Rooted in Light: The Biophilic Vision of Binh Nguyen Duc

How a Los Angeles–based designer fuses leaf‑vein algorithms, quantum‑computing lobbies, and half‑million‑dollar courtyard sculptures into spaces that listen to nature’s intelligence

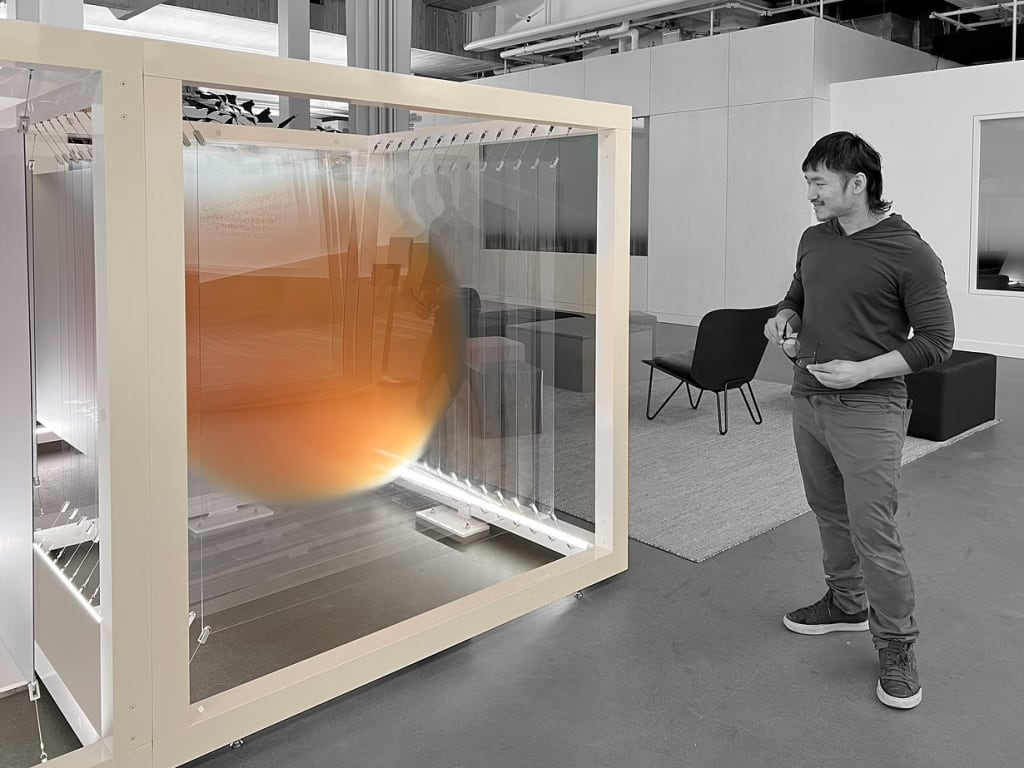

Binh Nguyen Duc operates at a rare intersection where the primal rhythms of the natural world merge with the precision of advanced technology. A Los Angeles–based artist and architectural designer, his decade‑long practice spans immersive 3D installations for quantum‑computing lobbies, half‑million‑dollar courtyard activations on research campuses, and brand‑defining environments for entertainment and life‑sciences agencies. For Binh, design is not about spectacle—it is an ongoing dialogue. “Absorbing all relevant context, not getting sidetracked from the big picture of what’s at stake, and preserving the purity of the design idea,” he explains, guides every decision, from the vein patterns he traces in leaf venation to the collaborators he chooses to translate vision into form.

He begins each project not with blueprints but with an impulse. “If a design idea excites me in its spatial look and feel,” he says, “or its behavioral impact toward users, then it may have legs.” That spark might come from observing the vein pattern on a ficus leaf, recalling the mist rising in a redwood grove, or remembering how the sun glints off wet stones at dawn. For Binh, these are not mere inspirations. They are templates, the original algorithms of structure and light. He treats them as equal partners to the computer-aided tools he wields, and they guide decisions that range from materials to scale.

One of his most visible recent works stands in a lobby dedicated to quantum computing, its form an abstract botanical sculpture of shimmering metal filaments. It is an homage to a cluster of coastal live oaks that once thrived near Stanford’s campus, their twisting branches compressing into a design so subtle that visitors only notice its organic qualities upon closer inspection. “Nature is infrastructure,” he says. “It is the first engineer.” He designed the sculpture with that in mind, using parametric modeling to capture the oaks’ branching patterns, then collaborating with master metalworkers to hand-finish each node. What emerges is neither a literal tree nor a conventional art piece, but a living conduit—part scientific diagram, part whispered memory of place.

That balance between art and science extends to his brand activations for research campuses and luxury retail flagships alike. For a Southern California life-sciences institute, he created a half‑million‑dollar courtyard installation that simulates the ebb and flow of a desert wash. Walls of layered sandstone and terrazzo undulate like shifting dunes, while integrated lighting triggers in sync with sunrise and sunset. He describes the project as an exercise in “parallel storytelling”—one narrative drawn from the region’s geology, the other from the institute’s mission to accelerate discovery. The effect is elemental and immersive: visitors move through the space as though tracing a riverbed in slow motion, their footsteps echoing off stone and light.

Binh’s own path, he recalls, was never a moment of sudden revelation. After earning his architecture degree, he spent six years in New York on short-term gigs that taught him the limits of conventional design. “Not being able to land a full‑time offer,” he remembers, “pushed me to define my own artist statement.” During that period, he rejected buzzwords like “experiential marketing” in favor of a more rigorous, context-specific approach. When a gallery asked for a simple pop-up exhibit, he proposed instead a series of modular pods inspired by seed pods, each housing a miniature ecosystem. The client balked—but when visitors responded with wonder at the tiny ferns and live moss, Binh knew he had hit on something essential: design that speaks first to the senses, then to the mind.

That sensorial honesty underpins his critique of today’s design landscape. “We often overemphasize flashy gadgets,” he says, “and forget that the best experiences are full-body encounters.” His aversion to trend‑driven spectacle extends to the much‑touted world of artificial intelligence. He uses Midjourney and Stable Diffusion to generate quick mood boards, calling them “virtual cloud visualization printers,” but he insists they cannot replace the collaborative choreography required to build a physical space. “AI’s language is copy and replicate,” he explains, “but it cannot innovate in context.” Instead, he reserves his trust for engines like Unreal and Lumion, which allow him to convey spatial atmospheres with a fidelity that clients can almost touch through the screen.

Yet even these digital tools bow to nature’s authority in Binh’s view. When he advises emerging designers, he offers no secret recipe, only a gentle reminder: plant your seed and listen. “Working with nature is a one-way street,” he says. “Give it sun, air, water, and it will grow.” If there is “growth difficulty,” he warns, it signals that conditions must be adjusted—whether in site analysis, material choice, or fabrication methods. His own studio embodies this ethos: a living laboratory where rare aroid plants perch on worktables, their sculptural leaves mirroring the forms he sculpts in metal and resin. Next to them rest gemstone specimens—quartz, chalcedony, moss agate—that Binh regards as snapshots of the earth’s history.

Teaching has become another vital dimension of his practice. At the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and later at the University of Calgary, he saw students as “oracles of future reality.” He recalls a thesis project that fused playground design with early‑childhood development research—an approach he calls “visionary simplicity,” where straightforward forms encourage complex interactions. “Their bravery and carefree attitude,” he says, “accelerate us practitioners exponentially.” In those classrooms, he learned that mentorship is not a one-way street; he left as invigorated as the students he guided.

And yet, for all his curiosity, Binh remains anchored in humility. When asked what fuels his relentless experimentation, he answers simply: love. “We are offspring of nature,” he says, “and creativity is the purest form of translating the endless current of love in this life.” He carries that current into every collaboration—whether with glass blowers, structural engineers, or biologists—each brought in not for prestige but for their unique gifts. “True partnerships,” he insists, “emerge when a problem calls for a shared solution.” He cites Olafur Eliasson, the Danish‑Icelandic artist, as a guiding influence—“a father figure in biophilic art”—but he stresses that it is the quiet alignment of vision, not celebrity, that drives real innovation.

As we close this chapter of study, Binh’s gaze turns skyward. He speaks of a dream installation that would draw on his recent fascinations—time travel, black holes, the corona of the sun—melding earth’s elemental intelligence with cosmic wonder. Yet even this grand vision remains tethered to his guiding maxim: “Art first, technology second.” In Binh’s hands, a final work would not be a monument to novelty but a sacred communion with nature’s intelligence, a space meant to reconnect us—to our origins, our emotions, and the endless current of love that flows between them.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.