yet unstable relationships. These symptoms may range from mild to severe, but they usually emerge during adolescence and then they persist into adulthood.

The cause of BPD is unclear, but, like most conditions, it seems to stem from a mixture of genetic and environmental factors. Traumatic events experienced during childhood are associated with developing BPD; many people with BPD will have experienced childhood neglect, or any range of physical, sexual or emotional abuse during their childhood.

If you find you are experiencing any symptoms of BPD, the first port of call is to contact your GP who will likely ask about how you’re feeling, what your recent behaviour is like and what sort of impact your symptoms have had on your life to rule out any other diagnosis’ such as depression, but also to make sure there’s no immediate danger to your health and wellbeing, as if you are acting very impulsively, you may need to be treated sooner to stop any harm coming to you.

BPD cannot be cured; it is a disorder you will have for life. However, it can be treated through a combination of psychological and medical treatments to a point where you no longer suffer any symptoms, but relapses can happen. Treatment may involve going to therapy under supervision form the community mental health team (CMHT), or maybe taking medications that may help with some of the symptoms. Effective treatment can last over a year – some dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) courses can last up to 18 months for effective treatment. Over time, a lot of people can overcome their symptoms and recover, but additional treatment is recommended for anyone whose symptoms return.

People with BPD often have other mental health problems, such as: misusing drugs and alcohol, generalised anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, eating disorders, or another personality disorder. This is just a short list of the most common comorbid (co-occurring) conditions associated with BPD. BPD can be a serious condition just on its own, causing many people to self-harm or attempt suicide, but all these conditions can make the BPD symptoms worse, or present their own challenges to be dealt with on top of the BPD.

Emotional Instability

BPD comes with a range of intense, often negative, emotions. This means when you feel those emotions, they can feel ten times as strong as a neurotypical person’s emotions. The most common emotions to feel intensely are:

- Sorrow

- Shame

- Anger

- Panic

- Terror

- Love

There is also often long-term feelings of emptiness and loneliness. Most doctors will not recognise love as being one of the emotions that BPD sufferers feel intensely, due to the unstable relationships BPD causes and the tendency to cut people off on a whim, but most sufferers of BPD will admit that they feel love intensely too.

Mood swings are also common with BPD. It is normal to feel suicidal with despair and then, within half an hour to a few hours, feel happy or reasonably positive later. Some sufferers of BPD can feel better in the morning and then have a mood drop in the evenings, where others find their mood swings unpredictable. Extreme mood swings can become all-encompassing, which then turns into what is known as “splitting” but this term isn’t on the list of symptoms provided to you by a GP or a psychiatrist. Splitting will be looked at in more depth later on, as most sufferers of BPD will have experienced splitting, but will not have a way to describe it.

There are many treatments that will help with emotional regulation, such as medication and certain types of therapies. A few things that are suggested are:

- Mindfulness activities

- Identifying and Understanding Emotions

- “Check the Facts” - understanding valid emotions and how to act

- Opposite action – if your emotion isn’t valid, how do you act?

- Self-soothe/self-care

- Journaling

- Emotion diaries

There is also a BPD specific therapy: Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT). This works to “reprogram” or retrain your brain so your thought processes and emotional responses can mimic a neurotypical brain and help you regulate your emotions.

Disturbed Patterns of Thinking

Different thought processes can affect sufferers of BPD. There are three main types: upsetting thoughts, brief episodes of strange experiences, and prolonged episodes of abnormal experiences. These are all signs that the sufferer is getting more unwell.

Upsetting thoughts

Upsetting thoughts can manifest in many different ways. You may think things such as you are a terrible person or you may feel that you don’t exist. These thoughts and feelings may seem very real to you and you might be unsure if they’re actually true or not. You may seek reassurance from others around you that these thoughts and feelings are untrue.

Brief experiences of strange experiences

This is hearing voices outside your head for short periods of time (such as a few minutes, or a few words every now and again). These may feel like instructions to harm yourself or others around you, and you may or may not be sure whether these are real. The “voices” may sound like people you know, or may seem terrifying to you; it varies from person to person.

These beliefs are a sign that you’re becoming more unwell, and may be psychotic. If the beliefs are frequent and dangerous, it is time to get help. You can call a therapist, a helpline, or attend your nearest Urgent Care/Emergency Room, depending on the severity, type of hallucination/belief and how bad your mental state is because of this.

Impulsive Behaviour

With BPD, there are two types of impulses to control: an impulse to self-harm, and risky behaviour.

An impulse to self-harm

Self-harming doesn’t just refer to cutting body parts (most commonly the wrist); it refers to any behaviour that intends to do yourself harm. This means hitting yourself, pinching yourself, punching yourself, pulling your harm out, burning yourself, anything that is done with the intent to physically harm yourself. This is common amongst people suffering from BPD as you quite often feel an excess or a lack of pain. Self-harming gives you a way of controlling the pain or feeling pain again. However, this is an unhealthy coping mechanism, and can eventually lead you to attempt or succeed in committing suicide. If you, or someone you know with BPD, is feeling suicidal or attempting to committing suicide, please immediately ring the emergency services to get help.

An impulse to engage in risky behaviour

People with BPD commonly engage in risky behaviour because addiction or adrenaline can cause a brief sense of calm or happiness within yourself. Risky behaviours are in behaviour that gives pleasure but could have disastrous consequences, such as: gambling excessively, shopping sprees when you have little to no money spare, binge drinking/eating, doing excessive amounts of drugs, any form of addiction, and having lots of unprotected sex – especially with strangers. All of these activities can cause financial harm and serious health conditions but do not cause direct harm, so are not classed as self-harm. If you are struggling with any of these issues, please reach out to a support group or someone close to you.

Unstable relationships

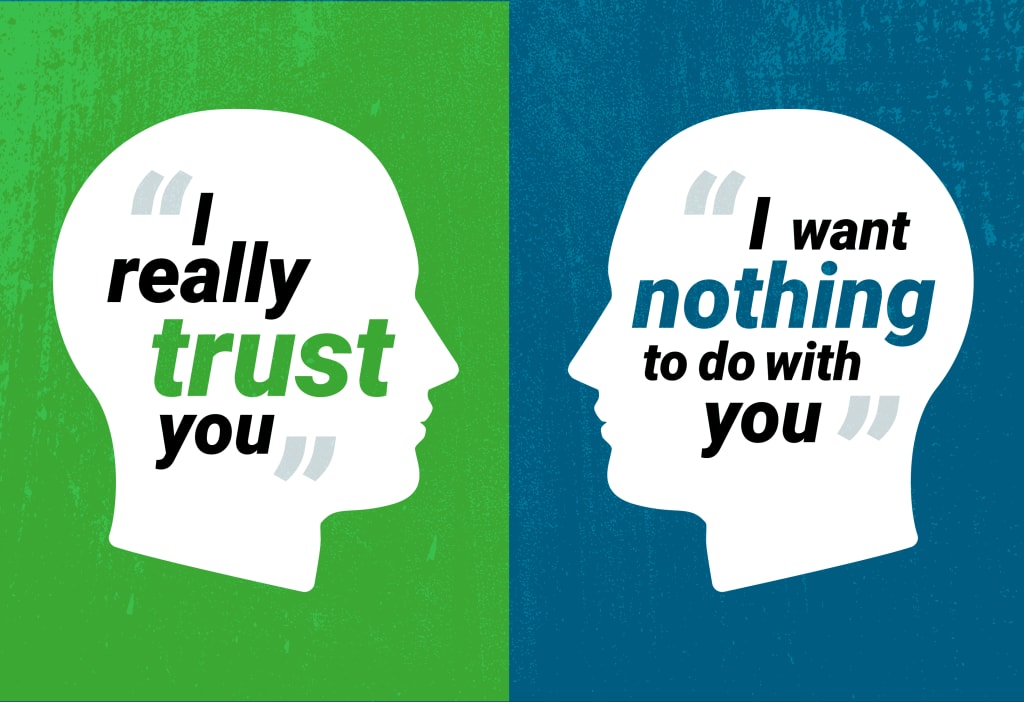

The final symptom is unstable relationships. Most people who suffer from BPD have black/white thinking - when applied to relationships, it comes across as "I hate you! Please don't leave me!". This logic applies to ANY sort of relationship: friend, family, carer, teacher, partner, work colleague, anyone you can get close to. Either a relationship is perfect and that person is wonderful, or the relationship is doomed and that person is terrible. People with BPD seem unable or unwilling to accept any sort of "grey area" in their personal life and relationships.

If you have BPD, you may feel that other people abandon you when you most need them, or that they get too close and smother you. When people fear abandonment, it can lead to feelings of intense anxiety and anger. You may make frantic efforts to prevent being left alone, such as:

- constantly texting or phoning a person

- suddenly calling that person in the middle of the night

- physically clinging on to that person and refusing to let go

- making threats to harm or kill yourself if that person ever leaves you

Alternatively, you may feel others are smothering, controlling or crowding you, which also provokes intense fear and anger. You may then respond by acting in ways to make people go away, such as emotionally withdrawing, rejecting them or using verbal abuse. These 2 patterns may result in an unstable "love-hate" relationship with certain people.

For many people with BPD, emotional relationships (including relationships with professional carers) involve "go away/please don't go" states of mind, which is confusing for them and their partners. Sadly, this can often lead to break-ups.

This is a brief summary of BPD, focused on the symptoms of the personality disorder. I hope this helps many people understand what is actually going on inside someone's head, or even their own, if they have Borderline Personality Disorder.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.