The Cognitive Neuroscience of Language, Timing, Rhythm and Music

A Founder’s Theory (Andrew Reid of Online Super Tutors)

In this article, I would like to share my ideas about music and memory, which I wrote about (much to the chagrin of my Uni professor!) for my final dissertation when studying Linguistics and AI and Sussex University in 2004. It turned out alright in the end...(apologies for the footnotes - they could not be edited properly - but, you'll work it out :))

It's a bit of a heavy read so if you prefer a video summary:

Or for the Deep Dive Podcast discussion, the audio can be found on this page:

Introduction:

In this paper I seek to find evidence suggesting that (harnessing of) timing mechanisms are fundamentally responsible for an efficient and economical method of sequential processing, and that this neurocognitive variable will have ‘transcribed’ itself into language. Sequential processing is of a multidimensional nature, consisting of serial, temporal and abstract dimensions (Dominey, et al., 2002:208). While all of these dimensions have a role in language, the temporal is of explicit interest as there are many forms of language (i.e. verse/musical forms) which use the (constraints of the) temporal in particular to manipulate the other dimensions to enhance the mnemonic effect of linguistic sequences. I propose that linguistic forms, which obey the ‘rules’ of the cycle of timing, are easier to encode and recall in memory.

Commitment to memory involves using working memory and phonological loops and an insight into these aspects is necessary. It is also presumed that language is an instrument, which is perceived like a real musical instrument, and that the forms of music and verse are ‘beautiful’ and memorable to us, because they obey template based rules of regularity whilst conforming to the constraints of temporal processing in the brain. I put forward that the neurological antecedents of language processing may be closely related to that of the processing of music.

The motivation for this research stems from my reductionist nature and a personal desire for unification of theory. Cognitive linguistics views language as emergent behaviour, which stems from more general aspects of cognition. These aspects must be underpinned by neural universals, as the anatomical uniformity of the brain gives good reason to believe that the same basic architecture supports all perceptual, cognitive and motor functions. There is a transcription from behaviour to cognition to (neuro) biology which is what is being investigated, and thus certain antecedents can be identified. Bearing in mind that the universe operates within precisely timed cyclic or rhythmic patterns, which are economical and (mostly) in equilibrium1, it can be inferred, and indeed observed, that living things also obey some rules of regularity within cycles.

In fact:

“Rhythm is one of the most pervasive aspects of the human condition; it is in the world around us and the world within us, in our bodies and our minds, our living and our thinking” (Auer et al., 1999: 5)

The mind uses mechanisms of timing throughout cognition - neural timing mechanisms being the naturally occurring phenomenon which controls the cyclic processing in living things with central nervous systems. These forms of natural timing allow the human brain to plan and sequence thought and action (motor and non-motor skill based), recognise patterns in its environment and perform complex problem solving activities such as social behaviour, dealing with language and other academia.

Dealing with language is a sequential procedure, operating uni-directionally, much like our conceptualisation/experience of time. Sequential cognition encompasses the capabilities to utilize and extract the sequential structure of perceptual and motor events in the world in an adaptive and pragmatic manner (Dominey et al., 2002:207). The spoken word itself is, essentially, the product of a motor skill involving the apparatus of speech2, and thus rhythm and its relation to neural based timing of language is best observed in this form and its interpretation by the hearer, as opposed to orthographic forms of language.

In light of this, and in respect of research based on perception, timing, and discourse conducted by Ernst Poppel, Wallace Chafe, and Vyvyan Evans, arrangements of units of language (in metered form) shall be studied, considering the relevant temporal notions discussed in the works of the aforementioned. Other significant cognitive and neurological research pertinent to rhythmic and temporal aspects of language will also be considered. Thus, in this paper, I seek to isolate the neurological antecedents of certain phonological structures and explain how neural timing mechanisms motivate and affect their nature within linguistic interpretation (in the English language), with consistent compliance with the cognitive commitment.

Phonological structures:

In respect to the reductionist stance of this paper, it is desirable to reduce language to the simplest forms that play a role in the rhythmic qualities in question, and identify any antecedents. Prosody is the ‘module’3 of language to which phonological structures will be applicable, as this term refers to current use of the elements and structures involved in the rhythmic or dynamic aspect of speech, and the study of these elements and structures as they occur in speech and language generally (La Drière, 1993: 3). Literary prosody is also of interest, as poetic forms of language provide regular rhythmic structures of meter for analysis:

“Literary prosody is not directly concerned with the use which language makes of rhythm for linguistic ends; it is in fact more properly concerned with the use which rhythmic impulse makes of language for its own ends when those are involved with the processes or forms of rhetoric and poetry.” (La Drière, 1993:3)

There are phonological units that have a more pertinent role within the prosody of English4, and there are various interpretations of what constitutes a ‘unit’, bearing in mind that language is systemic in nature, where a finite number of elements form a set of contrasting options within the system, or its sub-system (Clark, Yallop, 1997:57), e.g. the word conflict can be understood in terms of being:

a sequence of seven phonemes; one word; or two syllables, depending on which system we are respecting. (If considering syllable structure of consonants and vowels, the structure is:

CVCCCVCC).

Words, clauses and sentences all constitute phonological structures or units, but their relevance to the timing mechanisms in question is constrained by their occurrence taking place within a 2-3 second time limit, as shall be observed later. In terms of rhythmic structures in verse, it will be seen how they also maintain a duration limitation of a similar time frame.

The phonemic system is less important to rhythmic structures, but in terms of units as functions of rhythm, those that play a role in English stressing are important. The syllable is of particular importance, as stress is a relative property - we hear a syllable as stressed because is stands out against a neighbouring unit which counts as unstressed (Clark, Yallop, 1997:57). Since stress is relative, syllables themselves need not be considered stressed or unstressed.

“In the context of prosodic distinctions, overall syllable duration is more important than segment duration, and relative duration more important than absolute duration” (Clark and Yallop, 1997:281).

There is no indication of the syllable in written English, suggesting that the underlying organisation of speech is independent of that of orthography, and further highlighting the systematicity of language5. The use of the English alphabet could even be considered a metalanguage of the underlying phonology. In terms of the nature of the syllabic system, all languages have syllables and all segment inventories can be split into consonants and vowels, although different languages will undoubtedly have differing constraints on the way segments are combined to form syllables (Gussenhoven, Jacobs, 1998:27-29).

The syllable and feet

Liberman and Prince (1977) realised that stress was not actually a phonological feature governed by some phonetic parameter, but rather a structural position called the foot. This is a suprasegmental phonological constituent above the level of the syllable but below the word level, typically characterised by one strong and one weak syllable, but sometimes taking the shape of triads(groups of three syllables). In verse, line length is described in terms of how many feet there are, and identifiable rhythmic structures of stress occur within forms of poetry and verse. There are various forms of meter which exhibit how phonological units can be arranged in order to constitute a rhythmic structure.

We know that the primary constitutive factors of rhythm in all systems of versification are relations of intensity or of duration. Thus rhythmic structures are based upon counting of syllables, on counting or disposition of ‘stresses’, and on general quantitative or specifically temporal ‘measure’ or balance. According to La Driere (1993), pitch is not the primary factory of rhythm in any known system of verse, although, it may be used with intensity (as duration may) to enforce or even to supply a ‘stress’ and may possibly function similarly with duration.

Contrary to this view, in English it is supposed that pitch is actually the most salient determinant of prominence, ie, when a syllable or word is perceived as stressed or emphasised, it is pitch height or a change of pitch, more so than length or loudness, that is likely to be responsible (Clark and Yallop, 1996:279).

In English there is isochrony, meaning that each foot (regardless of the number of syllables its made of) will take up approximately the same amount of time. This is why English is considered a stress-timed or foot-timed language. This arrangement of stress is likened to morse-code and exhibits eurythmy - avoiding lapses (uninterrupted sequences of unstressed syllables), and clashes (uninterrupted sequences of stressed syllables). These phonological constraints are exclusive to stress-timed languages like English, however free stress systems are observed, e.g. Russian, whereby words can be stressed, in principle, on any syllable with no pure constraints on where the stress may fall (Spencer, 1996d:241).

There are five basic rhythmic groupings or foot types from which English word stress derives: TROCHEE IAMB DACTYL ANAPEST AMPHIBRACH6

+ - - + + - - - - + - + -7

e.g.

water again Pamela intercede romantic

The most frequent foot types found in English are the trochee, dactyl and iamb, giving rise to the trochaic foot, dactylic foot and iambic foot, respectively. Meter in verse uses these types in a regular manner to give rise to its various forms, as shall be seen in the next section. What is of importance is the role that these types have in the literary prosody specified in La Driere’s definitions, not the syllabic manifestations observed in the normal speech of language (although these manifestations are preserved within verse types). I predict that the inherent ‘beauty’ of verse is related to how the three domains of sequential processing converge in a regular and economical way8.

Theories of meter and rhythm

It is useful to gain an understanding of some fundamental principles of what is considered ‘musical’. Within poetic forms of verse are clear schemes and designs, including: The structures of lines of verse; schemes of word order and syntax; patterns of rhyme, assonance and alliteration; strophes and stanzas; overall patterns of variation and repetition; and larger arrangements of these (Hollander, 1983). What should also be remembered is that all poetry was originally oral9, and historically:

“Poetic form as we know it is an abstraction form, or residue of, musical form, from which it came to be divorced when writing replaced memory as a way of preserving poetic utterance in narrative, prayer, spell and the like.” (Hollander, 1983:4)

Poetic forms were used as mnemonics for information, thus the rhythmic structures of verse appear to have a beneficial effect on the ability to encode and memorise language.

Viewed from a totally motor perspective, according to la Drière (1993), it is the rhythmic structure of dance that the verbal rhythms typical of verse have most direct affinity, considering that speech, like the dance, is an organization of bodily movements, utilising the specialized ‘vocal’ organs. He also claims that it is an ordering of the physical movements and pressures which produce sounds that is the basis of rhythm in speech, as opposed to the physical motion or vibration which constitutes the sound.10

Zuckerkandl (1956) views meter as a series of ‘waves’ that carry the listener continuously from one beat to the next. They result not from accentual patterns but simply and naturally from the constant delineation of equal time intervals11.

Meter is defined as: a fixed schematization of the cyclically recurring identity in a rhythmic series12.

There are many metrical systems, but in traditional English verse, the relevant ones are:

1. Pure accentual. This is apparent in nursery rhymes and much lyric verse and derives from the meter of the earliest Germanic poetry.

2. Pure syllabic. Only used in English for the last 80 years or so, this form is prevalent in Japanese and French (centuries of use).

3. Free verse. Many varieties exist, which have mostly developed in the 20th century.

4. Quantitative verse. This cannot occur in English, but was the basis of Greek and Latin prosody.

5. Accentual-syllabic. This is the most dominant form of meter to manifest itself in English verse throughout history, although it has derived from Greek meter system. This form of verse takes shape from pairs (iambs)13 or triads (dactyls) of syllables, whose stress is either grouped or alternated. In English, syllables of words keep the accent they would have in normal speech14. As line length is determined by feet, the following forms of stress pattern can be observed15:

Dimeter 2 syllable pairs (2 feet) Trimeter 3 syllable pairs

Tetrameter 4 syllable pairs Pentameter 5 syllable pairs

of which iambic pentameter is probably the most well known within English verse. It consists of 5 syllable pairs, with the first syllable unstressed. To illustrate, these lines are taken from

Hollander (1983:5), which “most perfectly conforms to the pattern itself.”

Aboút aboút aboút aboút aboút or

A boát, a boát, a boát, a boát, a boát.

Actual poetry takes this form and may make slight variations in terms of using syllable pairings, and obviously differing word sequences, which may change the metrical pattern slightly. The next form (dactylic) is distinguishable from these variations however (the stress is placed on the italicised segments):

Almost the sound of the line of “abouts”

Here the rhythm consists of four beats (as opposed to the five of the iambic), and the unstressed syllables are grouped into triads called dactyls. These traditional forms are not the only observable ones. In the verse of modern music types, more variants of arrangement of feet are observed, but the natural accents of the words are still usually preserved. The conventional forms of meter are used along with spontaneous departure from the norm (within each line), which form the basis of verse in modern western music.

My personal observation is that my memory for verse can be ‘jogged’ simply by the humming of the syllables of one line, or even the tapping of the arrangement of syllables, without having to hear any words phonemes. As a result, the voice can be likened to a musical instrument, whereby the placement of notes corresponds to syllabic placement, and the sentence is similar to the melody. In the perception of language and music, all prosodic features have a role to play and, thus, differences in timbre, notes, note length and pitch can all have an effect on language’s memorablity16. However, the placement of syllables can even be likened to a drum pattern,

without the other variables necessarily playing a role (the tapping analogy). It appears that the placement of syllables in a particular fashion is itself a template which aids commitment to memory and recall:

“An important characteristic of abstract structure (of sequential processing) is that it can generalise to new isomorphic sequences” (Dominey et al., 2002:208).

Dominey et al. (2002) highlight the three dimensions of sequential processing as serial, abstract and temporal. The correlation with these representations is that a sequence of syllables in a sentence can be regarded as a group of serial elements. If these elements were those seen in the example above representing dactylic meter i.e.

Almost the sound of the line of “abouts”, the abstract structure could be represented as:

1-22-1-22-1-22-117, where the ‘1s’ and ‘2s’ correspond to stressed and unstressed elements, respectively. This abstract structure will generalise to new isomorphic structures, thus making the temporal structure of a subsequent line in verse highly predictable:

“Temporal structure is defined in terms of the duration of elements (and the possible pauses that separate them), and intuitively corresponds to the familiar notion of rhythm.”

In light of these apparent parallels between regular systematicity of poetic language, its historical affiliation with memory and its motor skill based origins (memory and motor skill functions being fundamental cognitive processes), one can begin to see that there is more to rhythmic structures of language, and thus language itself, than ‘meets the ear’.

The ‘3 second rule’ and Working Memory

I coined this term, ‘3 second rule’ in regard to similar timing constraint based phenomena expressed within poetic forms, perceptual experience, general discourse, and personally perceived motor based actions (non-linguistic). In actuality, the time frame is between zero and two seconds, without a maximum cut-off point of three seconds.

The perceptual moment and the role of consciousness

Cariani (1999) states that pitch and rhythm are fundamental to the perception of speech, music

and environmental sounds. His analysis highlights parallels between these auditory percepts and temporal discharge patterns of auditory neurons. He also suggests that:

“Segregation by temporal pattern invariance constitutes an extremely general strategy for the formation and separation of perceptual objects” (Cariani,1999: 10).

The cognitive commitment tells us that language and conceptualisation are embodied and experience based, with the view that the human mind and conceptual organization is a function of the way our species-specific bodies interact with the environment we inhabit (Evans and Green, 2004). The consciousness experience is fundamental to understanding the role of temporality in language as it is this which handles the stream of percepts, which must be interpreted by its ‘user’. I personally like to view consciousness as one’s ‘Microsoft Window into the world’.

In light of the assumption that serial arrangement is influenced by the temporal, the constraints on temporality must be observed. The perceptual moment “consists of a temporal interval characterised by the correlated oscillation of neurons, which lasts for a short period of time” (Evans, 2004:15). This is a moment in time of one’s conscious experience, also called a temporal code, where perceptual information is integrated to form a coherent concept. These ‘moments’ are periodic and separated by silent intervals before they re-occur. A ‘temporal global unity’ occurs from the synchronous firing of spatially dislocated neurons correlated by their oscillations co-occurring in the 20-80 hertz range

(Evans, 2004:16). Based on experimental findings by Varela and Ornstein, Evans suggests that perception may be fundamentally temporal in nature, founded by these temporal intervals or perceptual moments. This leads him to conclude that humans have physiological processes which are closely associated with aspects of temporal perception and that the perceptual moment, which underpins perceptual processing, constitutes a possible cognitive antecedent of temporality.

Pöppel (1994, cited in Evans, 2004:22) puts forward the hypothesis that the perceptual moment can be distinguished into two kinds:

Primordial events last for a fraction of a second and operate to integrate or bind spatially distributed information in the brain, between and within different modalities. More importantly, temporal binding (the other form of perceptual moment, which lasts for 2-3 seconds) links primordial events into a coherent unity which, Pöppel argues, forms the basis of our concept of the present. He proposes that it is the temporal binding of 2-3 seconds from which the concept of the present stems18. It is the fundamental ‘phenomenology of time’ that gives rise to the universal neurocognitive temporal antecedents for many forms of processing (if not all), including that of language.

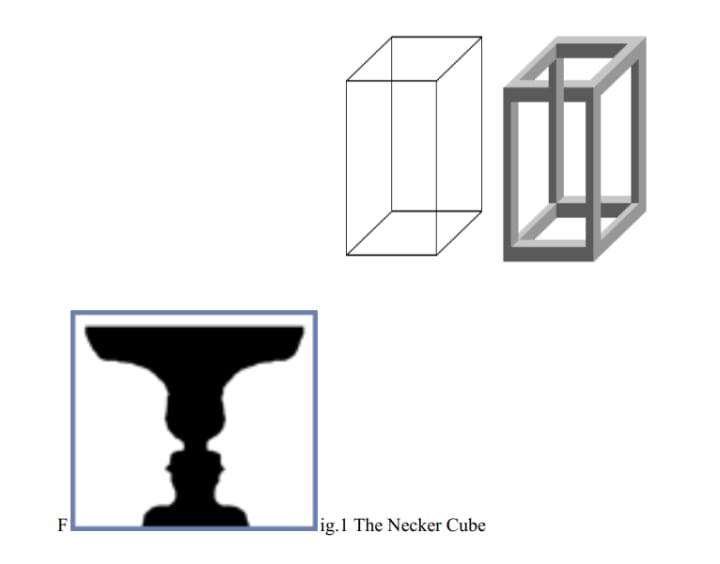

There is much evidence for the perceptual moment having an outer limit up to a 2-3 second range. Ambiguous figures seen in optical illusions such as the Necker cube (fig.1) and Gestalt’s figure vs. ground illusion (fig.2) have a reversal rate of about 2-3 seconds - each perspective is perceived for about 3 seconds before it automatically reverts to the other perspective (if not consciously induced by the viewer). This suggests that perceptual mechanisms re-analyse incoming input, in a holistic way, every 2 to 3 seconds. I personally perceive this form of holistic processing as a human ‘refresh rate’ of consciousness - the oscillations of neurons (followed by silent intervals) being likened to the refreshing of television screens and even the internal clocks of modern CPUs19.

Fig.2 Gestalt’s figure-ground segregation20 (diagrams sourced from online Encyclopaedia Britannica)

Intonation units, Working Memory and the phonological loop

There is evidence that human music, poetry and language is segmented into intervals of up to 2-3 seconds irrespective of a speaker's age. Wallace Chafe (1994) argues that these temporal notions apparent in human conscious flow are also evident in language. Based on analyses of spoken discourse, Chafe divides consciousness into two parts: Focal and Peripheral. He suggests that conscious experience has an active focus of about 2 seconds before it shifts to a new focus. This temporal focus correlates with the temporal antecedent that is the perceptual moment. Chafe proposes that an Intonation Unit21 corresponds to focal consciousness, and based on his analysis of discourse, spoken language appears to be built from these intonation units, which are distinguishable based on prosodic criteria including: breaks in timing; acceleration and deceleration; changes in overall pitch level; terminal pitch contours and changes in voice quality (Chafe, 1994:69). Intonation units can vary in prominence, depending on the information they convey, but the relevance here is the temporal constraint of 2 seconds.

The dynamic value of consciousness appears to be a function of the continual shift from one focal state to another, with previous focal states constituting peripheral consciousness. Chafe (1994: 64) argues that this reflects a fundamental characteristic of focal consciousness, which appears to be only able to focus upon a relatively limited stimulus at any one time. In light of this he also coins the term, the one new idea constraint, which posits that a substantive intonation unit usually conveys some new information, but this information is constrained to one part of the clause (be it the predicate or either referent), and all other elements in the clause will tend to be background or presupposed information (Chafe, 1994: 108-109). There appears to be, within language, this impression of temporal constraint (2-3 seconds), preceded by its cognitive antecedent, the perceptual moment, within which new information is brought to the forefront of the hearer’s consciousness. Within poetry, and other verse of music, it is also observed that the musicality is only preserved when each line falls within this 2-3 second limit22. All of the conventional metered forms discussed in the earlier section exhibit this trend. Most modern music forms also appear to obey the ‘3 second rule’23. If they equivocate, then the hearer would find it harder to follow, merely as a result of the cognitive uniformity of the period of focus.

There is also evidence from experiments on short-term memory which show that stimuli can only be retained for approximately 3 seconds if rehearsal is not permitted.

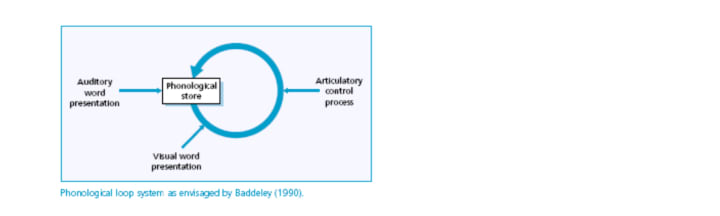

Baddeley (1991 cited in Martincevic & Ravnik, 2000:46) refers to Working Memory (WM) as a system for temporarily holding and manipulating information pertinent to a range of cognitive tasks, including reasoning, learning and comprehension. Baddeley and Hitch (1974) have composed models of this module of memory in which they distinguish 3 systems - the phonological loop, the visuospatial sketchpad and a central executive that coordinates information processing in all modalities. The phonological loop holds information in a phonological form and appears to have evolved from the underlying production and perception systems to facilitate the acquisition of language. It can be broken down into two parts: A phonological store, directly associated with the perception of speech and an articulatory rehearsal system which gives access to the phonological store, and is used in speech production (see fig. 3). The visuospatial sketchpad is concerned with the manipulation of visual and spatial information and is not of real interest, as orthographic representations of language have no inherent rhythmic structure to them - this is only formed when the representations are vocalized in normal or ‘inner’ speech.

The first component of the phonological loop is a memory store that holds a fast-decaying (one to two seconds) speech-based trace, whereas the rehearsal system repeats the trace and registers it in the memory store via non-vocalised speech. Hence when presented with a set of letters (visual and auditory based), they can be remembered by saying it to oneself. However, as the memory trace fades while the rehearsal is going on we can typically only remember as many words as we can say in two seconds. Baddeley conducted experiments involving the memory span task whereby subjects were made to repeat a sequence of items (usually digits) immediately; in the order they were presented. It was found that memory traces within the phonological store fade quickly, if the sequences are not refreshed by rehearsal. Experiments showed that participants could recall as many words as they could read out loud in 2 seconds, suggesting that the capacity of the phonological loop is determined by time duration. (Martincevic & Ravnik, 2000:47-48). This 2-second constraint on (short term) memory of auditory linguistic information appears to mirror the postulation of intonation units and the perceptual moment being possible cognitive correlates. Repetition of the information in the phonological loop, as the experiments showed, enables recall of the sequential information (a series of digits), much as repetition enhances the ability of any other motor skill. It is my prediction that utilizing rhythmic structure within repetition of the units allows the information to be committed to memory, hence the reason for rhythmic structures being used as mnemonics.

WM is a component of Short Term Memory (STM). STM capacity is limited to seven items, regardless of their complexity. Committing items to Long Term Memory (LTM) involves ‘chunking’ of the information present in the STM24 e.g. when remembering telephone numbers (consisting of seven digits), we split them into two units: the first three numbers, then the last four. In terms of sequential processing, this is merely forming an abstract template for a serial set of units. However the temporal dimension of sequential processing also contributes and it is usually observed that there is also a rhythmic structure embedded within the chunks of information.

Neurologically, there have been experiments aimed at locating the regions within the brain which are responsible for the operations of the phonological loop, which shall be reviewed in the next section. Also of importance are the antecedents of temporal mechanisms, the regions responsible for prosodic processing and the processing of music.

Neurological basis of timing mechanisms and language

Phonological loop and other linguistic antecedents

Within the linguistic community, it is well known that there are specialised areas within the brain for the processing of language, namely Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, and the auditory cortex, in particular:

Broca’s: Although its function has not been strictly limited, most studies agree that this area of the frontal lobe, in the dominant hemisphere of an individual, is primarily related to speech production. It is usually associated with maintenance of lists of words, and their constituents, used in producing speech, and their associated meanings. It has also been linked to articulation of speech and to semantic processing. The original area, described in 1861 by Pierre Paul Broca and said to be the ‘seat of articulate language’, has now been further studied and subdivided by functional imaging studies (fMRI and PET) into smaller subsections that each participate differently in language tasks. Semantic processing has been linked to the upper portion of the area, while articulation falls within the centre of Broca's original region of importance. Broca's area is not simply a speech area, but is associated with the process of articulation of language in general. It controls not only spoken, but also written and signed language production.

Wernicke's area is a semantic processing area. It is associated with some memory functions, especially the STM involved in speech recognition and production, as well as some hearing function and object identification25. Wernicke's area is most often associated with language comprehension, or processing of incoming language, whether it is written or spoken. This distinction between speech and language is key to understanding the role of Wernicke's area to language. It does not simply affect spoken language, but (like Broca’s) also written and signed language. Both areas complement each other in language processing, with Wernicke's handling incoming speech and Broca's handling outgoing speech.

In most people (97%), both Broca's area and Wernicke's area are found in only the left hemisphere of the brain, which leads to the commonly held assumption that language is specialised to the left hemisphere of the brain26.

The auditory cortex is comprised of the areas of the brain responsible for recognizing and receiving sound. In spoken language tasks, without correct auditory input, language comprehension cannot occur. As people speak or read words aloud, there is also evidence that they listen to themselves as they are speaking in order to make sure they are speaking correctly. Areas around the auditory cortex, near Wernicke's area, have also been suggested to be involved in short term memory, this area has been isolated as the region responsible for the processing of the phonological loop.

There is also an area called the M1-mouth area, which is responsible for controlling the physical movements of the mouth and articulators used in producing speech. It is part of the motor cortex and controls the muscles of the face and mouth. It is not connected with the cognitive aspects of speech production, though it is located near Broca's area and is activated in speech tasks along with Broca's area27 (www.memory key.com).

The above areas are traditionally assumed to be the major contingents in the module of language processing. They have been identified through a series of techniques, ranging from the earlier (1960s) employment of the Wada Test (which uses a fast acting anaesthetic called sodium amytal (amobarbital) to put one hemisphere of the brain asleep), to recent research techniques involving positron emission tomography (PET) studies and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which have shown that many of the expected areas of the brain have increased blood flow during language tasks. These studies have also shown that there are areas on both hemispheres that are activated. Therefore, it appears that the hemisphere that is not dominant for language (usually the right side) does have some involvement in language. It has also been observed that people have problems communicating the emotions involved with language when they have damage to the right side of the brain in the area where on the left side it is used for language. This disorder is called aprosodia28.

These associated regions appear to be related to STM, WM and the phonological loop. In the break down of neurological antecedents of the phonological loop using fMRI, it was found by Baddeley that:

“Separate areas are implicated in storage and rehearsal, namely a left inferior parietal area in the former and left prefrontal areas in the latter” (1986: 439).

Further studies by Paules, Frith and Frackowiak (1993, cited in Martincevic & Ravnik, 2000:47) support this idea. They found, using PET and fMRI, that the left temporoparietal junction at the supramarginal gyrus has a unique role, operating as a short term phonological buffer, with Broca’s area apparently specialised for rehearsal purposes as opposed to short term storage29. The short term storage has been thought to correlate with parietal lobe activation, based on studies by Jonides et al., (1998 and Awh et al., 1996, cited in Ivry et al. 2001: 201).

Motor based timing

Sequential processing of any motor skill requires a specific temporal pattern of activity across the relevant muscles, emphasizing that the temporal information underlying motoric (and sensory30) processes requires correct perception and production of intervals (The cognitive commitment tells us that conceptual structure is embodied, and perception based. Perception and production of temporal information stem from the same architecture). There are two forms of timing mechanisms that are responsible for motor output. Human studies have suggested that there is a qualitative change in temporal processing for intervals longer than 1.5 - 2 seconds31.

Hazeltine et al. (1997) hypothesise that the cerebellum is critical for timing for these shorter intervals, and that other structures such as the cortex and basal ganglia perform for longer intervals. Meck (1996 cited in Hazeltine et al., 1997:5 ) proposes that the basal ganglia system forms a pacemaker-accumulator mechanism and the frontal cortex is associated with temporal memory and attention. Further research of (damage to) these structures has shown that damage to the cerebellum results in a ‘noisy’ timing system and basal ganglia lesions result in a change in the clock speed.

The Automatic Timing System may indeed have an effect on the overt rhythmic aspects of language within the 2-3 second range. This system most “likely recruits timing circuits within the motor system that can act without attentional modulation.” (Lewis & Miall, 2002:518).

Driven by the cerebellum (which has an important role in automated actions32), this form of temporal interval processing is appropriate for motor tasks, which, once selected and initiated, are performed automatically. Speaking in verse with a predictable abstract structure is, essentially, an automatic motor task. However, this timing mechanism is unlikely to serve in all circumstances, and a Cognitively Controlled Timing System may be required when intervals are longer than a second or so and are not part of a predictable sequence. This system is used for analysing intervals longer than a second that are not defined by movement and are considered discrete events, as opposed to parts of a sequence (Lewis & Miall, 2002:518).

Numerous theorists have previously suggested, based on neurophysiological, behavioural, and computational evidence, that the cerebellum has a central role in controlling the temporal aspects of movement. It is considered to be located in the ‘centre of the motor pathways’ due to afferent and efferent pathways linking it to the cerebral cortex, brainstem and spinal cord. According to Hore et al., (1991, cited in Ivry et al. 2001: 196), patients with cerebellar damage are able perform complex computations in goal or object manipulation, but their deficits become apparent when the required muscular events require precise timing. This region is adjudged to make major contributions to (timing), learning and skill acquisition. A hallmark of skilled behaviour is that it is performed in a consistent way. Damage to the cerebellum often results not in loss of ability to perform a learned action, but loss of integration of the movements into a coordinated whole, so that movement appears fractionated into a set of poorly connected subunits. In reference to language, patients with cerebellar damage frequently exhibit speech disorders. Known as cerebellar dysarthia, speech can show irregularities in stress and rate, and phonation may be erratic. Some patients tend to speak in a loud voice, enunciating every sound33 (Ivry et al.,2001: 194).

“[T]he cerebellar role in speech production is another manifestation of its general contribution to coordination”(Ivry et al.,2001: 192)

Being the quintessential skill exhibited by humans, there is more to language than mere motor skill. Novel polysynaptic tracing techniques have been used to identify outputs from the cerebellum, not only to the motor regions, but also to innervate prefrontal regions that are assumed to have great influence on higher cognitive functions (Ivry et al., 2001:196), which suggests a wider network is involved in language, comprised of more than just the known specialised areas.

An interesting condition that excludes actual damage can be seen in people with stutter based impediments, who are considered to be victims of a ‘speech-motor control problem’:

“[W]hen a person stutters on a word, there is a temporal disruption of the simultaneous and successive programming of muscular movements required to produce one of the word’s integrated sounds…”(Van Riper, 1982: 415).

Research conducted by Webster (1988, cited in Forster, 2002), based on sequential finger tapping and other bimanual tasks showed that the sequential response mechanisms in people that stutter are particularly susceptible to interference from ongoing activity in the contra lateral hemisphere. He based these conclusions on the presence of mirror reversals34 exhibited by ‘stutterers’ who performed these tasks. Mirror reversals are strongly suggestive of interhemispheric overflow or interference35. Subsequently, Forster and Webster (1991, cited in Forster, 2002) concluded that people who stutter do not have damage to sequential motor control systems, but rather are unusually more susceptible to interference, which leads to an increased tendency to experience momentary breakdowns in the fluent sequencing of complex sequential motor processes.

Neurologically, Webster found that the supplementary motor area (SMA) is involved in the temporal programming of complex motor sequences, and those with SMA damage exhibit language deficits similar to those with a stutter. As experimental research was based mainly on patients ability to handle bimanual tasks, the findings showed that the SMA may be partly responsible in coordinating the bilaterality of overall programming of speech tasks36(Webster, 1988, cited in Forster, 2002)

Dysprody effects

The fact that the linguistic elements in question are part of the prosodic system begs for analysis of dysprosody. Identifying the role of timing mechanisms and constraints requires a view of prosodic function as a whole and a broader picture of these mechanisms at work. Using neurological evidence from dysprosodic patients, regions responsible for analysing prosodic features in language can be highlighted. Clinically, prosody has often been studied, in principle, as a conveyor of emotional expression in speech, responsible for distinguishing a speaker’s stance, attitude and even personal identity (attitudinal and affective uses). Linguistically, prosodic features can make a sentence a statement or question, and render it restrictive or non-restrictive (Sidtis and Van Lancker Sidtis, 2003:94). The higher order semantic features of prosody, which are traditionally analysed, are of less concern in this case, and the temporal blueprints of which speech units are mapped onto are of most interest.

Findings have spawned 2 schools of thought about the neural nature of prosody: Some neuroanatomic evidence from brain-damaged patients suggests that perception and production are two independent modes of processing, while others contradict this view. What is widely accepted is that while the left hemisphere is responsible for lexical, syntactic and phonological representation and analysis of language, the cerebral representation of prosody is still undetermined. The idea that affective prosody is mediated by the right hemisphere is unsubstantiated and oversimplified, while negated by the fact that dysprosodic patients are rarely found to have right hemisphere damage. Studies have identified that, due to the complex nature of prosody, dysfunction can stem from damage to the central nervous system from brain stem to cerebral cortex resulting in abnormalities in perception and expression of the prosodic features of pitch, timing, coordination, and intensity. Damage to the basal ganglia can cause dysprosodic deficits across a range of tasks, including symptoms of tremor, athetosis, ballism and chorea (movement disorders which can alter prosody). This area is judged to be involved with the Cognitively Controlled Timing Mechanism and the pace-maker accumulator system.

Cerebral damage has been shown to produce ataxic speech (this condition affects articulatory coordination and timing). Although there is a known bilateral neuroanatomical basis for the processing of emotion, studies by Borod et al., (1996, cited in Sidtis and Van Lancker Sidtis, 2003:99) have shown that right hemisphere damaged patients produce less emotional content than their left hemisphere damaged counterparts. The important factor is that dysprosodic phenomena can result from damage to a large number of brain regions, not necessarily homologous to language areas. As a result it is assumed that multiple etiologies may underlie prosodic disturbances. This contradictory view is bolstered by studies which show no difference between those with either left or right hemisphere damage, when subjected to linguistic or emotional stimuli (Sidtis and Van Lancker Sidtis, 2003:98).

The functional lateralisation hypothesis (Baum and Pell, 1999: 590) stated that attitudinal/emotional and personal voice quality recognition are lateralised to the right hemisphere, while motoric/acoustic features that are functionally utilised (i.e. phonemes, syllable, words, clauses), are lateralised to the left. There is evidence suggesting that the right auditory cortex is specialised for complex pitch perception, as well as studies showing that durational characteristics emerge from the left. Temporal judgments are commonly considered to be left specialised, with disturbances in rhythm perception seen in patients with left, but not right, hemisphere lesions. As rhythm in language is an amalgamation of timing and pitch, it can be inferred that this quality is ‘brain-wide’ and not just specialised in the left hemisphere37. Left hemisphere damaged patients show errors in prosodic comprehension as a result of misjudging timing cues as opposed to pitch, but right hemisphere patients have shown disturbances in their use of temporal cues when processing affective prosody (Sidtis and Van Lancker Sidtis, 2003:97).

One could assume from this that language competency involves a cross-hemispheric combination of prosodic information. In my opinion, it is this complexity of prosody that potentially creates parallels between voices and instruments. The pace-maker of the basal ganglia, and the automated timing mechanism of the cerebellum have been shown to play a role in prosodic processing, as well as other cognitive processes. While phonological representations are important for human communication, what is also observed is that:

“[T]he computational machinery for analysing speech sounds appears to use similar processes as involved in other types of auditory perception” (Ivry et al.,2001: 196).

Also, according to Cariani’s(1999) computational models of auditory function analysis:

“Studies of conditioning, music perception and rhythm production suggest that temporal relationships are explicitly encoded in memory, and that these relationships create sets of temporal expectancies” (Cariani, 1999:2).

What has been observed is that the neurological antecedents of rhythm and timing can be attributed to a wide range of areas of the brain. The WM and the phonological loop system, which correlate to temporal constraints of focal consciousness and intonation units, were found to have antecedents in brain regions involved in linguistic processing, namely the parietal and frontal lobes - in proximity to both Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas. These areas are found to be activated mostly in the left hemisphere when tested with linguistic tasks. The timing mechanisms which are pivotal in sequencing cognition, within the temporal conscious constraint, are distributed across various structures including the basal ganglia, the cerebellum and the SMA. The location of rhythm as a prosodic feature has neural roots in both hemispheres (due to the pitch processing taking place in the right and durational processing attributed to the left. Actual rhythm being an amalgamation of the two distinct prosodic properties). In light of these neural correlates, and considering that prosody is deemed to constitute the ‘musical’ elements of language, closer scrutiny of processing of sounds in a holistic manner is necessary.

Cortical language network theory

Research by Koelsh et al. (2000) showed that much of the cortical network identified for language specialisation (and assumed to be exclusive to language), was activated when they investigated the neural correlates of music. Using fMRI analysis, they discovered that the areas including Broca’s and Wernicke’s, and their contra hemispheric homologous regions, were active during the processing of melodies, in both musicians and non-musicians. The melody is considered a one-part stimulus, as is the voice, as opposed to the multi-part stimuli of chords, however a single melody has an implicit harmonic structure albeit with much less harmonic information than that of a harmonised melody. The studies were based upon presenting non-musicians with sequences of chords, played on the piano, that were composed in such a way that musical context was built up towards the end of each sequence, much like semantic context is built up in a sentence. The sequences were composed according to the principles of the Western ‘major-minor’ tonal system, and participants were asked to detect sequences with dissonant clusters (salient violations to the musical expectancies of the listener) or deviant instruments, but only respond (by means of button pressing) to the deviant instruments. Clusters are similar to musical modulations (movement of the tonal key, to another key), but can only be detected by application of implicit knowledge of music theory - harmonic distance and relatedness in particular (i.e. the major-minor tonal system). From the results, the term musical syntax was coined to denote these principles of harmonic relatedness and distance. It was found that listeners expect chords to be arranged harmonically close to each other, within a given sequence. The brain regions found to be active during these perception tasks showed that the cortical language network is less domain-specific than previously believed (Koelsh et al., 2000:960). These findings support the hypothesis that the human brain has an inherent ability for highly differentiated processing of music, considering that the participants were all non-musicians.

In terms of hemispheric function, the findings suggest that there is no strict lateralisation of language processing to the left and music to the right. While the common assumptions of most prosodic processing occurring in the right hemisphere were supported, the experiment suggested a strong interaction of both hemispheres for both language and music processing and that sequential auditory information is processed by brain structures, less domain specific than previously believed. As a result of their findings, Koelsh et al. also propose that musical elements of speech may play a crucial role for the acquisition of language and that human musical experiences may be able to implicitly train the language network. There is also the suggestion that these findings may give rise to new therapeutic and didactic implications (Koelsh et al., 2000: 964).

The latest research on the basis of music and language processing, conducted by Altenmuller (2003), has shown similar results to that of Koelsch et al. His studies conclude that humans perceive music as more than just sound, and that there are 6 billion unique ‘music centres’ in the world (each person perceives music in an individual way).

From a cognitive perspective, it appears that language processing is not a distinct module, but that auditory computation involves a distributed ‘linguistic instrument’ across the network of the brain, which uses higher cognitive functions simultaneously with those specialised for motor control.

Chafe (1994) posits, based on comparative analysis of 18th Austrian piano sonata, and American Indian Seneca music, that:

“[A] wide range of music is fundamentally influenced by the same patterns that govern language” (1994: 191).

The nature of the linguistic instrument has been discussed in terms of its bilaterality, as opposed to the previous assumptions of language specialisation occurring in the left hemisphere. As music appears to be so closely tied in with language perception, the fundamentals of non-linguistic sound experience can also provide a template for analysing certain linguistic qualities.

It appears that the forward linear progression of time has implications on the sequential structure of certain behaviour. Time is divided into moments, within which intervals between units of information are further divided into structures, which, in essence constitutes the rhythm of the information within the sequence. Language places the highest demand on the ability to store and manipulate sequential information, being the most highly developed form of cognitive sequence processing. While language is highly specialised in itself, there is neurophysiological and functional overlap between linguistic and non-linguistic processing.

Dominey et al. (2003) produced a model of sequential processing based on experimental findings in human and non-human primates. They observed that:

“[L]anguage has the same processing status as that of any cognitive sequence system in which configurations of function elements govern the application of systematic transformations, as in domains of music, mathematics, logical theorem proving and artificial symbol manipulation tasks” (2003: 217).

They also observed in non-human primates38, that they were able to coordinate sensorimotor tasks, and that brain regions responsible included activation in the prefrontal cortex and between cortex and basal ganglia (the former associated with WM and the latter with timing of movement mechanisms in humans).

In the study, they also observed that Broca’s aphasia, which is responsible for the rehearsal role of the phonological loop, led to an impaired ability to extract abstract structure from given sequences. As the abstract allows one to generalise over new isomorphic structures, and can be correlated with syntax, learning a temporal structure will be impaired if one cannot generalise using the abstract domain. The symptoms of Broca’s aphasia range from an impairment of the output of speech to total loss of speech altogether and it is also known as Motor aphasia. The correlation here appears to be between the motor nature of language and an inability to generalise over the complex patterns of rhythm so prevalent in language. The phonological loop is thus constrained by the 3 second rule and underlying timing mechanisms (which govern rhythm perception and production) for appropriate rehearsal of language.

Discussion: The nature of linguistic timing

Conclusions

There appears to be a manifestation of underlying timing mechanisms in the production of human poetics and music. The nature of language is similar to that of music, but the fact that musical forms are so appreciated may well be associated with the same underlying apparatus that make highly skilled persons seem so consummate. Watching skilled sports persons, technicians or musicians at work (or play) is awe-inspiring because they have mastered the timing functions of their motor skills, in their field, through repetition.

Those with timing related brain dysfunctions exhibit difficulty or inadequacy in motor or language based tasks, or both, and so the timing mechanisms of the cerebellum and SMA in particular appear to motivate proficiency in this component of cognition. The mnemonics of language can be harnessed through repetition, and the underlying categorisation responsible for forming predictable rhythmic structures also appears to have effect. Timing mechanisms coordinate many cognitive tasks and there seems to be benefits of ‘getting in time’ with oneself, especially during the critical period of acquisition

i.e. there are always references to learning or acquiring a skill at a young age in order to become ‘dexterous’. It is also believed that melodic aspects of adult speech to infants represent the earliest associations between sound patterns, meaning and syntax for the infant, due to musical elements nurturing linguistic abilities earlier than phonetic elements (Trehub et. al., 2000, cited in Koesch et al., 2000: 963).

However, being able to improve abilities within the language domain by training in the musical domain has also been seen in adults, according to research by Chan et al., (1998: 128). One must note that musical training is a marriage of motor skill to acoustic perception, much like language. There are benefits for language via musical tuition, as language processing is more complex than the lateralised theory, however, the underlying motor timing mechanisms are more fundamental to this form of nurture, as this has implications for everything that stems from the cognitive functions of sequencing and planning.

Haffey (1998) conducted research into the effects of learning a music instrument from a young age. Considering that verbal memory is primarily mediated by the left hemisphere and visual memory is mediated by the right hemisphere, adults with music training should have better verbal memory (but not visual memory) than non-musicians. Researchers found this correlation to be true in the study. She also found that there is a notable increase in the size of a musician brain, apparently due to cortical reorganization i.e., better connections between brain cells or more brain cells, and concluded that some cognitive functions also mediated by the left side of the brain may be more developed in musicians.

In light of Koesch et al.’s suggestion that the musical elements of speech may give rise to new therapeutic and didactic implications, maximising one’s ability to use the cortical (not just) language network can be seen at The Davis Centre39. The Interactive Metronome (IM):

“[P]rovides educational technology aimed at facilitating a number of underlying neural timing related planning and sequencing central nervous system processing capabilities that are foundational to our ability to attend and learn” (www.IM.com).

The therapy is useful for any motor skill, concentration, thinking, and social interaction, and is based on using simple limb movements as ‘systematic outward rhythmicity catalysts’ to an underlying mental control improvement process. The therapy has proven to assist with deficiencies in motor skill, attention and language deficits and appears to be testament to the relationship between rhythm, motor and language.

While there are factors of tone and rhyme and other complexities of the linguistic instrument40, the underlying temporal domain of timing undoubtedly has a large effect, much as it does with motor skill (from which language emerged41), where it may be the dominant factor.

The limitations of this study arise from the glut of information available in regard to the topic at hand, and the limited word capacity of this paper. With more time and space, a more coherent argument can be made from more (albeit less interesting!) sources. In terms of the methodologies for identifying neural correlates, the current fMRI and PET technologies, while competent, can only show increased blood flow into brain regions, which is considered representative of responsibility. In reality, this behaviour may not necessarily, or may only partially correlate to the tasks under investigation due to the holistic distribution of processing across the network of the brain.

References/Footnotes

1 All behaviour in the universe (not just language) is emergent, according to Max Velmans (2000).

2 From an evolutionary perspective, spoken language was preceded by sign language, of which gesticulation is a relic.

3 Indeed,

4 ...being a stress based language, the units of relevance may be different in a tonal language such as Mandarin.

5 Although awareness of a writing system facilitates a certain awareness of segments and

structure, the absence of written expression does not rob spoken language of its systematic nature 6 The names have derived from Greek traditions of analysing poetic meter.

7 ‘+’ represents a stressed syllable, ‘-‘ represents unstressed syllables.

8 NB The three dimensions only at least partially span the space of possible behavioural sequence structure and realistically, more research is needed.

9 which reinforces the earlier assumptions of the spoken system being independent of orthographic representation.

10 another reference to the motor nature of language.

11 Pitch contours are ‘waves’ of peaks and troughs that constitute stress. 12 Online dictionary definition (www.dictionary.com)

13 e.g. delay.

14 Accent ‘loosely’ means stress. 15 To name a few.

16 The actual correlation between language and music processing shall be discussed in a later section.

17 This structure is also seen in the ‘contagious’ jingles of cheerleaders.

18 Hence Evans’ conclusion that the perceptual moment is a valid candidate for a cognitive

antecedent of temporality: The perceptual moment corresponds to human conceptualisation of ‘now’, and conceptualisations of ‘before’ and ‘after’ stem from these moments.

19 Velmans, Edelman and Tononi (2000) suggest that the conscious experience is a ‘set of stills’ not a continuous flow, which comprise the illusion that is the ‘remembered present’ of the

conscious experience.

20 The figure Vs. ground segregation observed is a manifestation of focal and peripheral information in consciousness. Only one (figure or ground) can be focal at any one perceptual moment. In language this is seen in the selection of privileged participants in a given construal. 21 His coinage

22 The various tempos of modern western music have verse line lengths which fall within this range.

23 While there are obviously some exceptions, the majority exhibit similar formulaic structures which conform to the rule.

24 An economical way of categorising more items into groups. 25 The apparent antecedent of some phonological loop functions.

26 Many left handed people have the right hemisphere specialised for language.

27 The proximity of motor skill areas and language areas further reinforce the notion of language being emergent from motor skill.

28 NB the emotional effect music can have on the listener – more on this later.

29 The supplementary motor area and the cerebellum also have roles in control of the articulatory rehearsal system.

30 According to Hazeltine et al. evidence for a common timing mechanism can be observed in the tendency for bodily movements to become automatically entrained with external stimuli, e.g. moving to the beat when we enter a nightclub.

31 (!) Perceptual moments come to mind

32 The clause is automatically, unconsciously planned, as one only knows what they are saying, once they have said it.

33 In other words, pitch and stress variation is minimised.

34 An example of which is writing reverse symbols or words with the ‘wrong’ hand when asked to simultaneously write with both.

35 This supports the ungated callosal function hypothesis, which supposes that each hemisphere is particularly susceptible to interference from homologous regions in the contra lateral hemisphere, via the corpus callosum.

36 The production of fluent speech involves precise temporal integration of the activity of the 2 sides of the speech apparatus, governed by the 2 hemispheres of the brain. As a result, the lateralisation of the brain for language purposes can be questioned when temporal notions are

considered.

37 Note also the other structures identified for temporal based mechanisms i.e. Cerebellum, motor area and SMA.

38 Of interest because they are primates like humans, just separated by language, which has not evolved from the same antecedents.

39 This is a therapeutic centre, specialising in development, learning, and auditory processing.

40 Pitch and tone are lateralized to the right, and constitute the emotional elements. This may be ascribed to nouns and verbs (high semantic value), whereas function words are non-emotional

elements of a linguistic series (with lower semantic value) – the music of language may be lateralized to this function

41 In terms of universal emergence, the frequency of neural oscillations can be represented as ‘peaks and troughs’. The rhythm of timing mechanisms and the rhythm of phonological

structures is also representable in this way.

1

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.