🤖 The Scars of Progress: What the 'Retirement' of Figure 02 Tells Us About Humanoid Robots in the Factory

After 11 months on the BMW assembly line, Figure AI's humanoid robot has been 'retired,' providing invaluable, gritty data on the reality of real-world industrial deployment.

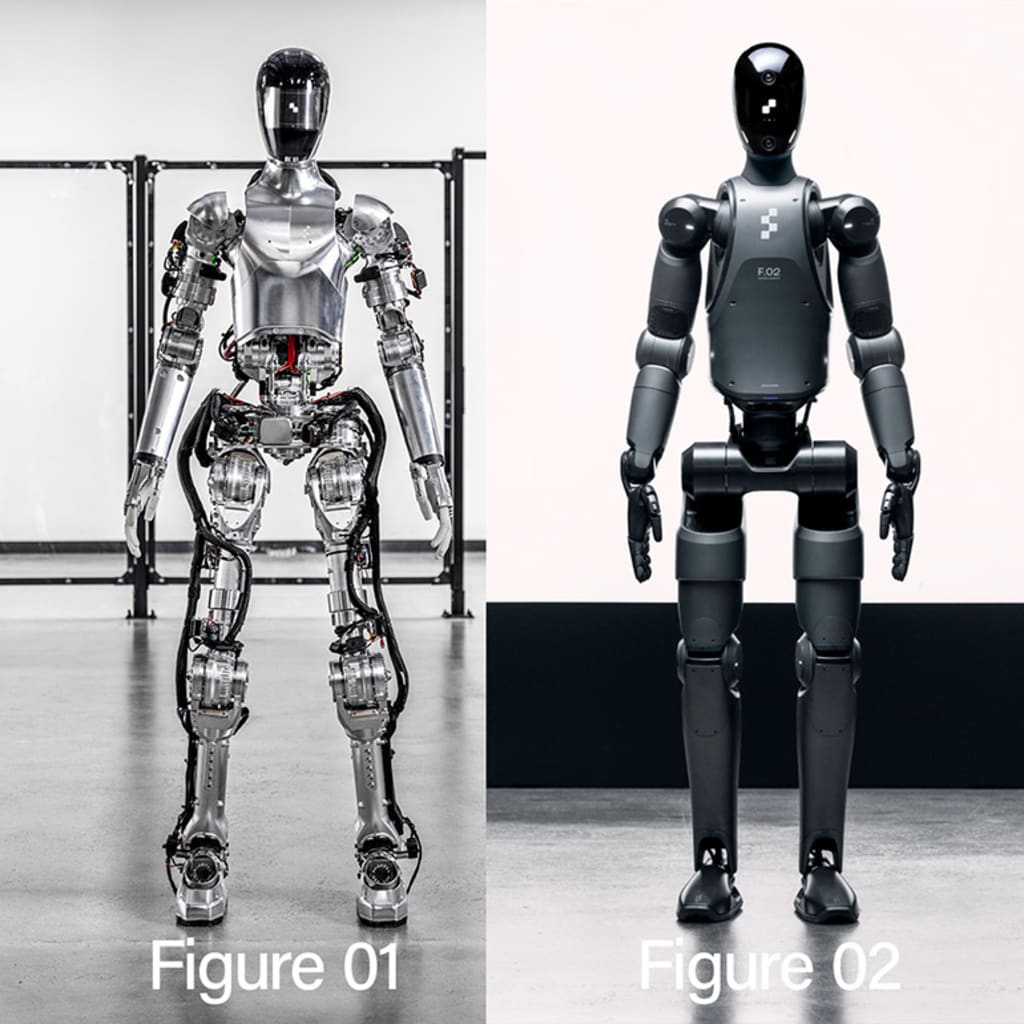

n the relentless march towards fully autonomous factories, the announcement this week that Figure 02, the humanoid robot from Figure AI, has been officially "retired" after an 11-month deployment at the BMW manufacturing facility in Spartanburg, USA, is far more significant than a simple press release. This isn't a failure; it is a monumental success story in data collection, marking a crucial inflection point in the development cycle of real-world humanoid robotics.

CEO Brett Adcock’s shared image of Figure 02—scuffed, scratched, and visibly worn from its tenure—is perhaps the most honest piece of evidence we have seen regarding the integration of bipedal robotics into heavy industry. This robot didn't operate in a pristine, controlled lab environment; it worked side-by-side with humans, tackling the grime, dust, and unexpected variables of a high-volume automotive assembly line.

The Spartanburg Deployment: A Crucible for Bipedal Design

The partnership between Figure AI and BMW was never just about replacing human labor; it was a sophisticated, high-stakes testing phase. The goal was to prove that a general-purpose, bipedal humanoid could perform a variety of non-specific tasks in a pre-existing, non-robot-optimized environment.

Figure 02 was tasked with several roles, likely including logistics, picking and placing components, and basic assembly tasks. The 11 months Figure 02 spent at the BMW plant acted as a crucible for its design. Every scratch on its chassis, every minor repair, and every software glitch provided Figure AI’s engineers with proprietary, real-world data that cannot be replicated in a simulation.

Key Takeaways from the Wear and Tear:

Durability Validation: The visible scratches and wear confirm the robot's physical shell and joint mechanisms were subjected to significant stress. This data is essential for redesigning parts to be more impact-resistant, dust-proof, and resilient against common industrial hazards.

Thermal and Power Management: Operating continuously over several shifts in a factory environment—which can fluctuate widely in temperature—stresses battery life and heat dissipation. The 'retirement' suggests the current iteration has gathered enough data on optimal power cycling and cooling needs under constant load.

Software and Perception Tuning: Humanoid robots fail not because of physical weakness, but because of errors in perception and decision-making. The real data on mispicks, navigation errors, and interactions with human workers will be invaluable for fine-tuning the robot’s advanced neural networks and visual processing capabilities.

The Mismatch: Humanoid vs. Fixed Automation

One of the great debates in industrial automation is the necessity of the humanoid form. Why build a complex, bipedal robot when simpler, fixed-arm automation (like traditional KUKA or FANUC robots) is often faster and cheaper?

The answer lies in flexibility and generalized intelligence. Fixed automation is excellent at one specific, repetitive task. Figure 02, however, represents the first generation of robots designed for general-purpose reasoning. It can theoretically be taught a new task through simple demonstration or natural language commands, requiring no physical re-tooling.

The 'retirement' of Figure 02 signals that the first generation has served its purpose: gathering the environmental data necessary to bridge the gap between lab-perfect motions and real-world industrial tolerance. The next iteration, presumably Figure 03 or a revised 02, will be informed by the practical limits found on the BMW floor, possessing greater autonomy and robustness from day one.

Ethical and Economic Implications of the Pause

This "pioneering phase" is critical to understand the long-term economics of this industry. Humanoid robots are extremely expensive to develop and currently cost far more than human labor over a year. Their economic viability relies on two factors:

Cost Reduction: Mass production, informed by this real-world testing, will drive unit costs down dramatically.

Generalization: The ability to move the robot from a logistics role one week to an assembly role the next, without significant re-engineering, maximizes the return on investment.

The decision to retire Figure 02 is a strategic pause, not a defeat. It means the company has collected the maximum amount of valuable gritty data and must now translate that wear-and-tear into better, more reliable hardware and smarter AI for the next generation. The scratches on the robot are, in fact, the most valuable data points they possess.

Conclusion: The End of the Beginning

Figure 02’s 11-month service at the BMW plant should be viewed as the end of the experimental phase and the dawn of industrial standardization for humanoid robotics. The visible signs of battle—the scuffs, the dings, the fatigue—are the true measure of its success. They represent a million tiny, complex interactions with the messy, unpredictable world of a functioning factory.

The next generation of Figure robots, built upon the hard-won data of Figure 02’s service, will be more capable, more resilient, and more poised to transition from being an industrial experiment to an indispensable part of the global workforce. The future of manufacturing just received its most valuable performance review.

Comments (1)

tks!