Sanity in Stitches

A story of modern hand embroidery

It could be said that I have become an award-winning internationally recognized artist because of peer pressure. And because I used to live in a van.

I was pretty sure hand embroidery was not for me before I even knew what it was called. My friend sat with a threaded needle and a piece of fabric pulled taut in a hoop one summer afternoon and told me I should try it. “You would love it,” she assured me, “it’s just like painting but with thread.” It was a lightweight, portable, inexpensive hobby I could fit into a bag. Perfect for my setup in a converted minivan while I roadtripped the United States.

A few days later she handed me my very own starter set: two hoops, a couple of fat quarters (pre-cut cotton fabric), some needles, and a selection of embroidery floss. Special scissors—sharp, small, sewing scissors—were also essential, but I already had a pair because I love scissors and was not exactly new to fiber crafts; I already crocheted.

She instructed me on how to set up the hoop, tugging on the edges of the fabric while slowly tightening the metal closure of the hoop. It’s ready when it’s tight like a drum. Cutting a length of red floss, I threaded my needle and stared at the empty hoop. “What do I do?” I asked blankly.

“Anything you want.”

“There’s no special stitches or anything?”

“There are some knots but you don’t need those. Just tie the end and start drawing with the thread.”

My hand behind the hoop, I poked the needle through the fabric at random. Transferring my hand to the front of the hoop, I pulled the needle up until the thread caught, then pushed the needle down again. Very clumsily, I made a basic flower.

Dopamine. Happy brain soup.

I stared at it with pupils dilated. Suddenly I could see the entire hoop filled with a rainbow of flowers. Green stems would be added last, after I had tried out every single other color. I could picture it so clearly that it did not occur to me to draw out the idea, on the fabric or otherwise.

Hand embroidery is slow going, even for the experienced stitcher. My little flower design took days to finish—and I worked on it for hours each day. I was completely obsessed. All I could think about was embroidery. The pop of the needle going through the fabric and the little hiss of the floss being pulled. Up, down, up, down. Thread knotted on purpose; thread knotted by accident. Sharp scissors snipping ends.

I was devastated when I finished the piece.

What now? My hands, so recently busy, were still and empty. My mind, so calm and engaged when I stitched, was unfocused and reaching. Quick, think of something else to stitch. Sunset. Go.

For the rest of the summer, I went over to my friend’s home nearly every evening to stitch together. We curled up in her bed, turned on Downton Abbey, sipped whiskey, and embroidered. From flowers and sunsets, I moved on to tide pools and a toad with flowers instead of spots. I learned about Joann’s craft store (how had I never been there before?) and went with her to pick out more fabric, more thread, hoops in different sizes. I cut up a cracker box to make cardboard bobbins to wind my thread on so it wouldn’t get tangled in its zip lock bag. I started following other embroiderers on social media.

Soon, I learned that hand embroidery was an ancient artform with a rich history. Far from my Wild West approach to stitching—just stabbing it until it gets prettier—there were established techniques, even names for all the stitches. An entire world of art was opening for me. The slow, tactile process appealed to me like no other craft I had ever tried. My finished pieces grew in number, my techniques improving quickly.

A successful full-time artist friend of mine studied my finished embroidered pieces and startled me by asking if she could buy one of them. I laughed uncomfortably and told her she could just have it. Looking up, she said, “This is really good. You have moved past craft, here. You’re making art.”

My hobby was certainly increasingly valuable to myself, taking up larger and larger portions of my brain and life. I began to consider it as I looked ahead, trying to see where I could fit it into my future. I knew I had discovered something special and important.

I did not know that in addition to stitching art that summer, I was also stitching my safety net and the hem of my sanity.

One year later and my choices for the day came to this: I could sit at home cuddling my new dog, trying to numb my mind via binge-watching television, or I could voluntarily go be traumatized with a small group of relatives while we watched as someone we love suffered. I stood in the kitchen, staring vaguely around, before wandering into the living room. Looking at the couch as if I had never seen it before, my attention drifted to the liquor cabinet. It was only ten in the morning. I turned away. In my new shared studio/office space, I tried to think of something to do. If I were to leave, I would need something to do with my hands. No way could I face sitting in a hospital room or waiting area with nothing to do. My eyes fell on a black dress in a grocery bag at the bottom of the closet.

It had been ugly when it came to me but had fitted well and the tags were still on it when I had pulled it from the trash bag of clothes. I had already removed the brooch, ruffled collar, and sash. Now it was plain, sleeveless, gathered at the body and then flaring at the skirt to a high-low hem. I had intended to decorate it.

The dress was transferred a canvas tote. Looking around, I found my tiny, zippered bag. Inside was a tin that used to hold mints but now held sewing needles, a pair of sharp sewing scissors, and a bag for thread scraps. I added a bobbin of white embroidery floss to the zippered bag and closed it. The last thing I needed was a hoop. I selected one with a six-inch diameter and put it in the tote.

Coping bag was packed. Now to go endure.

My grandfather did not look like my grandfather anymore. He had aged a hundred years. Always very tall, he was now shriveled and small. His glasses and teeth had been removed, making his face seem sunken, unrecognizable. Well, the parts you could see behind the machines. They beeped and whirred and buzzed and puffed, a disconsolate symphony keeping his body alive. My eyes flicked to the purple band on his arm with the letters DNR: “Do Not Resuscitate.”

Relatives gave taut smiles and subdued waves as I tiptoed into the room. The lights were off. After whispered greetings, I sat down and pulled open my bag. My craft felt like my own life-saving machine, there for keeping my broken heart brave enough to stay in the room. Twisting the metal clamping device on the top of the embroidery hoop, I loosened it, pulled the inner hoop away, and settled the dress inside it. I wanted to hand embroider this methodically, from one shoulder, around the neck, and ending on the other shoulder. Pulling out the bobbin of embroidery floss, I measured the length of my arm and cut. Embroidery floss is made of six strands of thread. Using all six strands of floss felt too heavy-handed for this project, so I separated them, threading my needle with two strands instead.

What to stitch?

I kept my eyes on the blank stretch of fabric; this room would offer me no inspiration. I knotted the tail as I considered. This project felt important, deeply significant in a way I could not yet articulate. Something to make me happy. I needed to stitch something to make me happy. Flowers, a trailing vine, and little decorative knots wound their way across the neck of the dress in my mind’s eye. Without sketching my ideas or taking the time to plan anything at all, I stuck my needle through the back of the fabric and began to stitch.

I only worked on the dress when I was near my grandfather. It took weeks; I could not make myself go up there every day. Each stitch was threaded through my heart. He was moved to a different hospital, and again. Each clipped thread felt like another of his lifelines severed. I showed up with my canvas bag, sat down, and tried to disappear into the stitches.

Life moved on, inside and outside of the hospital. He sometimes made progress. I remember when he was well enough to sit up and eat some pudding. But we were at the long, very draw-out ending of his life, and at some point, I realized I was embroidering the dress I would wear to his funeral.

The dress was finished in September. I wore it in the first week of October to the one bright spot in a miserable season of my life. My embroidery had been juried into an art exhibition for the very first time. I felt relieved that the dress had a moment to shine, to be art on an artist at an art show. Another artist even complimented me on it. I clung to my plastic wineglass.

Two weeks later, I got The Call. Dropping the rag, I left a sink of soapy dishes.

I did not make it in time.

Leaving the dishes where they were, I drained the cold water when I got back.

For three days I didn’t get out of bed. On the fourth day, I went through photos of my grandfather. In one, he smiled at the camera, wearing a green plaid shirt. Perfect. I had never done a hand embroidered portrait before, but I needed to do one now.

Studying the photograph, I carefully selected the colors. I made a design based on the photo, transferred it to the fabric, and stretched it into a hoop. With my little tin of needles and my special scissors, it all went into my canvas tote. My coping bag continued to serve its purpose: I brought it with me and stitched my grandfather’s portrait as I helped to plan his funeral. This project was more peaceful. Each stitch was love, another memory committed in thread. Each trimmed thread helped me to release him, thankful for the time we did get to share.

When it was finished, I painted with watercolor around his head. Green, to match his shirt. After it dried, I mounted it onto a canvas, stretching it tight and sewing the fabric edges together on the back. I took pictures and shared them on social media. One of my relatives called. “Oh my god,” she whispered, “it looks just like him.”

There was a request to display it at the funeral.

I wore my black dress, embroidered with white flowers and so many hospital moments; my art dress for an artist, here to deliver art.

His portrait was the start of a series. Several faces and six months later found me sat at the doctor’s office. “I’m going to go ahead and start prepping you for surgery,” the doctor informed me. Her tone was calm, and she was smiling, neither of which could be said about me.

“Surgery?” My mind seemed blank, filled with a buzzing static. I had only come in to have a scan read. I was in my twenties. I had been living in a minivan driving the USA five minutes ago.

“Yes, in two weeks. I’m just going to go ahead and do the pre-op work now,” she said. “We need to get this out. It might be cancer.”

I was still mostly bedridden when we got the pathology report back. It was not cancer, but a progressive inflammatory disease that caused internal bleeding. Based on what had already been removed, I had stage III of a rarer form that had infiltrated my organs, spreading scar tissue and disease growths. While there is no cure, there was a solid chance of going into long-term remission. Another surgery would be needed, this time by a team of specialists.

My health, which had already been in decline over the last two years, seemed to give out. I struggled to function, just trying to take care of myself enough to make it to the next day. The disease caused widespread pain, including nerve and joint pain, extreme fatigue, migraines, gastro issues, trouble sleeping, swelling, and a host of other symptoms.

I put myself on the five-month wait list to meet the first specialist, went gluten-free and vegan, bought a TENS machine, and tried to remind myself every single day that my suffering was (hopefully) temporary.

Hand embroidery was now vital to my survival. I set goals: By the end of the year, I wanted to have my work in six exhibitions, published in two different publications, and to have myself juried into a modern embroidery art organization.

The corkboard above my worktable was filled with ideas: watercolor experiments, neon threads, diagrams of stitches I wanted to learn, portraits waiting to be started. Unable to do much else, the work I loved filled my days. When I could not sit up in a chair, I would bring the hoop and thread to the couch. As I started to struggle with losing the feeling in my legs, I kept my hands even busier. I received and completed my first portrait commission, and then my second.

I was so proud to meet my embroidery goals. My body was failing but I kept on stitching. To my delight, I succeeded in making it into half a dozen exhibitions. My publishing ambitions were also realized. From my sickbed, I saw my work in magazines and newsletters distributed from Europe and Australia. After much agonizing over an artist’s statement, I applied to the modern embroidery group. I cried when I was accepted. I was an actual artist in real life. Look—this group of people said so!

In a year during which I did not seem to exist as a person, my art was flourishing.

Finally, one year after my first surgery, it was time for the big operation. Five pounds of disease growths and scar tissue was removed from twelve areas of my body, including my kidneys and intestines. My appendix and the entire inside wall of my abdomen were removed. There had been so much scar tissue that the organs in my abdomen had been cemented together. But they had been able to remove every sign of disease and that was paramount for my chances of going into remission.

Following the operation, I could not walk unassisted for three days. The pain was brutal. It would be three months until I saw any progress, I was told. Full recovery would take a whole year.

Two and a half weeks after the surgery, I was off the pain medication and back on my favorite drug: hand embroidery. I could not sit up in chairs for more than a few minutes, but I practiced everyday while I stitched. It was slow, slower than before, but it was also the best work I had ever done.

My physical healing seemed mirrored in my art journey.

It was three months before I regained basic function. I could finally comfortably sit in the car or in a chair and walk for more than a few steps. We had also sorted out my post-op care of taking drugs five times a day and how to live on an anti-inflammatory diet (see also: eat kale and suffer).

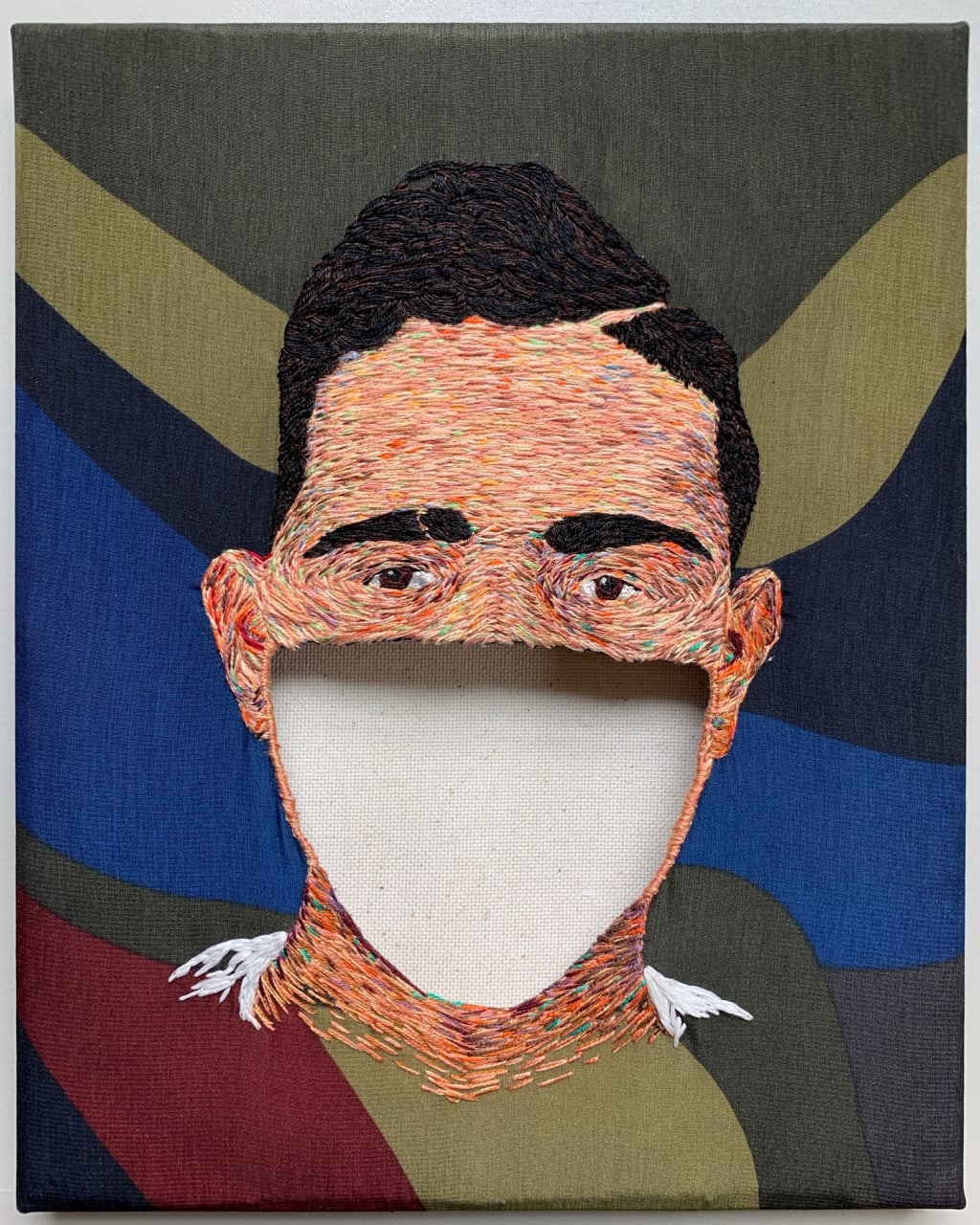

During those three months I worked on a risky, experimental piece. I embroidered a face but the area from the nose to the chin—the area normally covered by a pandemic-style face mask—was (carefully, so very carefully) cut away. The portrait was then mounted on a backward canvas so that a cavity was made in the art. When you looked at the face, you could see through it to the canvas underneath.

At the six-month mark, I started to have more days without pain than in pain. It was right around Christmas, and I felt like my body was gifting me signs of returned health. We discussed starting to reduce my medications. My embroidery became more inventive and incorporated different types of threads and unusual tools: I stitched the face of a political figure, cut it out, then stitched it to a flyswatter.

Nine months after my surgery, my hair changed texture. Having never been a fan of my aggressively straight hair, I was indecently excited to achieve my childhood dream of having princess hair. My locks were now decidedly wavy with some curls. This change is an uncommon, but not unheard of, body response to the surgery. It seems to confirm that the disease was indeed fully removed—a good sign for hopes of remission. When my hands weren’t fussing with my new hair, I was pushing my needlework. I stitched my first greyscale portrait and studied color theory and creativity.

One year after the operation, June 2021, and I am considered healed. What a journey. My energy levels have risen dramatically, and I feel confident about moving on with my life in remission. My embroidery has become more inventive. I dream bigger, have pushed my goals. The first piece I stitched after my big surgery was juried into an international show in Ukraine. My art is going to Europe for the first time! My greyscale portrait won an award. I was interviewed on an art podcast.

What started with a single stitched flower on my friend’s couch became a lifeline during heartbreak and illness. Humble tools found in every home¬¬—needle, thread, scissors—held my life together like a spun cocoon. I am reborn: healthy, award-winning, internationally exhibiting, great hair. I look around my dedicated studio space now and can hardly believe I used to do this in a minivan. To be fair, I had far fewer thread bobbins back then, and I don’t keep them in zip lock bags on cut up cracker boxes anymore.

I talked on the phone yesterday to my friend who introduced me to embroidery. I asked if I could meet her in Italy. Rome, to be exact, over the last week of October. That embroidery group I worked to get into is having an exhibition there and I just found out my art will be included.

Thank goodness this did not turn out to be an inexpensive hobby that wouldn’t take up too much space. An entire world of art is opening before me.

About the Creator

Courtney Cox

Published author and award-winning internationally recognized modern hand embroidery artist

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.