Neither Here Nor There

arrival, departure, moments in between

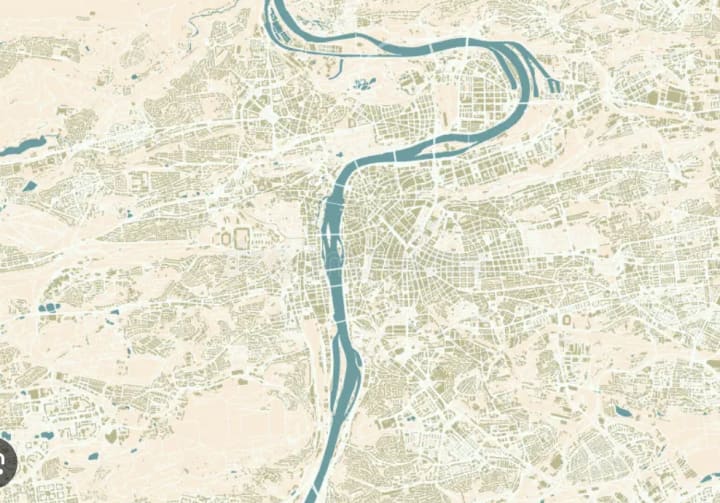

On most maps of Prague, the Vltava River appears to cut the city straight down its middle, save for one bend that may, to some, resemble a lazily drawn P. The Czechs have always possessed a good sense of humor and an acceptance of their fate—I like to think the ancient gods etched the letter in the earth to give the city’s founders a hint. Praha.

When I first arrived on the banks of the Vltava, I had never read Kafka, listened to Dvorak’s symphonies or admired a Mucha painting. Deciding to study abroad took the research and forethought of a Google Image search. I took one look at St. Vitus Cathedral bearing down over the Charles Bridge and packed my bags. I wanted beauty and the unknown; I got both. I was nineteen. When people asked me where I was going, I was helpful on only the most basic of details. Actually, it’s the Czech Republic now. And yes, they speak Czech, or so I’ve been told.

Nearly a decade later, on my last weekend in this city that I’ve come to call home, I ride the number 17 tram, a line that traces the edge of the river, disappearing briefly into the land on the northern half of the city before spitting back out on the other side of the bank. I've sat with my forehead against its windows countless times, taken in the same view of the water in all seasons as it passes the stops that have been etched into me over and over. It is my favorite way to travel, this transitory space protected from the world but in it at the same time. Always in motion, neither here nor there.

I watch a young mother board the streetcar holding a woven basket of freshly picked yellow cherries in one hand and a leash attached to a massive German Shepherd in the other. Three little blonde-haired boys under the age of five trail behind her, all wearing identical blue windbreakers. (It is late May and warm, but because they are Czech, they must dress for the worst at all times; winter is ever lurking and dangerous). The first real pang of sadness hits me. I don’t know when I’ll take this ride again. I don’t want to forget these little scenes of family life, the 21st century mullets and the smell of smoke and beer and the automated announcements of Dveře se zavírají. The doors are closing.

I don’t want to get off yet, so I let the 17 take me back and forth.

Výtoň, arrival. By September 1st, autumn has already settled in comfortably and put its feet up. Commuting in the freezing mornings feels like a total affront, transferring tram lines at 7:30 in the morning a stark contrast to the sheltered life of a small Connecticut campus. The city gives its unwavering permission, however, to revel in that misery with all its gothic doom and gloom. The terror of being shuffled between occupying powers for three centuries, first by the Habsburg Empire, then Nazi Germany and finally the USSR, lingers in the streets with the memory of various self-immolations and defenestrations. The past has imprinted on the Czechs, this much is clear on the surface—the lack of smiling or acknowledgement of the other in public, their frequent indifference to your woes—these things tend to baffle Westerners.

The first morning of our mandatory Czech class, I decide to forgo the tram and walk instead. I get lost in the narrow, cobblestoned streets that seem to do nothing but twist and turn, arriving ten minutes late. As I stand in the classroom entrance breathing hard with twenty pairs of eyes craned around to regard the disturbance, I realize that I have come to a country in which I don’t know how to say hello. The professor, a stout woman named Agáta with hair dyed a striking shade of copper, who I’m about to learn takes no prisoners, says nothing. Instead, she turns to the blackboard, picks up a piece of chalk, and writes: Já se omlouvám, že přijdu pozdě. Facing me again, she points at the sentence, indicating for me to read aloud. I take a wild stab at the sounds I don’t yet know how to pronounce. I apologize for arriving late.

From then on, I opt to take the tram with the others, descending together at Výtoň before beginning the perilous climb up to Vyšehrad, the 13th century fort that contains the converted church where we spend our weekdays. We trudge up the steep hill, which curves gently for an eternity before finally delivering us across the threshold of the Medieval barracks. Always dark, cold, certain corners smelling of smoke and urine, the study center forces me to huddle at my desk, never removing my coat and scarf, over a two-ounce cup of vending machine cappuccino. I learn to swap American comfort for the charm of history. This is the height of civilization to me.

Agáta has us practice how to order coffee correctly (When asking for káva, one must use the accusative case and decline to kávu. If you forget this rule, the barista will pretend to not understand what exactly it is that you’re after). David, who we have kindly nicknamed Mr. Blabla, chews tobacco while rhapsodizing on Kabbalic traditions in Judaism, his yellow spittle cutting through the clouds of decades-old chalk dust before making contact with the front row. Anna, an American like us, interrogates us about the feminine perspective on violence in cinema. Rumored to be having a longtime affair with one of the country’s most lauded film directors, she’s sticking around to raise their lovechild, who sits quietly in the corner of the classroom and does his schoolwork. Bohumil, the transatlantic history teacher, mumbles into his beard continuously for an hour, looking up and pausing only to ask softball questions like, “What does it mean to be American?” and “Will God ever forgive us?” Breaking from my identity as a good student, I stare at him in silence.

When class is over I stumble my way back down the hill and climb onto the first tram that pulls up. The sun is starting to set over the Vltava, the first of many times I will be blinded by the light coming off the water through the streetcar windows. An elderly woman with a cane sits down opposite me and smiles gently with her mouth and with her eyes. She understands me, sees me taking in this particular and new beauty. Framed from behind by a halo of incoming rays, she holds my gaze and I do my best to telepathically thank her for being my guardian angel. Děkuju, děkuju, děkuju. I get off the tram in the Old Town on a whim, not particularly close to my flat, stumbling around still unbalanced by all the light reflecting off the pink and yellow facades. The sound of violin is in the streets or in my head; I follow it around the city and realize that I am really here.

Veletržní palác, descent. The tram stops directly in front of the National Gallery, a gargantuan functionalist structure named for the trade grounds it hosted prior to the art collection. This is the only place The Dreamer and I make an appearance in public together during the daytime. Normally, if we are together, it is night, and we are holed up in his strange flat on the edge of the city. His room is all wood and navy blue—always a furnace, which I love in the Prague winter. It feels like we are tucked away in the mountains somewhere. In the dark I can still make out his dark beard and long eyelashes, his many tattoos. It is in these blue sheets of his that he tells me he just won’t be able to stay put.

“I want to see everything,” he whispers.

“You can’t see everything.”

My answer is cruel; I am stating the obvious and speaking to him like a child, although he is thirty-one to my twenty-three, and I am done for. I understand his pain, because I remember being a small child in the school library and realizing I would never be able to read all the books on the shelves surrounding me, much less all the books that had ever been written. It just wasn’t possible.

“I have to try.”

I bite my tongue, knowing there are no words to argue with him, that he’ll be off to see the whole world again in a few months. This was always the plan, after all, to spend a year in Prague teaching English before moving on. My only hope is that I can make him see this place as I do. I’m confident that enlisting the nation’s best artists will convince him there is enough beauty to stick around. So we spend an extraordinarily grey and cold winter’s Saturday, even by Prague standards, slowly contemplating the five floors of displayed work at the gallery, which gives us an excuse to not speak.

We discover Petr Nikl’s Vyhnání (The Expulsion), a postmodern take on Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden. In the Czech version, the colorful background and angel have disappeared; Eden appears as nothing but the vague suggestion of an archway. Adam's and Eve’s bodies are stuck with textured yellow stigmas, as if they walked through a field of burrs on their exit from Paradise. Their demise is so evident, the feeling of being punctured so tangible.

On the way out, we pause on the staircase in the lobby to stretch for a few minutes. We don’t speak, though there is no more art to ponder in thoughtful silence. We walk back out into the cold as the sun begins to set and board the tram. He still wants to walk out of Paradise; I do not.

I later learn that Nikl belonged to a contingency of artists nicknamed "The Stubborn Ones."

Palackého náměstí, delay. After The Dreamer leaves, I sleep on a mattress on the living room floor of a four-story walkup. My window faces the busy Palackého náměstí, a square which sits right on the river’s busiest crossroads. Trams roll from north to south and east to west at all hours of the day and night. Looking down upon the whole scene is a collection of massive Art Nouveau statues dedicated to František Palacký, the square’s namesake and father of the Czech National Revival, the movement that saved the Czech language from extinction during the Austro-Hungarian occupation of the 19th century. I often find myself staring up into their grotesque faces, metal weathered to turquoise by the elements over time.

I still dream about The Dreamer even though I say I won’t allow it anymore. I will bully my subconscious into submission, forbid the strange, slow nightmares that tell me something I have no desire to understand.

Every day I set out through the square and pick a direction, any direction. I am stubborn, determined to stick, and choose my own quiet Czech revival. Every night I lie on the floor and let the trams shake me back into this city.

Staroměstská, layover. I leave work by 4pm at the height of the pandemic and take the tram to Staroměstská, located next to the river on the edge of the most tourist-laden area of the Old Town. The sky is almost completely dark by the time I exit the tram and every facade twinkles with Christmas lights; the air is smoky with the smell of mulling spices and meats roasting on open spits. I take my time tracing the same path I’ve become accustomed to: I walk through the giant arch that leads to the Charles Bridge, skirting around the crowds. At some point I stop for a mulled wine and sip it as I walk.

This can't be correct. The spikes of 10,000-15,000 cases per day provoke every type of closure and confinement. Christmas markets are closed and there are no tourists. But my mind does not let me remember it as such, and I prefer to keep it that way. My love affair will not be interrupted.

Dvorce, waiting room. The sauna lies directly between the Dvorce tram stop and the river. I don't know who started it, whose idea it was, but my girlfriends, fellow expats, and I begin to frequent the spot, shedding our clothes and whatever prudish sensibility we arrived on the continent with. We stare at each other, beet red, daring someone to cave first. When someone just can't take it anymore, we scuttle from the sauna to the cold plunge and submit ourselves to another form of torturous delight. I don't think it is possible to be happier than this.

Looking out over the hills and bare faces of rock across the river in the dreary afternoon light, I think for a moment I could stay forever. I could do this. Come here to sweat every week, take the tram to work forever, walk around the Old Town when there’s nothing else to do, drink mulled wine in the winter. Wouldn’t that be okay? Commit to learning how to speak Czech fluently, meet someone, spend weekends in the countryside. Despite my protests, a vague sense of needing to move on again sits patiently on my right shoulder.

Výtoň, departure. I want time in this place back, to not lose this sweetness, to slow down so much I go back for just a moment. To relive every moment of heartbreak in my city of love, where I was the most together and the most alone. I walk from one end of Prague to the other, stepping with more force than necessary. My feet hurt; even as blisters form, I refuse the tram and keep marching, part of me hoping bloody stubs will form and keep me from the inevitable.

Time refuses my supplication. I am back at Výtoň, at the end, back at the beginning, and there is nowhere else to go.

Dveře se zavírají. The doors are closing.

Comments (3)

Wooohooooo congratulations on your win! 🎉💖🎊🎉💖🎊

Congrats on your win!

It's a love letter to Prague and it's great. I wish travel guides were written with this level of adoration and color. You really bring the scenes to life and I want to go visit! Clever take on a Challenge!