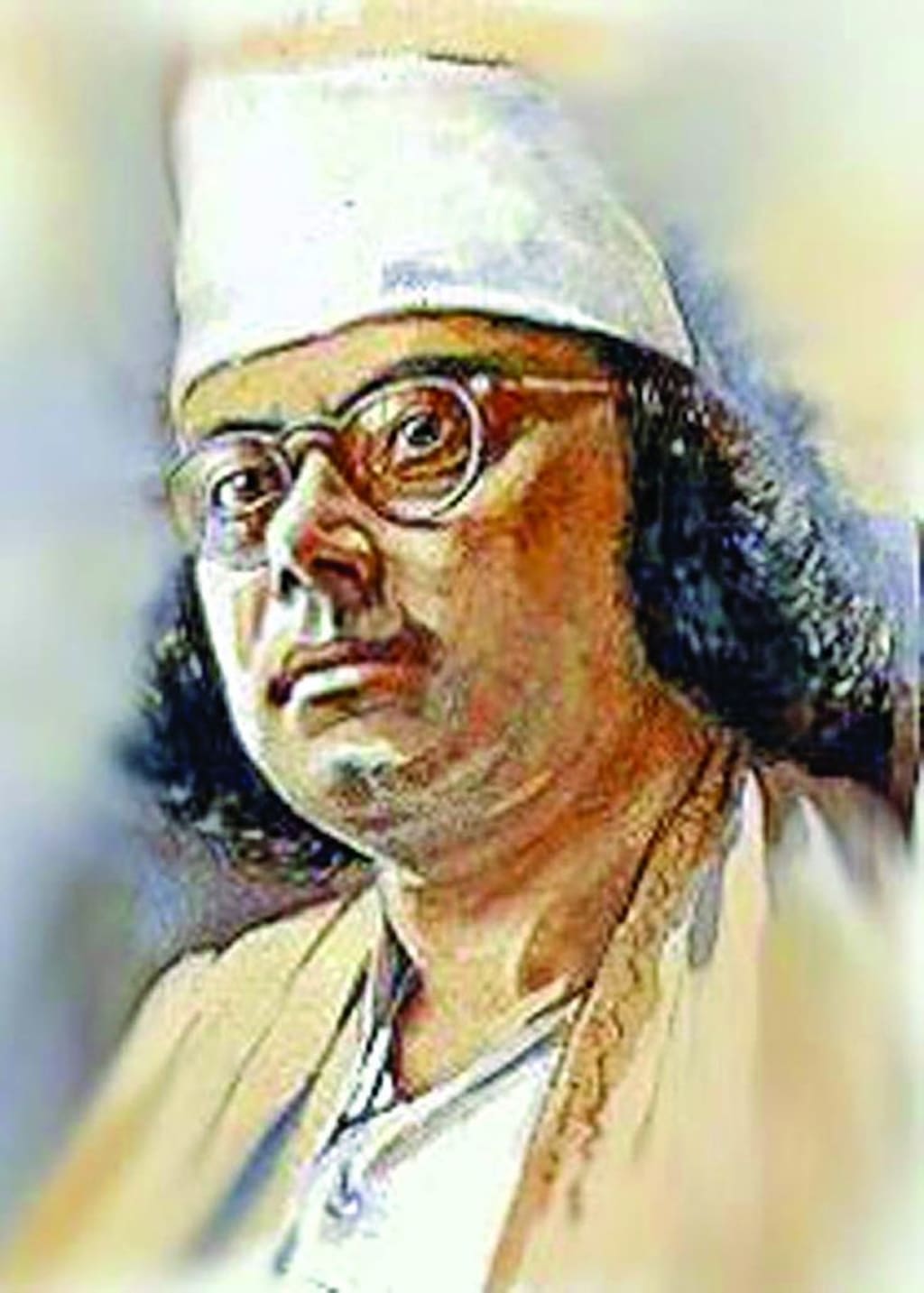

The Rebel Poet: Kazi Nazrul Islam's Journey from Struggle to Legacy

A Tale of Courage, Love, and Unyielding Spirit That Inspired a Nation

When a barefoot village boy from a poor Bengali Muslim family began singing in village fairs and acting in folk dramas to survive, few could have guessed he would go on to become the voice of rebellion for an entire nation.

That boy was Kazi Nazrul Islam—now remembered as the Rebel Poet, a man whose pen was sharper than a sword, and whose songs could stir both storms and souls.

A Child of Struggles

Born on 24 May 1899 in Churulia, a dusty village in present-day West Bengal, Nazrul lost his father at the age of nine. Poverty hit hard. To feed himself and support his family, he joined a traveling folk theatre group known as a "When a barefoot village boy from a humble Bengali Muslim family started singing at village fairs and acting in folk dramas to make ends meet, few could have imagined his journey would lead him to become the voice of rebellion for an entire nation. This boy was Kazi Nazrul Islam, who would come to be known as the Rebel Poet—a man whose words carried a power more potent than a sword, whose songs could ignite both storms and souls.

**A Child of Struggles**

Kazi Nazrul was born on May 24, 1899, in the dusty village of Churulia in what is now West Bengal. His life took a difficult turn when his father passed away when he was only nine. The weight of poverty pressed down on his family, pushing him to join a traveling folk theatre group, where he sang and performed just for a meal. Despite these hardships, Nazrul nurtured a fierce intelligence and a dreamer’s heart. While other boys his age might have been occupied with multiplication tables, Nazrul was immersing himself in Persian poetry and Hindu epics, fluidly moving between the Quran and the Mahabharata.

**The Soldier-Poet**

In his late teens, Nazrul became a soldier in the British Indian Army, serving as a Havildar during World War I. The barracks turned into his classroom, where he delved into philosophy, politics, and poetry. It was there that he found both his voice and a purpose worth fighting for. After returning from the war, he burst into Kolkata’s literary scene like a meteor. His iconic poem "Bidrohi" (The Rebel), published in 1922, stunned readers with its raw intensity: "I am the unutterable grief, I am the trembling first touch of the virgin, I am the throbbing passion of the heart of the young maiden..." His poetry was not merely words; it was a revolutionary movement in itself.

**The Voice the British Feared**

Nazrul’s writings sent tremors through the colonial authorities. His fiery essays and poems cried out for justice, freedom, and a future where caste, communalism, and colonial oppression were mere memories. The British responded swiftly, shutting down his newspaper "Dhumketu" (The Comet) and imprisoning him for over a year. Yet even from behind bars, his spirit shone brightly—he continued to write defiant poetry and fasted in protest, almost sacrificing his life, but his resolve never wavered. “My hands are tied, yet I write. My voice is chained, yet I sing.”

**Lover, Husband, Father**

Amidst the storms of public life, Nazrul found tenderness in his personal relationships. He married Pramila Devi, a Hindu woman who bravely defied societal expectations in 1924. Together, they welcomed four sons into their lives, but not without heartache—three of their children passed away young. His personal grief only deepened the emotional resonance of his poetry, where love and revolution often danced together.

**The Songsmith of the People**

Nazrul was not just a poet but also an extraordinary composer and singer, crafting nearly 4,000 songs known as Nazrul Geeti. He seamlessly wove together classical ragas with folk tunes, blending Islamic devotional songs with Hindu bhajans. He refused to be categorized—one day, he might write a ghazal in Persian style, the next, a Shyama Sangeet in praise of Goddess Kali. His central message was universal: humanity above all else.

**Silence and Legacy**

By the 1940s, as the world shifted with the tides of war and independence, Nazrul's own health began to fade. A rare neurological condition robbed him of his voice—the very weapon he had wielded with such power. By the time Bangladesh declared its independence in 1971, Nazrul lived in silence. However, in 1972, the Bangladeshi government honored him, bringing him to Dhaka and declaring him the National Poet. He passed away on August 29, 1976, resting beside the mosque at Dhaka University—a place where knowledge and youth thrive, and where his spirit continues to inspire.

**More Than a Poet**

Today, Kazi Nazrul Islam is not merely remembered for his poetry or songs but for his unwavering moral courage. He was the poet of rebellion, love, unity, and peace. He stood up for the oppressed, challenged injustice, and dreamed of a world where no one would be judged by religion, class, or gender. In every sense, he was a poet who truly belonged to a time beyond his own. As he once said, “If nothing else, let me live as a man, let me die as a man.” And in that, he absolutely succeeded. Letter dol", singing and performing in exchange for food.

Even as a child, he was a dreamer with fierce intelligence. When most boys his age were learning multiplication tables, Nazrul was absorbing Persian poetry and Hindu epics, moving easily between the Quran and the Mahabharata.

The Soldier-Poet

In his late teens, he joined the British Indian Army, where he served as a Havildar during World War I. In the barracks, instead of just marching drills, he devoured books on philosophy, politics, and poetry. In the army, he truly found his voice—and a cause worth fighting for.

After the war, he exploded into the literary scene of Kolkata like a meteor. His poem "Bidrohi" (The Rebel), published in 1922, electrified readers:

"I am the unutterable grief,

I am the trembling first touch of the virgin,

I am the throbbing passion of the heart of the young maiden..."

It wasn’t just poetry. It was a revolution in rhythm.

The Voice the British Feared

Nazrul’s pen terrified colonial authorities. Through his fiery essays and poems, he called for justice, independence, and a world without caste, communalism, or colonial chains.

His newspaper "Dhumketu" (The Comet) was shut down by the British. He was jailed for over a year. But even behind bars, he wrote poetry that glowed with defiance. He fasted in protest and nearly died. His spirit, however, remained unbroken.

"My hands are tied, yet I write.

My voice is chained, yet I sing."

Lover, Husband, Father

Amidst the storms, there was also tenderness. In 1924, he married Pramila Devi, a Hindu woman, who defied social norms of the time. Together, they had four sons, though tragedy followed them—three of their children died young. His personal grief only deepened the emotional depth of his writing.

In his music and poems, love and revolution danced side by side.

The Songsmith of the People

Nazrul wasn’t just a poet—he was a composer and singer of incredible range, creating nearly 4,000 songs, later known as Nazrul Geeti. He blended classical ragas with folk tunes, and Islamic devotional songs with Hindu bhajans.

He refused to be boxed in. One day he was writing a ghazal in Persian style, and the next day a Shyama Sangeet in praise of Goddess Kali.

His message was simple: humanity above all.

Silence and Legacy

In the 1940s, just as the world was changing with war and independence, Nazrul's health began to decline mysteriously. He was diagnosed with a rare neurological condition that gradually stole his voice—the very weapon he had wielded so powerfully.

By the time Bangladesh became independent in 1971, Nazrul was living in silence.

In 1972, the new Bangladeshi government brought him to Dhaka with honor and declared him the National Poet. He passed away on 29 August 1976 and was laid to rest beside the mosque of Dhaka University—a place of learning and youth, where his spirit still lingers.

More Than a Poet

Today, Kazi Nazrul Islam is remembered not just for his poetry or songs, but for his unshakable moral courage.

He was the poet of rebellion, but also of love, unity, and peace. He spoke for the oppressed, challenged injustice, and dreamt of a world where no one would be judged by religion, class, or gender.

He was, in every sense, a poet far ahead of his time.

“If nothing else, let me live as a man, let me die as a man.”

And that, he did.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.