Paranoid Thoughts in Relationships

How to Stop Overthinking After Betrayal

Struggling with trust after betrayal?

This article explores how past emotional wounds shape our thoughts, where paranoid thinking comes from, and how to gently shift the way we trust others — and ourselves again.

Key Takeaways

- Paranoid thoughts are often our brain's way of trying to protect us from past pain, not a sign of overreacting.

- Memory, bias, and emotional triggers are what our brain uses to connect patterns. It’s smart, but not always accurate.

- Interpretations are not facts — learn to pause and question what we’re assuming.

- Trust isn’t weakness. It's about believing in others, knowing the risks and knowing we can handle whatever happens.

- The way we think is a habit — Relearning our thinking pattern is possible. With self-awareness, gentleness, and repetition, we can create new thought patterns and feel peace again.

How Can It Be So Hard To Trust Again?

Being betrayed is harsh. It makes us regret, “Why didn’t I see that?” and forces us to learn a hard lesson: when something feels off, something might really be off.

But the deepest wound often isn’t the betrayal itself — it’s how hard it becomes to trust again. That struggle may feel like paranoia, and it’s painful.

You start noticing little things in your partner’s behaviors — slight differences in voice and facial expressions, earlier or later than usual work hours, notifications from friends you’ve never met, and so on.

You try to see the pattern in your partner’s behavior so that you can find suspicious inconsistency.

People say “you’re paranoid”, and “you think too much”.

You don’t need anyone else to tell you that — you already know.

But how can it be so hard not to think too much? While your mind understands, your heart still carries the wound. The more you try, the more struggle you feel. Like, trying not to think of a pink elephant never works — it only makes you think about it more.

And to be ironic, this anxiety can push your partner away.

But what if being paranoid can be a tool to make you a better person?

In this article, the word “paranoid” is not used as a technical or medical term but rather as metaphor — “jumping to conclusion” tendency that makes you feel suffocate, yet not clinically severe.

Paranoid thinking in this article is a learned pattern of thinking with no justified evidence, that makes you fear, worry and anxious about what might be happening. Being paranoid is a state of being controlled by fear, making you feel hopeless and powerless.

This article is inspired by a story about a woman, let’s call her Melissa, who’s struggling to trust her husband after being betrayed and getting divorced in her first marriage.

And I think she is not alone. Situation and the level of anxiety may differ, but many of us find ourselves struggling to shake off unjustified doubts at some point in life.

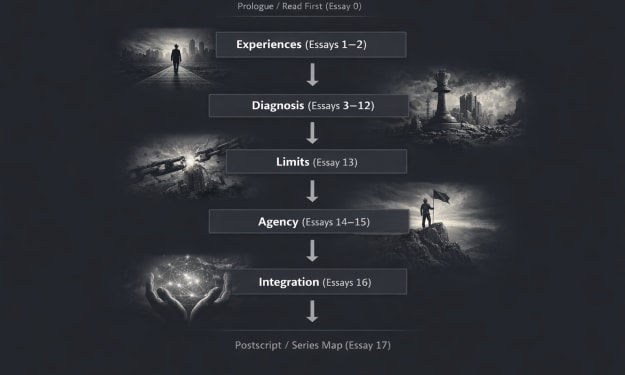

So what can we do to be free from it? I’ve broken it down into three steps:

- Understanding what’s happening in our brain

- Checking the components and reviewing the thought process

- Reshaping trust

Before moving on to the steps,

What is paranoid thinking?

Melissa lives with her husband, who works for a sales department. One day, he tells her that the company hired a new assistant for him. Melissa feels uneasy — her ex-husband left her for his assistant. Then, Melissa notices her husband leaving home earlier than usual for work.

And she thinks, “That’s unusual. Maybe he’s cheating on me”.

Do you think it’s extreme for Melissa to think that way?

You may be right - there’s absolutely no connection between “leaving earlier for work” and “cheating”.

But in her mind, the assumption feels so convincing. What’s filling the gap is her paranoid thinking. And when it happens, jumping to an irrational conclusion seems natural. And gradually, it becomes automatic.

She’s learned a lesson that inconsistency can mean unfaithfulness.

What’s learned can’t be unlearned. But it can be relearned.

Like, if you don’t want to think about a pink elephant, think about a blue elephant.

Step 1: Understanding What’s Happening in Our Brain?

Paranoid thinking is not just “thinking too much”. It's the defense mechanism of our brain.

Our brain is continuously anticipating what’s next. For example, you probably can read the phrase below.

Tnhak yuo for rieadng tihs aclrite. Plsaele laeve yuor cenommt bloew!

Research shows that our brain can fill the gap to create a coherent story.

On a flip side, our brain can see something that’s not actually there to make it plausible.

To form a coherent story, first, our brain observes, collects information, and notices a pattern.

Let’s say, Melissa’s husband leaves for work on Mondays with a rather unhappy face, because it’s Monday. So she notices a pattern — he’s unhappy on Monday morning. One day, she learns that a new assistant was hired.

Then Melissa notices he left for work earlier than usual, looking happier and more excited to go to work than usual Mondays. She thinks, “It’s unusual. Something is going on.”

Next, our brain keeps observing to connect information.

She notices that he’s wearing some different deodorant and checking his phone more often than usual. She also notices that her husband seems a bit distracted.

Finally, our brain makes assumptions based on the information gathered.

Leaving earlier + Happier Monday + New assistant + New deodorant + Phone Checking + Distracted

= He must be happy and excited to see his new assistant, wearing a new deodorant, checking his phone more often. His mind is already at work.

Maybe it can be stretched a little more. He must be having an affair with the assistant.

Does it sound logical? Maybe not. Does that sound somewhat familiar? Maybe.

What’s happening in our brain is “inductive reasoning”, where it uses specific observations to draw conclusions. Like we can read the jumbled letters, “Tnhak yuo for rieadng tihs aclrite”, we don’t need all the information to make an assumption.

To make a story, we use the observations collected and something else to fill the gap - our memory and common sense, or bias. Basically, our brain says, “I know this! I’ve seen it before! I know how it goes!”

Inevitably, its weakness is that the conclusions drawn are not guaranteed to be true.

And when we have past bitter experiences, the brain has another job to do - protecting us from experiencing the same pain.

It creates a mental alert system to detect a sign that caused pain before. It’s like our immune system - finding and attacking the known virus. It meant to protect us, but sometimes reacting too strongly and causing more harm than help, like an allergy.

An overworking alert system can override logic. It makes us fear over similar situations that hurt us before even when there is nothing logical to doubt this time. Like, the mere existence of a new assistant is enough to make Melissa feel uneasy.

Sometimes, we feel powerless. With all the “signs” that our alert system detects, we may decide not to confront the person because we know how they react. Or even when we do, we get what is anticipated.

“You’re paranoid. There is nothing to worry about”.

That leaves us one option - to trust.

And trust feels like giving away control, like there’s nothing we can do, making us feel weak.

What can we do to get out of it?

Step 2: Checking The Components and Reviewing The Thought Processes

Checking The Components

An assumption is made using the data collected. And if the data is unreliable, then the assumption made is questionable. So, we want to check the validity of the data.

For Melissa, are there any facts?

Her husband leaves with an unhappy face on Mondays.

- This may sound like a fact, yet it includes subjectivity because she “thinks” he seems unhappy. Someone else may interpret differently. So, this is an interpretation.

One Monday, her husband looked happy.

- Again, she “thinks” he looked happy. Maybe he is, maybe not. This is an interpretation.

The company hired a new assistant.

- This is a fact.

He started wearing a new deodorant.

- This is a fact. Unless mistaken.

He checks his phone more often.

- This can be either a fact or an interpretation. It will be confirmed as a fact if Melissa has been keeping a log of his phone use dated before the doubts. If she did, that’s kind of creepy and leaves us with different issues, so we don’t go there.

He seemed distracted.

- Someone else may not agree. This is an interpretation.

Now we have two facts, three interpretations, and one fact/interpretation.

An interpretation can be tricky because they often look like a fact.

This is where people who are sensitive to changes need to be extra cautious because their level of noticing small changes in their surroundings can be unbelievably high. They can recognize tiny details of the voice or facial expressions. And they’re experts at spotting inconsistencies, which may look suspicious enough to make a rather biased interpretation.

When checking the components, we stay objective. And when we find something, consider asking,

“Is it a fact? Or, am I slightly bending what I see and interpreting to back up my doubt?”

We can also casually check the person without sounding like an accusation.

“You’re checking your phone again. Is everything okay at work?”

The answer, or non-answer, may or may not confirm the component. We may feel relieved that the phone use is purely for emergencies at work, or not. The goal is to be objective and also to give the person a chance to explain.

If lucky, the answer can help us clear the doubts. And the more we realize that our interpretations can be biased and incorrect, the easier it gets to objectively see the situation without choosing irrational interpretations.

Reviewing The Thought Processes

During the process of making assumptions, we use the components, either facts or interpretations, but they’re not enough — we still need to fill the gaps. This gap filling process plays a big role in a paranoid thinking pattern.

Let’s review what we have.

Leaving earlier + Happier Monday + New assistant + New deodorant + Phone Checking + Distracted

= He must be cheating with his assistant.

Which component does she use the most? Does she use her interpretations more, or rather focusing on facts?

Or let’s be honest. Does it even matter whether we have facts or interpretations?

“He looks suspicious, so he must be guilty”, right?

What thought process did Melissa go through to draw a conclusion?

“Okay, it's Monday. So my husband must wake up a bit grumpy, skipping breakfast, and leave the house without proper goodbye. Wait, he said “good morning”, and had coffee? That’s unusual. Wait, isn’t his new assistant starting today? He’s checking phone again and wearing a new deodorant. He seemed happy but a bit distracted as if his mind was already somewhere else.

This feels familiar. My ex husband cheated on me with his assistant! It’s the same! Oh my god! My husband is cheating on me!”

Traumatic experiences of her ex-husband, combined with the trigger of “assistant” made her jump to the conclusion. And the “trigger” is powerful enough to make us ignore rationality, possibly bending the facts to see what needs to be seen.

Casual confirmation used for interpretations may not want to be applied here. “You have a new assistant! Are you cheating on me?” can be a huge accusation, especially for innocent people.

And even when we ask and our doubts are cleared, the peace of mind will be temporary. Even worse, it makes us become addicted to the confirmations. The more we seek, the more we crave.

We notice small inconsistencies and we have to ask, “are you cheating?” We may feel relieved for a little while until we find other inconsistencies that surface our triggers. Seeking confirmation gives temporary relief — but also creates a dependence on reassurance.

So how can we change our undesirable thinking patterns from inside, instead of depending on others?

Acknowledge our brain is doing a great job

It’s trying to protect us from being hurt. We don’t deny its intention, certainly don’t doubt its ability to see things. But it’s been overreacting, and THAT is hurting not helping.

Instead of being dramatic, it can do its job by calmly observing. When it notices something, there’s no need to ignore the information. Just don’t panic and take a mental note, so we can act on it when necessary.

Like, “I noticed some inconsistencies. I’ll keep an eye on this just in case”, instead of, “I’ve seen it before! He must be cheating!”

Be careful with all-or-nothing thinking

Instant reaction can be “he must be cheating!”, as if the alternative is “he is an angel”. No, he is just a human, who can notice the beauty in people other than his wife. We can use the “probability scale”, not “Yes/No” thinking.

Instead of, “He is cheating or He is NOT cheating”, we can pause to think:

“On a scale of 1-10, how likely is he cheating based on the information gathered?”

This can allow us to pause, be objective, and stay open to possibilities, giving us options of ideas, instead of jumping to conclusions too soon with a tunnel vision.

Don’t give suspicion a power to dominate our minds

People can lie. People can be manipulative. But we don’t assume the person in front of us is lying and manipulating without enough evidence. We want to be in control and not jumping to worst-case scenarios without solid proof.

Sure, we want to be smart and cautious, trying not to make the same mistakes, but we don’t want our suspicion to cause us stress or interfere with our relationships. So, when suspicion starts taking control of our mind, let’s pause and calmly and objectively see what we have.

If the control is unlawful, we gently tell it to step back and hold.

Acknowledge that it’s more about the past, not present

At this point, we already know what we’re actually dealing with — our past. The memory of being betrayed after trusting a person makes us doubt our ability.

“Am I good enough to notice things without missing something suspicious?”

“Am I good enough to make an accurate assumption based on the information gathered?”

“Am I good enough to detect and avoid people who can hurt me?”

We are essentially doubting ourselves.

Because last time, we failed. We doubt whether our ability to trust is reliable.

What does trust mean anyway?

Step 3: Reshaping Trust

Paranoid thinking can be deeply connected to how we trust others. An unhealthy way of trust can make paranoid thinking inevitable. So, understanding and dealing with it can help us change the way we think.

Trust can either represent weakness or strength.

When trust represents weakness, it can be nothing more than an empty promise or hope. We give away control over the future, trust, and hope for the best, as if trusting is the only way. Or trust can instantly be connected to the images of past betrayal. Trust can make us powerless, hopeless and weak.

Trust can also represent strength when we understand the nature of it.

Trust is not a guarantee

Nothing can stay the same forever, including your partner, surroundings, and yourself. We can never know what happens, and that’s just the way it is. Like any other things, there is no guarantee that trust will be kept.

Even without all the “traps”, your partner can still fall, and so do you. There is always a certain risk to trust someone. It’s about weighing the disadvantages and advantages of trusting the person.

Do you want to half-trust with constant anticipation of being hurt? Or do you want to choose to trust fully — not because it provides you safety, but because you are strong enough to handle whatever happens?

Trust is more about us than others

Trust is not about blindly believing in others that they will never hurt us. Trust means we choose to believe in people despite the risk of getting hurt, knowing we can handle the outcomes.

It means believing in ourselves that we will heal no matter what happens. Trust means taking control, without letting fear dominate our mind.

We’ve checked components, reviewed thought processes, and reshaped our trust. We need one last push — accept the fear and decide we try to change.

Accept fear without letting it control actions

We fear, and it’s natural. Instead of pushing away or pretending that it’s not there, accept the fear but choose not to act on it. Like, “I don’t like that he has a new assistant. It reminds me of my ex-husband. Sure I feel anxious, and that’s understandable. But I’m not letting my fear control my mind nor define our relationship.”

Paranoid thinking is just a habit

I know it feels impossible not to jump to conclusions — that’s why it’s called “triggers”, instant reactions that feel inevitable. But the way we think is also our habits. It may take more time to adjust compared to physical habits, such as walking 5 minutes, exercise at gym, eating veggies, etc., but certainly, the way we think can be changed.

And firmly believing “I can’t change” can never help.

The key is to accept whatever the feelings we have, let them be there, and gently choose not to act on them. Sure, it may require discipline at first, but the more we choose the path we want, the easier it gets to go through the same path the next time.

Like when we draw a line on sand to flow water, water may not exactly follow the path at first. But when we repeat tracing the same line over and over again, the water can never leave the path.

We can relearn the pattern.

Wounds Can Make Us a Better Person

Relearning the pattern and getting over the past can not only make us stronger, but also make us a better person. We can understand others' pain because we have experienced one.

Once healed, the wounds we carry can bring more empathy towards others. And with empathy, we can make our surroundings more comfortable.

When friends are facing challenges, we can listen with more empathy than those who’ve never felt the same kind of pain.

And the ability to notice small details and fill the gaps with our imagination can be a gift, when used correctly. It not only helps us stay away from potential dangers, but also be used as a tool to help others.

If we work as a barista, we can notice our regular customers seem a bit upset. Because we notice, we can gently ask how they’re doing, making them feel better.

If people look offended after we say something, we can immediately notice the changes in their facial expressions so that we can ask and correct any misunderstandings before it’s too late.

If our friends, family members or coworkers seem depressed, we can be the first, or the only ones who notice something is not right. And we can do something to make things better for them. The list is endless.

And as we’ve learned to be open to multiple possibilities, we know how to see things without bias.

Even when we encounter someone who looks grumpy, mumbles, and cuts into the line, we can look at the person with a rather calm, objective, and possibly a gentle way.

“He can be depressed living alone and acting out is his way of expressing loneliness.”

Maybe correct, maybe not, but that’s not the point.

We choose not to let something uncontrollable affect our peace of mind.

We can use our power to make us a better person.

Final Thoughts

Struggling to trust again after being hurt is not a sign of weakness. It only means we’re human.

Our minds are designed to protect us, even if that means overreacting sometimes.

We don't need to silence our thoughts. We just need to understand them, guide them, and remind ourselves that trust can be a choice rooted in strength, not fear.

We’re allowed to be cautious and compassionate — with others, and with ourselves.

Thank you :)

About the Creator

May Rashi

Stories, thoughts, and reflections — rooted in curiosity, shared with intention.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.