The Apartment Where I Learned to Be Alone

No one is disposable.

This is the apartment where I learned to be alone. There’s a big difference between living on your own and being isolated-amongst-people-alone. Covid-19 hasn’t been my first quarantine, and it’s not the first quarantine for many disabled and chronically ill folx. The first quarantine many of us experience is one that our body starts us on, and our relations seal us into.

Most folx with chronic illness will tell you that an unfortunate side effect of becoming sick is that your relationships are tested just as much as your body is.

When you get sick there is a mourning that happens. You are forced to change and adapt, and there is a loss of “my old self”. And for many there is a constant fight for access to good care, access to greater quality of life. And it becomes exhausting. You only have the energy for relationships that also have a return on investment.

I was watching myself grow sicker by the day. I couldn’t do things like walk the dog, or sit a long time, or keep up with many household chores. Errands were a big deal. Friends stopped inviting me to things because they knew I couldn’t do them. But they also didn’t plan things I could do either, or include me regardless. I wasn’t included in the group chats anymore. I faded from existence but I was still in my apartment.

So much so that my classmate Jeremiah said, “oh my God I thought you graduated!”

When I met a new student for the first time she said “You’re like a legend here, they talk about you and like, laud you but I was starting to wonder if you actually existed.”

How do you respond to that?

My friends whittled down to two people on campus. But my internet friendships were rich.

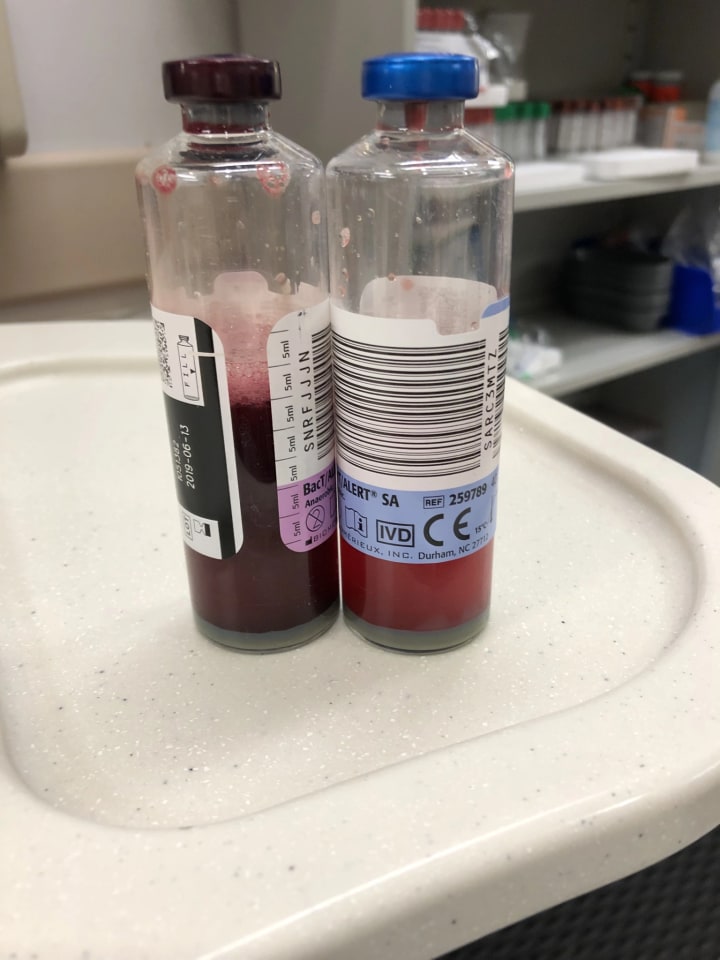

One day I woke up in horrific pain. My doctor told be I would be through most of it by the end of the weekend. But it never stopped. It became an unrelenting journey to find relief, to find answers, to find who I was before. All the while my life as it was before was dissipating around me. I had missed two weeks of class and if I didn’t return I would fail, lose my scholarship, and have to leave school. Two professors were willing to accommodate me- I was in so much pain I could barely sit down. They laid out a plan to take my coursework online, and they only needed the Dean’s approval.

She wouldn’t give it. She said “we would have to create a whole separate course for you that the registrar would have to put you in and that is just not possible.” The professors told me to do my work at home and they would accept it anyway. They didn’t want me to lose my presidential scholarship because of my health.

Since Covid-19 has progressed, my grad school has gone completely online. Converting all those in-person classes to online versions in a matter of hours and days. They’ve even had the audacity to publish a posting about “accessible worship” when neither of their chapels on campus is accessible to those with mobility issues or mobility aids. After three semesters of being denied accommodations, fighting for formal accommodation at a school and a consortium with no disability officer and no disability services, having the same Dean tell me I was not allowed to work my service dog in her classroom, and then force me to preach standing up when I was not physically able to do so (against my accommodations) I was livid. And I am not the only one.

Imani Barbarin has said that most disabled folx don’t become activists because they want to, but because they have to to exist.

And there couldn’t be truer words. Covid-19 has proven that our communities can be accessible, and easily so, you just have to do it. I never thought so much of my activism would simply be convincing people that would should care about others.

No one should get so sick that people walk away.

No one is too sick for love.

Disabled people shouldn’t have to be good at quarantine.

No one should be a ghost in their own life.

Disabled people are not disposable.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.