We choose one and lay the blame on him,

put him away, make him pay the price.

And it may very well be just to do so.

But keeping ourselves open just a little

to the role we ourselves had to play

in creating the conditions for this outrage

may keep our ethical eye from going blind.

___________________________________________________

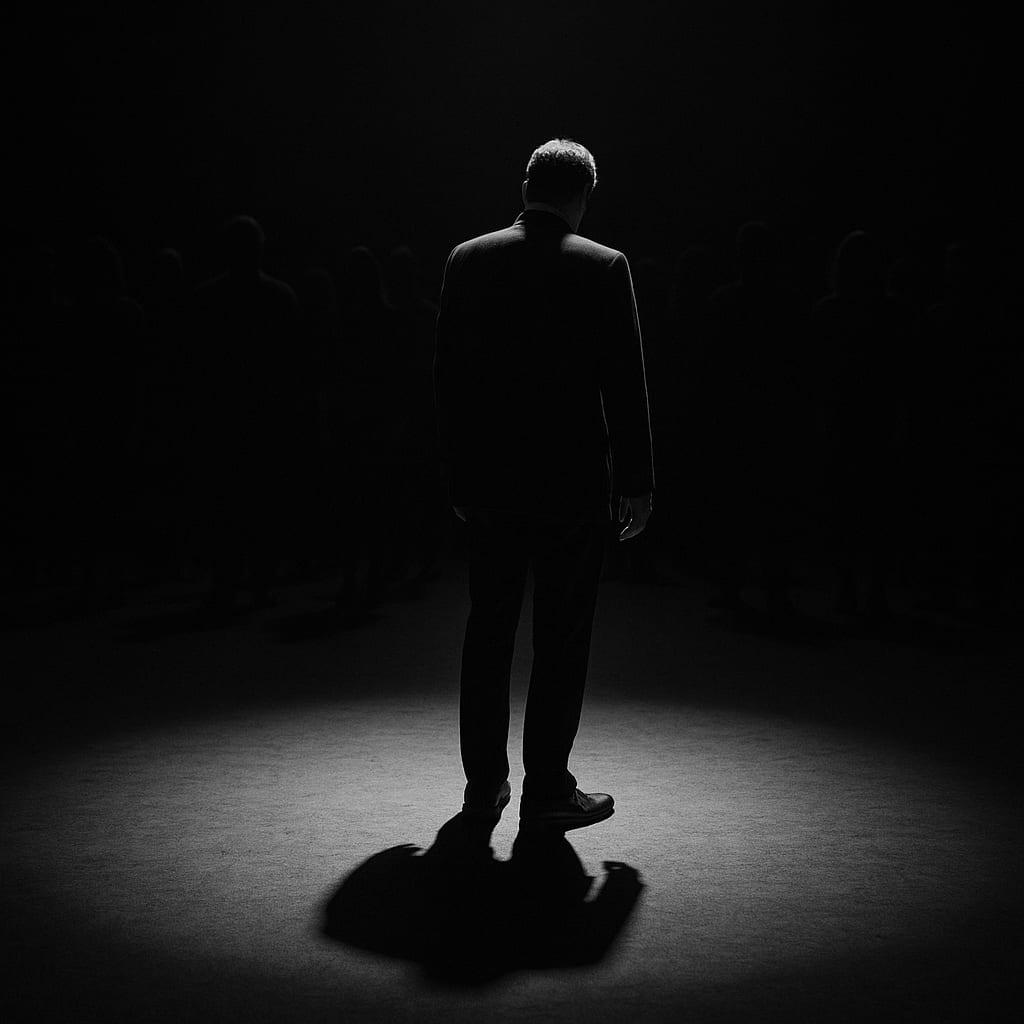

We crave villains because they simplify chaos. But blame shrinks truth, turning systems of harm into a single face. Real clarity begins when we resist convenience and widen responsibility.

___________________________________________________

When a corporation collapses or a government bungles a crisis, the public quickly settles on a villain. A CEO gets paraded before cameras, a minister run out of town, a celebrity shamed for their offense. For a brief while, it feels like justice. The world seems to make sense again because we pinpointed the person who was to blame.

This is way too simple. It lets us imagine that evil is located in one place, when it’s actually threaded through the systems, incentives, and silences that made the “bad actor” possible. As Hannah Arendt said, evil is less in the villain than in the banality of the arrangements that enable him.

Language plays its role in this process. Words like “monster” or “traitor” feel cathartic, but they distort complex humans into cartoons. The violence here is metaphorical, but real: calling people monsters whitewashes the conditions that made their behavior ordinary. By concentrating all our disgust in one direction, our language disguises the uncomfortable truth—that entire organizations, communities, or nations participated in the evil, either by commission or omission.

Even mere insults say more about the thrower than the target. “Coward,” “fool,” “loser”—these barbs mirror the speaker’s own fears and insecurities. To study a culture’s preferred insults is to study its anxieties: Americans obsess over “losers,” the British fear “fools,” authoritarian regimes scream “traitor.” The target could be almost anyone, but the echo always returns to the same place.

If we stop at the scapegoat, we stop short of truth. Real responsibility asks harder questions: Who built the stage on which this person performed? Who wrote the rules, who took the profits, who looked away? Who laughed at the joke before it curdled into cruelty? To widen the circle of accountability is not to excuse the wrongdoer but to reject the convenience of pretending that wrong is ever isolated.

Orwell famously warned that corrupt language shrinks thought. The same is true of blame. By making a single villain our target, we shrink our moral imagination. It is harder work to resist that convenience, to see that responsibility always ripples out beyond the single accountable individual. It is shared by all of us in ways we prefer not to notice.

We may never give up the convenience of finding a villain—it is a human reflex, ancient and satisfying. But justice is not the same as satisfaction. The work of repair begins when we look past the villain and examine the arrangements, the language, and the habits that let him flourish.

To do that is to trade convenient blame for inconvenient truth—the beginning of moral clarity.

About the Creator

William Alfred

A retired college teacher who has turned to poetry in his old age.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.