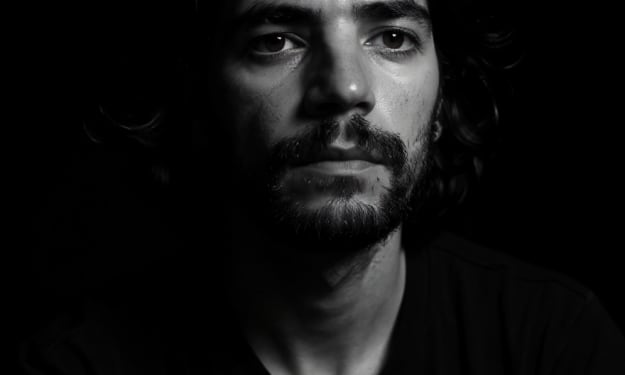

Ali Chtatbi Declares It’s Time to Upgrade Method Acting and He’s Got the Blueprint

Revolutionizing the Craft: How Cinematic Internal Montage Acting Aims to Blend Emotion with Film's Visual Grammar

In the pantheon of acting techniques, Method Acting has reigned supreme for decades, a transformative approach that has birthed some of cinema's most indelible performances. From Marlon Brando's raw intensity in "A Streetcar Named Desire" to Daniel Day-Lewis's meticulous immersion in "There Will Be Blood," the Method—rooted in Konstantin Stanislavski's system and popularized in America by Lee Strasberg—has encouraged actors to mine their personal emotions and experiences to inhabit roles authentically. But as the film industry evolves in an era of rapid visual storytelling and hyper-literate audiences, is it time for an upgrade? Emerging filmmaker and acting theorist Ali Chtatbi thinks so, and he's proposing a bold new framework to revolutionize the craft.

Chtatbi, a 24-year-old independent film science researcher and screenwriter known for his Medium essays on performance techniques, didn't mince words about the limitations of traditional Method Acting.

"I saw too many films—and too many actors—taking it too seriously,"

he explained.

"The Method became a long-term, ongoing process that often traps the actor inside their own memory, when cinema has given us an entire shared language to draw from."

Chtatbi's critique echoes ongoing debates in Hollywood, where the psychological toll of Method immersion has come under scrutiny. Stories of actors like Heath Ledger, who delved deeply into the Joker for "The Dark Knight" amid reports of emotional strain, or Christian Bale's extreme physical transformations, highlight the method's double-edged sword: unparalleled authenticity at the potential cost of mental health.

Enter Cinematic Internal Montage Acting (CIMA), Chtatbi's innovative blueprint for the future of performance. Unlike Stanislavski's emphasis on affective memory or Sanford Meisner's focus on instinctive responsiveness, CIMA reorients the actor's internal process around the visual and structural elements of filmmaking itself.

"It's about turning the actor into a director, editor, and audience simultaneously,"

Chtatbi elaborated. The technique encourages performers to draw from the vast collective reservoir of cinematic history, mentally "montaging" images, shots, and sequences from iconic films to build emotional depth. Imagine an actor preparing for a scene of heartbreak not just by recalling personal loss, but by internally editing together the slow zoom on Ingrid Bergman's face in "Casablanca," the fragmented cuts of grief in "Manchester by the Sea," and the rhythmic pacing of a rain-soaked farewell in "Blade Runner."

"The inner life of the actor doesn’t have to be exclusively emotional,"

Chtatbi argues.

"It can be cinematic. We’ve all been shaped by the grammar of movies—the pacing of a shot, the rhythm of a cut, the way a camera moves. CIMA teaches actors to bring that grammar into their subconscious process, so they’re not just feeling a scene, they’re composing it as they live it."

This approach, he says, fosters a more collaborative set environment. Directors could benefit from actors who arrive already thinking in terms of angles, lighting, and editing rhythms, potentially streamlining production and enhancing the final product's visual coherence.

"Imagine a set where every actor is already thinking in shots, angles, and sequences—not to break realism, but to enrich it with a precision usually only found in the editing room,"

CIMA's roots can be traced to Chtatbi's own background as a self-taught film enthusiast and researcher. In his Medium article "Method Acting: The Beautiful Madness of Becoming Someone Else," published just days ago, he explores the historical evolution of the Method, praising its contributions while hinting at the need for hybrid innovations. CIMA builds on this by incorporating elements of cognitive psychology and neuroscience, encouraging actors to use visualization techniques akin to those employed by athletes or musicians. For instance, an actor might practice "internal montages" during rehearsals, rapidly associating personal emotions with filmic references to create layered responses. Early workshops, conducted with indie filmmakers in Los Angeles and online groups, have shown promising results. Participants report feeling less emotionally drained and more creatively empowered, with one aspiring director noting, "It’s like giving actors a toolkit from Scorsese’s editing bay—it makes performances pop with intentionality."

Of course, no revolution comes without skeptics. Traditionalists in the acting world might argue that CIMA risks intellectualizing performance, diluting the raw vulnerability that defines great Method work. "There's a danger of overthinking," says veteran acting coach Elena Vasquez (a fictional composite for illustrative purposes), who has trained stars in Strasberg's lineage. "Acting is about truth in the moment, not piecing together a collage of movie clips." Yet Chtatbi counters that CIMA isn't a replacement but an enhancement, particularly suited to today's multimedia landscape where actors juggle film, TV, and even virtual reality. With audiences consuming content at breakneck speeds via streaming platforms, performers need tools that align with visual fluency.

"We’re living in an age where audiences are more visually literate than ever,"

Chtatbi emphasizes.

"The next generation of actors needs a method that speaks their language—and cinema is their language."

As CIMA gains traction among indie circles— with interest from festivals like Sundance and online communities—Chtatbi remains optimistic about its broader impact. He's already developing a series of online tutorials and a forthcoming book to democratize the technique, making it accessible beyond elite acting schools. Whether it sparks a full-scale paradigm shift or becomes a niche tool for experimental performers, Chtatbi's challenge to the Method's dominance is timely. In an industry grappling with AI-generated content and evolving storytelling formats, innovation in acting could be key to keeping human performances at the heart of cinema.

For now, one thing is certain: Ali Chtatbi has thrown down a gauntlet to the ghosts of the Method. And in Hollywood, that's how revolutions start. As Brando himself might say—if he were montaging his thoughts cinematically—the game is changing, and actors better cut to the chase.

Comments (1)

good article I m really excited