TO SINK AND PLUNGE ONESELF IN ART

How it feels to be in the Sistine Chapel Exhibit x Sounding Grainger

The word immerse comes from the Latin root, immersus: "to plunge in, dip into, sink, submerge."

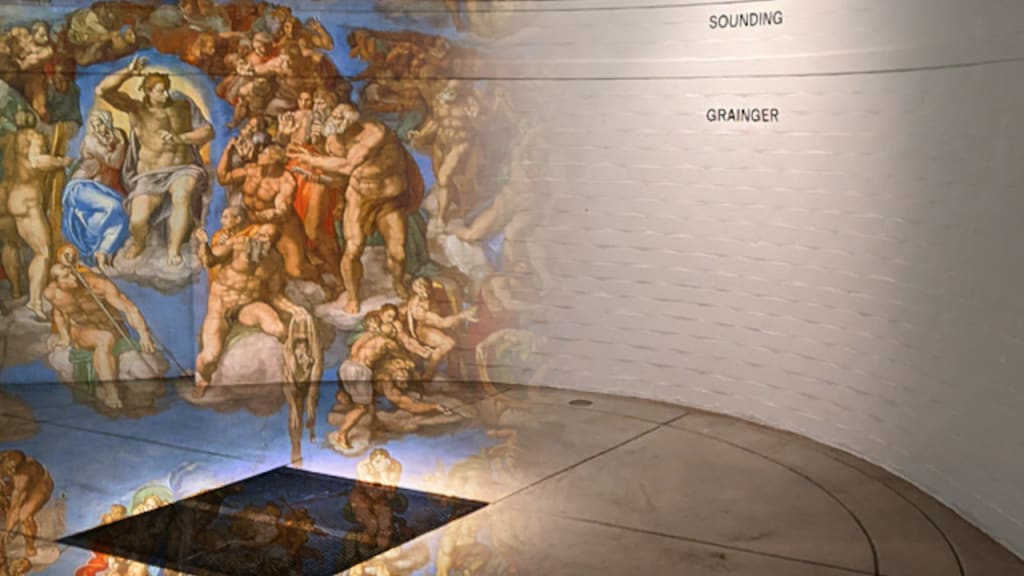

The Sistine Chapel exhibition, held in the Emporium Melbourne, and the Sounding Grainger exhibition, in the Percy Grainger Museum at the University of Melbourne, are two exhibitions which demonstrate the increasing rise of the immersive museum exhibit. What is it like to be immersed in experience? Let’s find out.

In the Sistine Chapel exhibit, the immersion is marked by the shift in light. From the stark, bright exterior of the Emporium shopping centre I descend into the darkened, dramatic space.

The lighting is dimmed in parts, and the giant panels depicting the bodies are lit up from beneath, as if it were a stage. Alongside these monumental bodies, in this world of floating clouds and biblical mythology I wander, completely displaced from reality, in reverie and splendour. It is as Robert Desnos writes about being fully immersed: “the room and the spectators disappear… transported to a new world compared to which reality is but a charmless fiction.”

The clarity and colour of Michelangelo’s monumental bodies are breathtaking. The scale recreates the artist’s proximity in the process of creation: I too, am close enough to breathe life into his work, brushstroke by brushstroke. Through the audio-guide’s narration, details in the paintings leap out. The artworks in the assembled chapel are larger than life and cinematic in scope. Sophistication is signaled by the elegant baroque chamber music that resonates in the background, re-injecting the grandeur of Michelangelo’s legacy in this artificial, contemporary space.

I take the next photo just after I see an influencer pose in front of Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, arms akimbo, gaze defiantly meeting her companion’s camera lens. She has her back to the work, without a single glance at what she stands in front of, before slipping out of the exhibition. I ask myself, how much can one see, without looking?

By way of contrast, it is sound which illustrates the lived landscape in Sounding Grainger.

At the beginning of the exhibition, I come face to face with Rochus Hinkel’s audiovisual installation, depicting the astral image of the building itself.

The menacing soundtrack holds me captive as I witness the building’s complete disintegration. Two others are watching alongside me, but leave before the presentation is finished. “It’s fantastic!” someone says to their companion as they proceed to explore the building. I can’t help but feel as if they have missed out on something. The explosive finale to the audiovisual installation is arresting, and uneasiness pervades as it restarts. Hinkel describes it as the burning down of a museum which “rises from the ashes.” After completing a circuit of the museum, re-watching the audiovisual causes me to identify with the spaces that I see. Knowing the topography of the museum, the second time the museum burns down, it feels as if I am going down with it.

Walking the empty halls of the building, I am invited to haunt the long corridors of the architecture, alongside the ghost of Grainger himself. Each room paints a different picture through its soundscape: I pause to listen, and there being nothing before me, it is in my mind’s eye that I see.

The few objects in the museum include a piano, and one of the machines that Grainger himself created. It is enormous, foreboding, and retains his idiosyncrasy.

Gazing upon it conjures its whirring, hissing, clicking, and snarling, invoked by the soundscape that surrounds me. With so few objects in the museum left to look at, the bare, sweeping curves and archways of the white walls within the museum beg you to inhabit them, to follow the lines that they draw and seep into their smallest corners. It sounds different there.

*

The immersive exhibit allows us to experience art in a different way. The philosopher Gaston Bachelard describes this as a “chrysalis.” He writes that the chrysalis, as a notion, “bespeaks both the repose and the flight of being.”

What I think he means is, we are fully tapped into a bodily experience, but explore not as ourselves. At once, we are in the space, immersed by the art, and at the same time, far away in the depth of our experience. When it is over, we carry it with us: our immersion, encapsulated.

*

Thank you for reading! Please follow for more content like this.

All photos used in this article are mine.

More information about the exhibits:

About the Creator

Christina

ARTIST / CURATOR / RESEARCHER

I research immersion and co-creativity through an auto-ethnographic approach. When I'm not researching, I create worlds I hope you'll enjoy too. Explore my art on instagram: @kuri--hime @calmesvibes

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.