The Roads Between

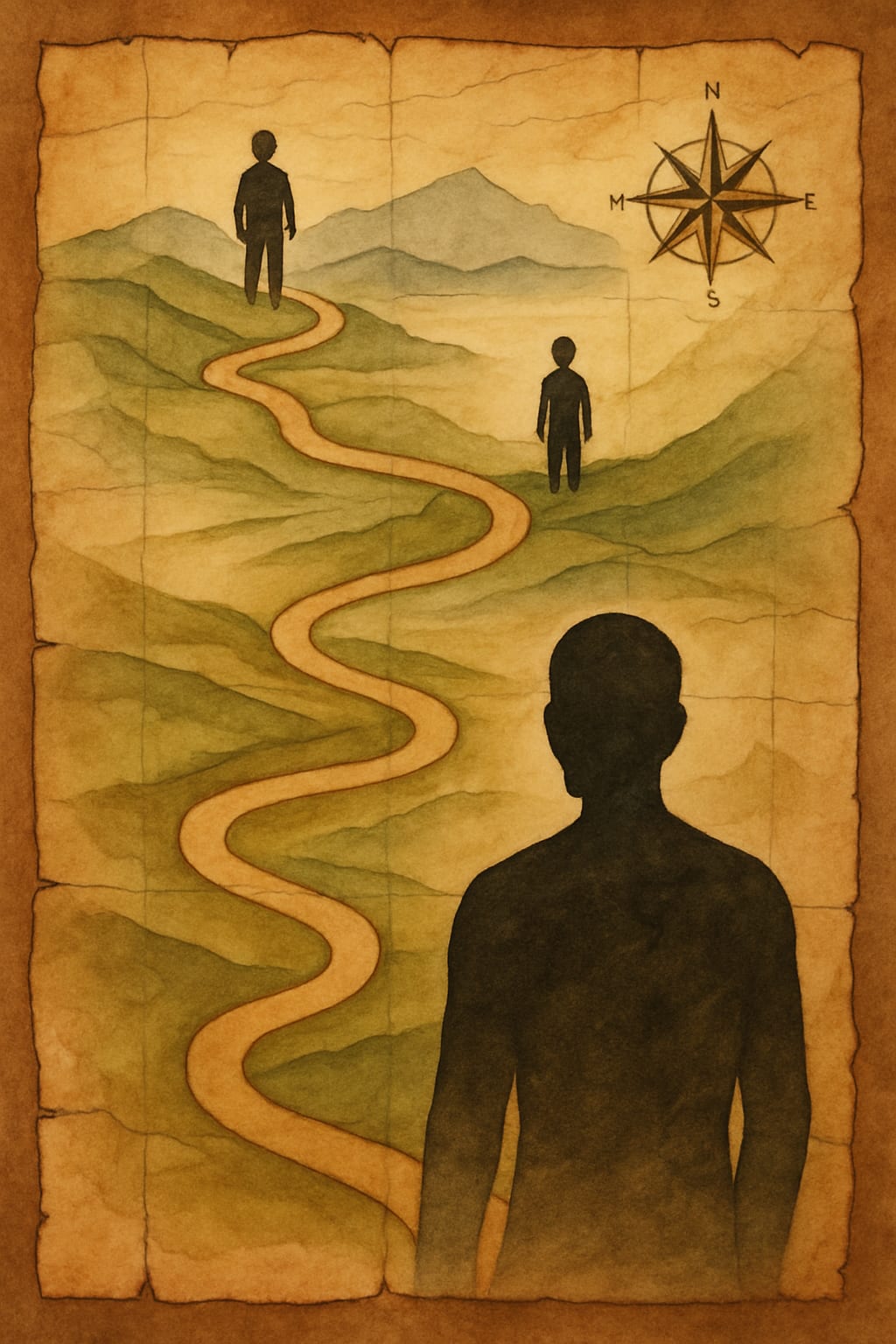

Journeys across the selves I’ve inhabited

If I were to unfold a map of myself, it would not resemble the geographies of the earth. No rivers, no capitals, no mountain ranges marked by surveyors. Instead it would hold a series of shifting territories, each one belonging to a different version of me — territories sometimes linked by fragile bridges, sometimes separated by impassable ravines.

It is not one country, but an atlas. A book of maps I carry inside, even when I try to forget the weight of it. The paper is fragile. The ink changes color depending on how I remember. Some pages are smudged, some missing. But the atlas is there all the same.

This is how I read it.

The Child: The Village of First Light

The first territory is small. A village drawn with bright markers and uneven lines, as if a hand too young to master the pen sketched it in haste. The houses are square, the doors wide, the trees lollipop-green and perfectly round. The proportions are wrong, yet in their wrongness, they feel truer than any adult cartography.

In this village, the distances are deceptive. The walk from my bedroom to the kitchen is an expedition. The path to the garden gate, a pilgrimage. And the tree in the yard — clumsy trunk, sprawling branches — feels taller than any cathedral.

Here, roads are paved not with asphalt but with feelings. The hill of Fear rises sharply whenever I must walk alone down the hallway at night. The River of Curiosity cuts through the village, widening each time I touch something I was told not to, each time I ask one more question. And always, in the distance, the Mountain of Wonder gleams: the unreachable sense that the world is vast, enchanted, impossible to exhaust.

The Child’s village is both tender and cruel. There is no scale, no compass. Joy and terror have the same address. Every door opens into eternity, but eternity may last only an afternoon.

When I look back now, the village is still intact. Time has not razed it. It waits in me, folded, patient as an old photograph.

The Adolescent: The Labyrinth City

Flip the page and the lines sharpen. The next map is sprawling, tangled, scribbled over in pencil and then erased. This is the city of my adolescence.

Its streets coil like snakes. Some end abruptly in brick walls painted with graffiti no one can quite read. Others open into vast plazas that echo with emptiness, no one daring to linger too long. Every corner hides a new disguise. Every building seems under construction, half-finished, half-abandoned.

The city smells of smoke and iron. It hums with music that leaks from windows — half rebellion, half longing. It is crowded, yet the loneliness is overwhelming.

Here the cartographer was restless. Borders shift daily. A district once filled with friends can, overnight, turn into a wasteland of misunderstanding. The bridges collapse as quickly as they are built. Maps go out of date the moment they are printed.

I remember the constant searching. Every alley promised an exit, a way out of confusion, but often led me deeper inside. I was both explorer and prisoner of this labyrinth. At night, the city pressed close against my ribs, whispering all the ways I did not belong.

And yet — there were bright spots. A rooftop where the skyline cracked open just enough to reveal stars. A secret café where laughter broke through the walls of doubt. A door, always half open, into the unknown.

Adolescence is a city that teaches you to get lost. And getting lost, I learned, is another way of finding.

The Adult: The Archipelago of Roads

The third map does not show one landmass but many. A scatter of islands, some lush, some barren, some so small they disappear when the tide shifts. Ferries run between them, though not always on schedule. Bridges exist, but they are fragile, often swept away by storms.

This is adulthood: an archipelago of selves, each island a different version of the person I am trying to become.

There is the Island of Work, crowded with glass towers, the air full of deadlines. Next to it lies the Island of Solitude, where the forests are thick, the beaches quiet, and the only language spoken is silence. To the north, the Island of Desire, its shoreline carved by fire. To the south, the Island of Memory, where ruins of the Child’s village and the Adolescent’s labyrinth still rise, half overgrown, but unmistakable.

The seas between them are unpredictable. Sometimes calm, sometimes violent, sometimes stretching so wide that the next island feels unreachable. Navigation requires compromise: knowing which crossings are worth the risk, and which storms must be endured.

Unlike the earlier maps, this one acknowledges history. On the Island of Memory, I still see the crooked tree of my childhood yard. In the Labyrinth District preserved like ruins, the echoes of teenage voices drift. These places are not erased. They are layered. They remain in the atlas, folded over, part of the archipelago’s foundation.

And yet, adulthood carries its own cartographic trick: the illusion of permanence. The islands feel fixed, but I know they shift. Shorelines erode, new inlets form. The atlas of selves is never finished.

The Roads Between

If there is one feature that unites these maps, it is the presence of roads. They do not always appear on the page, but I know they exist — thin, invisible lines that link the territories.

A road runs from the Child’s village to the Adolescent’s city. It begins as a dirt path lined with wildflowers, then hardens into cracked pavement, then disappears into an underpass littered with echoes. Another road leaves the Labyrinth and reaches the Archipelago, but it forks constantly: one path leads toward responsibility, another toward escape, a third doubles back into memory.

Walking these roads is what makes the atlas coherent. Without them, the maps would remain fragments. With them, I see how each version of myself — fragile child, restless adolescent, uncertain adult — is not separate but connected, overlapping, haunting one another with continuity.

The roads remind me that I do not discard my former selves. They travel with me, folded into my steps.

The Atlas Still Unfolding

If I close the book now, I can hear the rustle of future pages. Blank maps waiting for their lines. Territories unnamed, seas uncharted.

Perhaps one day there will be a map of old age: a desert, vast and contemplative, its sands shifting with memory. Perhaps there will be another island, unexpected, where a new version of me builds a city with steadier walls.

For now, I live in the archipelago, navigating between islands, carrying the earlier maps in my pocket. I try not to forget that the Child’s village still stands inside me, its windows glowing. That the Adolescent’s labyrinth still hums with music, even if the streets are half-ruined. That every road I take now is drawn over paths I once traced in wonder, in confusion, in hope.

The atlas is not finished. It never will be. And that, perhaps, is its greatest truth.

To chart oneself is not to fix the world in place but to acknowledge its movement. To admit that we are made of territories both lost and alive. To unfold the maps we carry, and to walk their roads again — not to return, but to recognize.

So I carry my atlas. I trace the paths. I honor the ruins. And I wait, patient, for the next map to reveal itself, glowing faintly, already forming in the distance.

About the Creator

Alain SUPPINI

I’m Alain — a French critical care anesthesiologist who writes to keep memory alive. Between past and present, medicine and words, I search for what endures.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.