The World as a Window

Parajanov, Sayat-Nova, and the Outer Fringes of Cinematic Narrative Art

"In this healthy and beautiful life my share has been nothing but suffering. Why has it been given to me?"— The Color of Pomegranates (1969, inter-title)

The color of blood-red seeping pomegranates animates a film so strange, so thoroughly adapted to the interplay between subconscious thought and dream, that it makes the efforts of Jodorowsky, Buñuel, Fellini, and David Lynch seem like conventional, bourgeois entertainments by comparison.

Indeed, to clarify: it was the late David Lynch who observed that his life's journey as a filmmaker began when he decided that he wanted his "paintings to move a little." Today, in the age of AI-enhanced imagery, that is commonplace; but Lynch proved himself truthful with such early tableaux as Six Men Getting Sick, a sculptural art installation of six nauseated heads with images projected onto them, depicting them as vomiting and erupting in flames (the soundtrack was simply an insufferable alarm).

The Color of Pomegranates, a film by Sergei Parajanov—a brilliant, apparently troubled man (no less by Soviet censors), whose life and work remain deeply obscure to the West—is a film with no conventional narrative structure. It follows, in a very vague sense, the life of the Armenian troubadour Arutin Sayadian, or "Sayat-Nova" (literally, "The King of Song"), who died at the hands of Persian invaders while ensconced as a devoted brother at a monastery in 1795. During his life, he had a doomed love affair with Princess Anna, but ultimately, he returned to monastic life, having been raised in a religious setting.

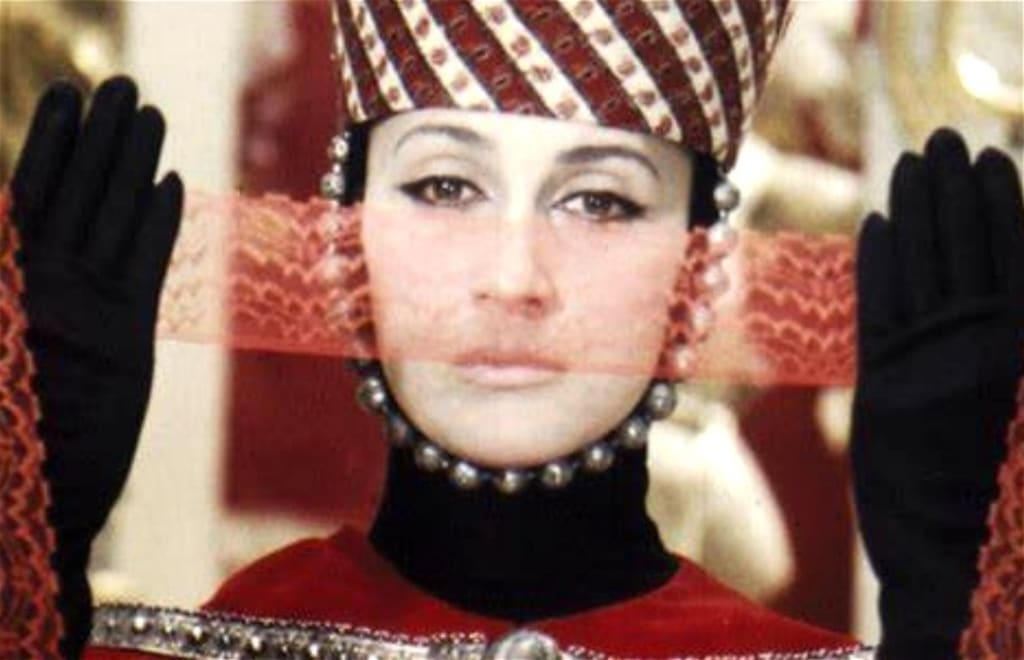

The film unfolds as a succession of posed scenes, displayed with a painterly eye, akin to the hyperrealist school of artistic expression. Actors are stiff, inanimate puppets; it is as if Parajanov, much like early Lynch, wanted to capture not movement, but the raw composition of a painting—only assuring that the viewer is jolted into a new awareness by the subtle, minimal movements of the various subjects.

Swimming up from the sea of metaphor, beyond the bleeding fruit (which functions as both religious and political allegory—revealing birth, death, and suffering in a liminal state of mixed interpretation), an early visual tableau, a dreaming image, shows the cherub-cheeked Little Sayat-Nova lying on the monastery roof, surrounded by books. This is a deeply literate film, with words being as central to its movement through the mausoleum of carefully constructed images as the inter-titles, which draw from Sayat-Nova’s own poetry, giving relevance—or at the very least, punctuation—to the rest of the film.

The books are lined up upon the roof (a metaphor for the poet’s mind or consciousness) while his dreaming young self imagines the worlds he will create within them, the words that will march up and down across the page—incantations and imprecations against a cruel and besotted world.

The World is a Window

The images are slow and ponderous, and the actors (if they can even be called that) function more as living exhibits. They move like battery-operated toys in a department store diorama, their small, strange, subtle gestures—a flick of the wrist, an arm raised to cover the face with a traditional Armenian cloth—depicting sacred imagery. Men bathe the mud from their bodies, washed clean of the turgid filth of sin. Graves are dug; animals are killed and skinned, to be devoured. Princess Anna brings red lace to her face; she embodies desire, but the sacrament of sex will be rendered dark and defiled against the poet’s skin, even as blood paints him in hallowed, redeemed red.

"The world is a window," the inter-titles lament. "And I am tired of these arches."

A mourning party beats a drum and carries the litter of a deceased nun. Earlier, a priest—or perhaps a bishop—lay in state, surrounded by sacrificial lambs, who climb the stone stairs upward, ascending symbolically toward a heaven they can never actually know. The face of the Blessed Virgin falls from her place on the ceiling of a forgotten chapel, one that may exist only in the poet’s sleeping mind.

In the final image, the young Sayat-Nova is elevated, holding two false wings, one in each hand, lifted by a visible rope. A false ascension; a phony miracle.

Sayat-Nova is doused in blood at the end, by a woman as cryptic and inscrutable as Princess Anna. Who is she? Why does she represent Death to him? Above, a man appears to be dipping his hands into a pot of sewage. Sewage seems to seep from open pipes below a platform. Has Sayat-Nova been absolved of his sin, or simply swallowed by filth? The film ends with the profile of the woman who showered him in blood. And it ends abruptly, without explanation.

A skeleton key would be required to truly unlock the deep cultural and historical significance of the imagery. An understanding of the ashugh, the life of the ancient Armenian troubadours, and Armenian culture in general would help. But, in a sense, that knowledge is unnecessary for the Western viewer, who can still appreciate this window into the subconscious—a series of sepulchral and holy gallery pieces that, as David Lynch might put it, "move a little." (Martin Scorsese is also a great admirer of the film.)

The restored version, available on YouTube, is an uncommonly beautiful spectacle. It is also an incredible film to hear—the clash of avant-garde elements, musique concrète sounds, wailing prayers and holy chants, and the traditional strains of Armenian music creating a disorienting blend of sound—sometimes punctuated by deep, pregnant silence.

Most will recoil when tasked with watching this film. But then, most will not find Fando y Lis, Begotten, Un Chien Andalou, Meshes of the Afternoon, or Eraserhead to their liking either.

But some will see that the window of dream is wide open here. And some will peer through, at first with curiosity, but then with admiration and love.

The Colour of the Pomegranates | Sergei Parajanov | 4K | Subtitled | Original name: Sayat-Nova

Connect with me on Facebook

My book: Cult Films and Midnight Movies: From High Art to Low Trash Volume 1

Ebook

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments (2)

Great article, Tom. I'm watching the movie now.

good story