Mirrored Emotions: Decoding the Anxieties of Our Time

Why We Feel So Bad in an Age That's Supposed to Be Better

Emotions are no longer private islands but externalizations of our collective unconscious, quietly tracing the contours of our era’s psyche.

A series of recent studies mapping the trajectories of public sentiment reveals the deeper textures of contemporary society—anger harnessed for clicks and shares, anxiety bred by uncertainty, crises latent within income gaps, and new dilemmas emerging amidst progress toward gender equality.

These emotional phenomena reflect not just individual interactions with the times, but also hidden projections of our social structures.

The coining of “rage bait” as the 2025 Oxford Word of the Year perfectly captures the emotional landscape of the digital age. This term, referring to “content deliberately designed to provoke public anger and generate online engagement,” saw its usage triple over the past year, confirming that outrage has become a core “engagement driver” in the digital ecosystem.

Its key difference from mere “clickbait” lies in its deliberate manufacturing of group conflict and polarization, further giving rise to systemic manipulation practices like “rage farming”—the continuous seeding of inflammatory content to cultivate and harness audience emotion over time.

As Casper Grathwohl, President of Oxford Languages, notes, this forms a vicious cycle with last year’s Word of the Year, “brain rot”: anger drives interaction, algorithms amplify emotion, ultimately depleting individual cognitive capacity. Language, as a mirror of culture, has been exposing how digital platforms reshape human thought and behavior.

Economic uncertainty, meanwhile, is mass-producing anxiety. A study spanning nearly 30 years across 110 countries shows that for every standard deviation increase in the World Uncertainty Index, the prevalence rates of anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder rise by approximately 10.77 and 11.09 cases per 100,000 people, respectively, with the latter effect exhibiting both persistence and a lag.

Unlike traditional economic indicators, this index better captures broad risks from political turmoil and natural disasters. Here, women, individuals aged 15–39, and those over 55 show greater sensitivity to economic fluctuations.

Those in later middle age face particularly high risks of major depression, where economic pressure often compounds the challenges of aging, becoming the final straw for mental resilience. What truly wounds is not just harsh economic reality, but the persistent dread of an “unknown tomorrow.”

Widening income inequality is quietly elevating suicide risks, echoing Émile Durkheim’s assertion in Suicide that it is a phenomenon rooted in social structure. Research based on data from 158 countries between 2000 and 2019 indicates that for every unit increase in income inequality, the suicide rate rises by an average of 0.162 units.

This impact is more pronounced in regions with lower governance quality. Gender differences are also stark: men, often bearing greater economic responsibility and societal pressure to embody “stoicism,” are more severely impacted by income disparity.

Notably, while inequality correlates positively with suicide rates in low- and middle-income countries, the relationship reverses in high-income nations—a divergence largely attributed to differences in the robustness of social safety nets and support systems. In conflict-affected countries, the combination of traumatic experience and inequitable resource distribution further amplifies the lethal risk of income gaps.

Perhaps most thought-provoking are the new dilemmas surfacing within gender equality progress. A 20-year survey of 1.26 million adolescents across 43 countries found that in nations with higher gender equality, the mental health gender gap among teenagers is actually larger, with girls reporting more psychological symptoms and steeper increases.

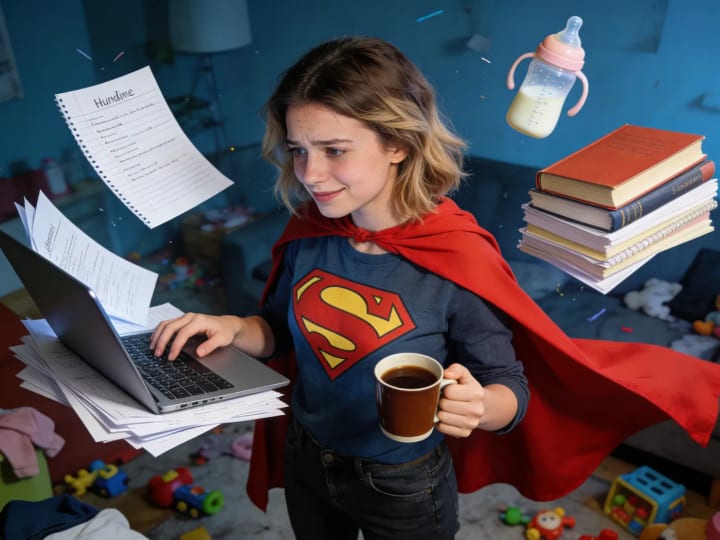

This is not a critique of equality’s value, but a revelation of its “surface-level” flaws. Girls are now burdened with an “effortless excellence” expectation — to excel academically while also managing traditional roles like emotional labor and appearance management, creating a “superwoman double burden.”

Coupled with intensified social competition, pervasive meritocracy, and a heightened, more acute awareness of remaining injustices fostered by greater equality, this collectively worsens girls’ psychological state. The research warns us that merely adding responsibilities and expectations to women without building supportive systems risks turning equality into a new source of inequity.

From the algorithmic taming of anger to the mass production of anxiety, from the psychological erosion of income divides to the hidden pitfalls of gender progress, the emotional landscape of our time is, in essence, a concentrated projection of our era’s core tensions.

These emotions are not monsters to be slain, but signals urging us to examine how our society functions. Only by confronting the structural contradictions behind these feelings — and by committing to ongoing efforts in digital ecosystem governance, social safety net development, equitable income distribution, and the construction of genuine gender support systems — can we allow individual emotions to find their place and collectively shape a more temperate and inclusive spirit for our age.

About the Creator

Cher Che

New media writer with 10 years in advertising, exploring how we see and make sense of the world. What we look at matters, but how we look matters more.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.