Are emotions still useful in the 21st century

Is it not better to live a life of productivity rather than emotion?

Humans seem too emotional. Why can’t we just get rid of our emotions and use logic in our daily lives instead?

This was a question a friend of mine asked recently over dinner, an inquiry about our human nature.

Imagine standing in front of a massive crowd, thousands of people spread throughout the hall, all waiting for you to speak. You had something prepared, you know you did, but you can’t remember it right now. Or consider the immense frustration you feel when there’s a task you want to do, but seem just unable to start.

These issues, and so many others in our daily lives, are all the result of emotions. So let’s try getting rid of them.

What are emotions?

Before we wipe emotions out entirely, we must understand what they are.

Emotions are this strange, ever-present condition of the human experience. It’s near-impossible to have any experience without some emotion attached to it. They can bring happiness and joy, love and wonder and awe. Or they bring us anger, sadness, and depression, along with feelings of loneliness, inadequacy, and grief.

The origin of emotions

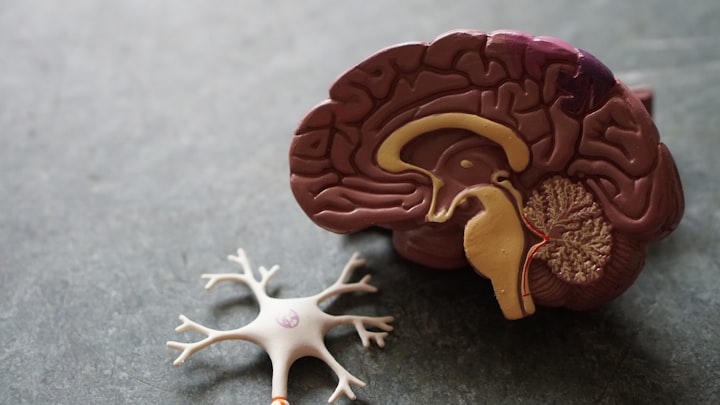

In your brain is the amygdala — a small, almond-shaped cluster of nuclei located deep within the temporal lobes. Despite its small size, it is a crucial part of your brain in how you experience emotions. It triggers an emotional response when it perceives something significant, either real or imagined.

The amygdala evolved as a survival mechanism. In our early ancestors, it was crucial for detecting threats, like a predator lurking in the bushes or poisonous foods. Upon sensing danger, the amygdala sends out signals to prepare the body for a fight-or-flight response, ensuring survival.

But where do emotions actually come from?

Two major theories aim to answer this question.

The James-Lange feelings theory of emotions claims that emotions stem from the physical feelings and sensations before the associated conscious, what we call “emotional” experiences.

Essentially, your emotions stem from an interpretation of those perceptions. It isn’t you feeling stressed that causes your palms to sweat or your heart rate to increase. It’s your perception of that high heart rate and sweating that leads to your emotions of stress.

While this theory does seem to have positive therapeutic applications, the explanation itself to me seems to simplify or dismiss a key part of the emotional response cycle.

If we’re being chased by a bear, for example, our adrenaline response causes an increase in our heart rate, muscle tension, and several other physiological responses. But for those responses to be triggered, some part of our brain must have recognized the negative impact the bear can have on our survival and human experience, which seems to make emotion precede the physiological response.

The entirely opposite theory — that physiological states arise entirely from emotional states — also seems lacking concerning key aspects of emotions. Namely, certain phobias and conditioned responses.

Emotions as information

A third option, the evaluative theory of emotions, seeks to address these issues. According to this theory, emotions are an evolutionary shortcut to provide you with useful information about the world in a more readily available manner than conscious thoughts.

Pain is one such key emotion, providing us with a metric of where we’re hurt and the extent to which we’re damaged. The worse the damage, the more pain we feel. And the more pain we feel, the more the body’s physiological responses are heightened to react appropriately.

Emotions appear to be a progenitor of a feedback loop, giving us initial information and activating physiological responses that serve as a further source of information to our cognitive, conscious minds.

But while this was all good in early human periods, it has left us in quite a predicament in the modern world.

With the advent of new technologies, we’ve taken control of the evolutionary arms race, using our specialized brains to push ourselves beyond the bounds of natural selection. But despite creating all this technology, our brains are evolutionarily much the same as they were at the beginning of the homo sapiens era.

While this may not seem as big of an issue immediately, it becomes clear why it is an issue when we consider that our early human ancestors were often able to deal with and eliminate their sources of negative emotion with a level of immediacy that we cannot.

The parts of the brain activated when we have tight deadlines are the very same pathways activated when our ancestors were chased by tigers. But while you could run away and escape a life-threatening situation, you can’t exactly force that deadline to approach you sooner, leaving your brain in an emotionally heightened state for a prolonged period.

Wouldn’t it be so much easier to turn off the amygdala or at least limit its ability to control us? Well, here’s the thing, with today’s technology, we actually can. If we wanted to, we could turn off the amygdala, and we’ve done it in a few cases already.

Life without emotion

Using genetic and surgical modifications, we can selectively activate or inhibit neurons, pathways, or entire brain regions.

Studies doing this in mice have found that emotional responses to fear, anxiety and aggression were greatly inhibited, making mice more exploratory, curious, and socially peaceful.

But along with these seemingly positive impacts came a whole host of issues associated with the elimination of emotional responses. For one, a lack of fear response makes individuals extremely susceptible to environmental risks and life-threatening injuries. Consider, for example, if you saw a snake and were not perturbed by it. You might recognize logically that it could seriously harm you, but without a fear response, you have no reason to remove it.

But most perplexing is the inability of individuals or creatures with sufficient amygdala damage to do just about anything voluntarily. It isn’t that they are physically unable. Rather, without the amygdala, creatures seem to lack the motivation to carry out goal-directed behaviours, even ignoring basic survival drives like hunger and thirst.

In a particular study on mice, amygdalar damage led to the mice not pursuing or chasing food despite immense hunger, even though they were not restricted in any manner and could move about as they pleased. Unless the food was placed directly against their mouths the mice did not consume it.

Emotions play far more important roles in our daily lives than we seem to think.

Actions require emotions

For one, our base survival instincts are not logic, they are emotion.

When you cook and eat food, you’re not motivated by an entirely rational series of steps. The path of I am hungry, therefore I should get food and eat it is derived rationally, but the initial motivating point of hunger is a feeling, not a logical thought.

But suppose survival is preserved and we turn off the rest of the amygdala; are there any detriments then?

Consider what happens once survival is taken care of. Suppose you have all the money you could ever need and no longer need to do anything to guarantee your survival. What then?

Logic here doesn’t seem to say anything about that. Without an emotional basis, you can’t “want” to do anything at all.

It seems, then, that any action requires emotion to be initiated.

Emotions still suck

Emotions, both good and bad, can still be overwhelming. Every high seems to carry the seeds of a future low. The clichéd response is that you can’t have the good without the bad, and it’s true. The amygdala isn’t just about fear — it helps us experience joy and connection too. Without negative emotions, we lose the positive ones as well.

Sometimes, though, the good doesn’t seem worth the bad. Everyone’s approach to this will be different, but one idea that resonated with me comes from Eckhart Tolle in The Power of Now.

He explains that there’s a distinction between our thoughts, feelings, and the consciousness that experiences them. You aren’t your emotions or thoughts — you’re the observer. By recognizing this, you can become more present, especially when you aren’t in an emotionally charged state. Try it now. Take a breath, focus on it, and ask yourself, “What’s my next thought?” Then observe it without judgment.

No matter how hard we try, emotions will always be an essential part of the human experience. But being present, and being able to separate your conscious awareness from the pain and your constant thoughts is the key to living in harmony with them, without fighting or forcing them away.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.