The Fountain and Mayan Mythology

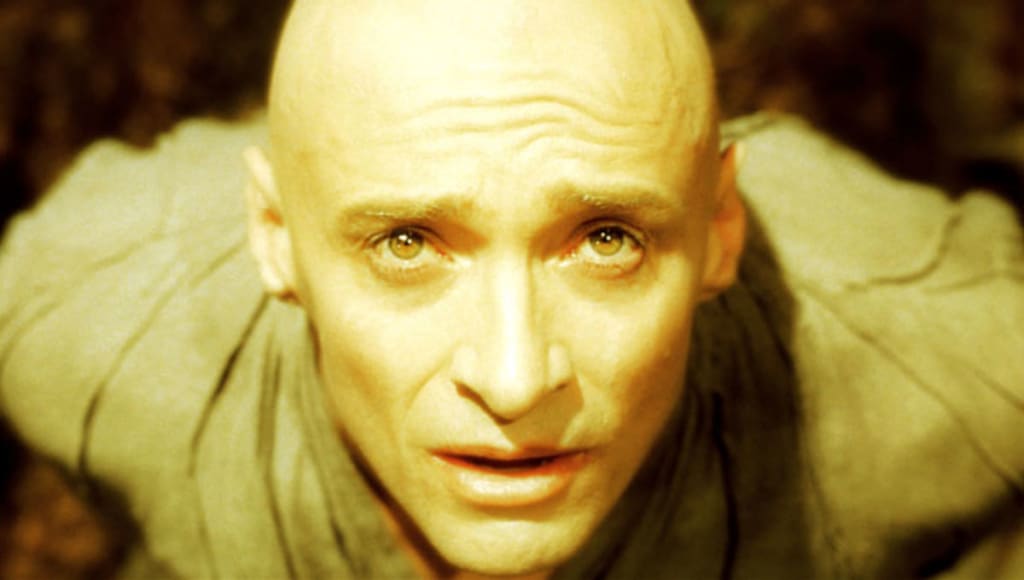

How film and myths can help us understand our own mortality

All humans want to extend the invariably short lives given to them, and the metaphysical, psychological, and cosmological insights provided by Hugh Jackman’s various characters and the Mayan stories of creation and Hunahpu and Xbalanque demonstrate that that belief is universal and crosses the boundaries of time and culture.

Our insights into the cultural and religious beliefs of the Quiché Maya come from the Popol Vuh, which translates to “Council Book” or “Community Book.” It is this book that preserves the recorded history and myths of this Mesoamerican people. The Fountain takes great liberties with the mythology for the purposes of its narrative.

For example, the Mayan Creation story, as told by Izzi in the film, stems from the death of the First Father, who, upon dying, has trees and plants and life spring from his body -- the first creation of life. This differs from the Mayan Creation story in the Popol Vuh, which does not begin with nothing, but with a sea and sky. There exists the primordial gods: Sovereign Plumed Serpent, the Maker, Modeler, and the Bearers, Begetters, and Heart of Sky. There is no mention of these gods in the film. The gods first create the earth, then the animals, but finally choose to create human beings to worship and praise them.

This took multiple attempts to accomplish. The Maker, Modeler attempted to carve humans from the wood of the coral tree, but they lacked the ability to speak and praise the creators, so they were destroyed in a flood. It was not until humans were made from the yellow and white corn that they were capable of worshipping the deities.

When the failed attempts at human creation are destroyed, their remnants today take the form of monkeys. The film potentially pays homage to this tidbit by having the neurosurgeons perform their tests on a monkey, relating the humans back to their failed first incarnations. The flood also draws a direct line back to the Mayan Tree of Life being associated with the Tree of Knowledge, as an almost exact story of destruction occurs in the Book of Genesis.

As the film states in its opening text, Genesis describes the Tree of Life as being guarded by a Cherubim with a flaming sword. When Tomás eventually ascends the steps of the Mayan pyramid where the Tree of Life supposedly resides, he is struck down by a Mayan priest wielding a flaming sword. This cross-contamination of religious storytelling is one way that the film highlights the universality of wanting to overcome death. In this instance, it speaks to this desire across cultural boundaries.

It is important to note that humans were formed from corn, maize specifically, a detail which gives an aetiological insight into Mayan culture. Maize was the staple agricultural crop in Mayan culture, and as such is considered a sacred source of food. The color of the maize is also important. The colors yellow (or gold) and white permeate throughout The Fountain. Gold is used to represent desires and goals. This is seen in Tom’s gold wedding ring, which he loses and constantly searches for, the gold hue of the research facility where he searches for a cure, the gold adornments of Queen Isabella, whom Tomás will wed once he completes his quest, and the gold of the Xibalba nebula that Space Tom travels toward. White represents the purity of life. Izzi is often seen in white. There is also a lot of freshly fallen snow, and the sap that Tomás eventually drinks from the Tree is pure white. In tandem, these two colors represent the desire or goal to preserve life.

The Fountain is also structured similarly to the Popol Vuh (and arguably, this essay). That is to say, paratactically, in which ideas are presented with no logically discernable connection between them. The creation of humans in the Popol Vuh is interrupted by extensive episodes about the Hero Twins and their achievements. The three sections of the film are also intercut with each other at points that, on the surface, seem disjointed and don’t immediately make sense. The “jarring” transitions, however, are one way that the film keeps all the sections of the film in sync with each other. The time periods should not be viewed as distant chronological zones, but instead as overlapping parallels, where the journey to conquer death remains the same across all time.

In the Popol Vuh, conquering death is accomplished Hunahpu and Xbalanque. They outmaneuver many traps and tricks set for them by the Xibalba lords of the Underworld, like how Tom attempts to outmaneuver death through the use of science. Hunahpu and Xbalanque are foretold, however, that they will die in a stone oven. When the lords of the Underworld try to trick the brothers into entering the oven, however, the brothers willing go into the oven of their own will. They are burned, and their bones are thrown in the river, yet they return with the power of regeneration. The acceptance of death has led them to peace and has shown them a new way to live. This is a lesson that Izzi has learned before the film even begins, and one that Tom fights against through his desire to conquer death.

Another device used in the film to draw distinct parallels between the different sections is Izzi’s manuscript. The story of Tomás comes directly from the book she’s writing, which immediately connects the Mayan Tree of Life as being an allegory for the cure for cancer. Izzi has written all but the final chapter, which she requests Tom to complete after she passes. Tom refuses, indicating that writing the final chapter would mean “closing the book” on Izzi.

Tom’s resistance to finishing the book and obsessing over finding a “cure for death” highlights his denial of its importance. Metaphysically speaking, it is a typical characteristic of human beings to deny this unalienable aspect of their relationship with nature. Izzi’s acceptance of her fate, however, gives us a psychological insight into her maturity as a person. Understanding that death will happen and learning to embrace it is the mark of maturity as portrayed in the film. This is what Tom’s arc has been leading to over the course of the entire film. He finally has this revelation as Space Tom, when he realizes that he doesn’t need the wedding ring he lost 500 years ago. Instead, what was important were the memories and time that he did have with Izzi. With this newfound outlook, he writes the thirteenth chapter, finally accepting his and Izzi’s own mortality.

The book ends with Tomás being allowed to drink the sap of the Tree of Life, but upon doing so, plants and flowers sprout from his body, returning him to the earth, but creating new life. This reflects the anecdote told to Tom by Izzi, showing that he has finally taken away the same lesson she had, and the same lesson learned by Hunahpu and Xbalanque: accepting the mortality you are given gives you the peace to live a more profound life.

The various iterations of Tom Creo battle with the universal fear of death, which persists across time, space, and culture, but he learns, through the stories and teachings of Mayan mythology, that when you stop trying to fight the natural process of death, you’re able to spend your time with the ones you love rather than spend it worrying about what will happen when they, or you, are gone.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.