Beauty Can Be Terrifying

Do we fear life?

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke is, aside from being my favourite fiction book I have ever read, a perfect example of beauty and the sublime. While this is not a review of the book, it serves as a perfect illustration of what we are going to discuss: the limitless and boundless beauty—and horror—of the sublime.

Piranesi is trapped (though he does not know it) in a universe that consists of nothing but a house. The House. A vast structure with kilometres of walls, rooms, floods, wildlife, and classical art. Piranesi is alone in this place most of the time, and he repeats one special motto:

“The Beauty of the House is immeasurable; its Kindness infinite.”

This brings us to Immanuel Kant:

“Whereas the beautiful is limited, the sublime is limitless, so that the mind in the presence of the sublime, attempting to imagine what it cannot, has pain in the failure but pleasure in contemplating the immensity of the attempt.”

— Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason

The idea of the sublime in art, first formally explored by Edmund Burke in 1757, describes experiences that evoke powerful, often terrifying emotions. Burke distinguished the sublime from beauty, yet acknowledged the deep sense of immersion humans feel when confronted with vastness or danger.

Earlier thinkers also linked awe to terror. John Dennis, after a harrowing journey through the Alps in 1693, described nature as both breathtaking and frightening. Shaftesbury, who made the same journey, saw beauty and sublimity not as opposites but as different degrees of awe, extending his ideas to the immensity of the cosmos and humanity’s small but meaningful place within it.

Ultimately, the sublime captures the mixture of fear, wonder, and inner vision, as later echoed by artists like Caspar David Friedrich.

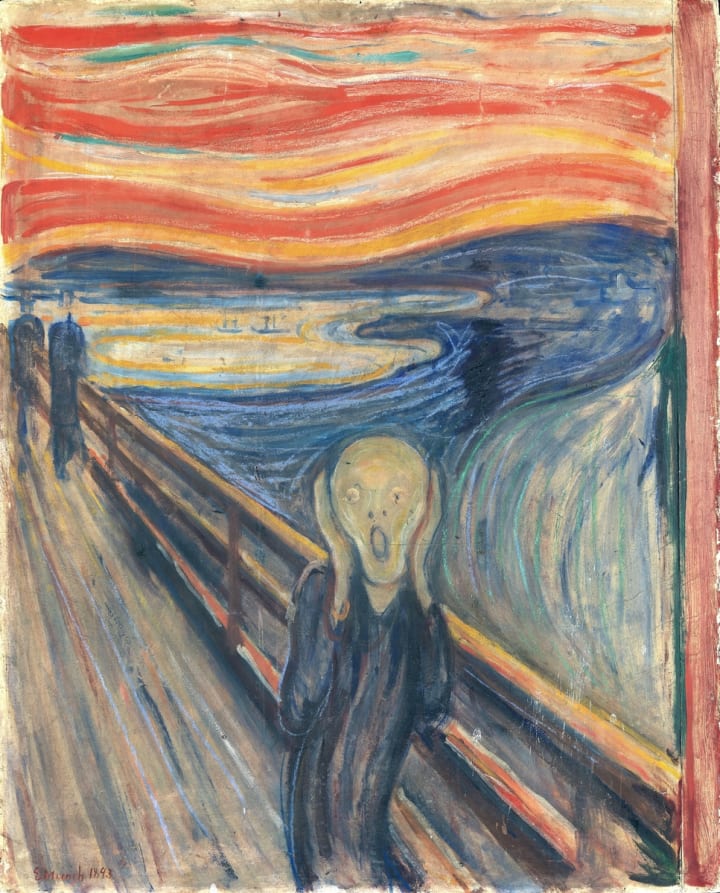

The one painting that encapsulates the horror and beauty of the sublime better than any other is Edvard Munch’s famous The Scream.

An interesting question, once the work of art is created, is why we find such horrific scenes beautiful. Surely fear, like pleasure, is an arousing state: you get a spike of adrenaline, your heart beats faster, and the experience becomes memorable and exciting.

But what we find beautiful in the scariness of the sublime is safety. Piranesi, after all, felt that the House was his goddess, kind and beautiful.

In psychological terms, cognitive appraisal can either perpetuate the instinctive fear reaction or diminish it if the perceived danger is minimal or deemed safe.

We are left, when standing before a Turner or a storm, with the aftermath of fear, a rush of euphoria: we are alive!

In fact, one of the most euphoric and mentally disorienting genres of art is cosmic horror, which, like the sublime, has much to do with vastness, greatness, and at times, beauty.

“Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe, or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.”― Arthur C. Clarke

H.P. Lovecraft’s The Nameless City embodies cosmic horror through its portrayal of an ancient, incomprehensible city, alien architecture, and hidden creatures that emphasise humanity’s fragility and insignificance. The protagonist’s descent into madness illustrates the dangers of pursuing forbidden knowledge and confronting realities beyond human understanding (again, we find parallelisms with Piranesi's experience in the house).

What is scary is that the story highlights a universe indifferent to human existence.

Lovecraft’s legacy continues in works like Junji Ito’s Hellstar Remina, where a planet-sized monster devours worlds and targets Earth. The story explores existential fear, helplessness, and the terror of facing an unfathomable cosmic entity—ultimately ending with humanity being consumed.

Both works show that what truly terrifies us isn’t just monsters but the overwhelming concepts behind them: the vast unknown, our insignificance, and the confrontation with a universe that is both beautiful and horrifying at the same time.

Beauty can be ‘horrific’, awe-ful. Much like everything grandiose. Religion and mythology themselves have in many ways understood this connection. We wrote stories of rage and storms, apocalypses, secrets and punishments passed on the top of mountains, and humans succumbing to or winning against the supreme strength of the oceans.

If I had to place a wild guess, I’d say that most of our feelings and needs when confronted with the sublime, the vast, the bigger than us and out of our control, have to do with the primordial fear of death.

At least it is most surely the case with me.

Understanding that against the infinite universe we are finite reminds us of our inevitable demise, and I’d say that the same goes for the unknown. I can also attest that, for at least one human on this planet, feeling ‘awe and terror’ when confronted with these ideas, even subconsciously, while observing nature or art, being ‘awestruck’ evokes physical reactions not dissimilar to those of anxiety. And what is panic if not the fear of the unescapable?

We fear not death itself, but the turmoil and dread that surround it. Much of human suffering comes from feeling trapped within our own existence, aware of our insignificance yet burdened by the knowledge of it. Still, even within this fear, beauty can emerge; a beauty that may justify the struggle of being alive.

Our smallness in the universe is both terrifying and meaningful. We suffer, but only because we know; and knowing is part of what makes life profound. This idea echoes through Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, where the protagonist, Piranesi, ultimately realises that seeking unreachable, “Great and Secret Knowledge” is futile. Instead, he discovers that the House — like life and beauty — is valuable simply because it exists. It is enough in itself.

About the Creator

Avocado Nunzella BSc (Psych) -- M.A.P

Asterion, Jess, Avo, and all the other ghosts.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.