British aesthetician Clive Bell once stated: “Everyone in his heart believes that there is a real distinction between works of art and all other objects.” French conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp challenges this statement with the “ready-made” found objects such as the Fountain and the Bicycle Wheel. “Duchamp believed that any ordinary object could be elevated to the status of an artwork just by an artist choosing that object.”

Duchamp’s goal was to "put art back in the service of the mind." In other words, the artwork is not the actual object but the idea behind it (or rather the mind of the artist). This idea is reinforced by Duchamp's short film with the spiraling lines and words. Included in the caption for this film was the idea that art should create a "field where language, thought and vision act on one another" (Jasper Johns). Art that moves us or causes us to think is a powerful way to express ideas. Duchamp broke the rules in terms of artistic expression. If we compare the artistic work of ceramic artists, specifically creating utilitarian objects like vases, bowls, pots, etc. to Duchamp's “readymade” objects, we can say that Duchamp broke the rules pertaining to utilitarian ceramic artwork. He took objects that are used and made them into objects that no longer served a purpose. This is explicitly seen in Duchamp's Bicycle Wheel. Neither the stool nor the bicycle wheel can be used.

The other rule Duchamp broke was the aesthetic expectations of fine art as depicted by classical artists of the Renaissance, Romantics, and Classical Antiquity. The message of his work is neither political nor religious in nature as was the case with many artists of the ancient past. Man is not at the center of his work. Duchamp isn’t the only artist during this period who challenges the status quo of artwork. Moving from representational art to conceptual art.

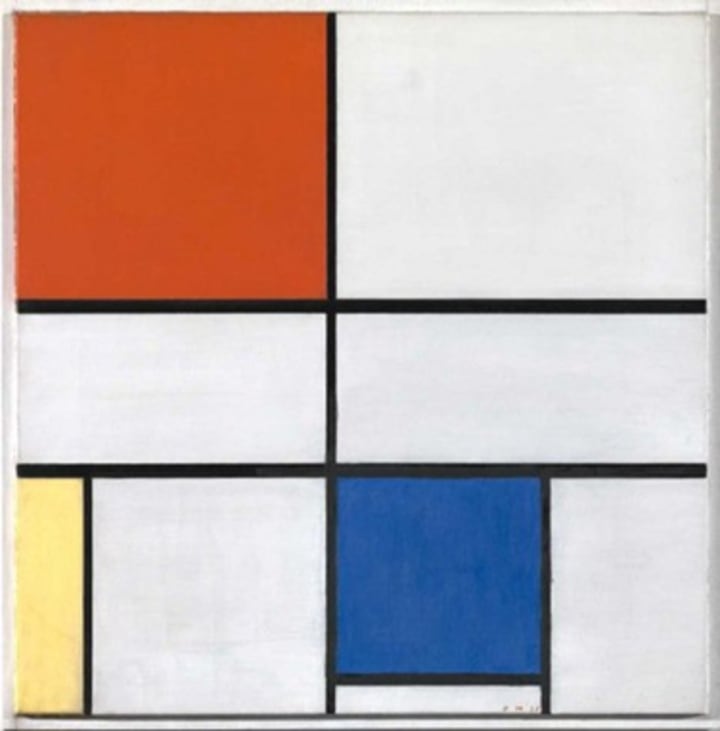

Piet Mondrian's work, like Duchamp's, changes drastically from his Tree series to his more well-known Neoplasticism paintings. Piet Mondrian's work reminds me a little of the larger swatches of paint that Mark Rothko employed. Mondrian's development of Neoplasticism became one of the key documents of abstract art. In the movement, he detailed his vision of artistic expression in which "plasticism" referred to the action of forms and colors on the surface of the canvas as a new method for representing modern reality.

Where Rothko was attempting to move the observer, Mondrian was simplifying forms through the use of straight lines and blocks of color (primary colors). Mondrian is best known for his abstract paintings made from squares and rectangles. However, he started off painting trees. While examining the visual aspects of his abstract paintings we might still be able to see the tree for the forest of lines and squares.

Lines and squares evolve in the landscape of architecture through key figures such as Frank Lloyd Wright, who wanted to blend structure with nature.

“Wright believed in creating environments that were both functional and humane, focused not only on a building's appearance but how it would connect with and enrich the lives of those inside it. Moreover, at its core, his organic design philosophy states that architecture holds a relationship with its time and place.”

We see this in his most famous structure Fallingwater located in southwest Pennsylvania and is considered the crowning achievement in organic architecture.

“The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935), by Walter Benjamin, is an essay of cultural criticism which proposes and explains that mechanical reproduction devalues the aura (uniqueness) of an object d'art. In essence, the aura is the "one-timeness" of the experience, the situation in which the subject meets the object that cannot be reproduced. Historically, works of art had an 'aura' – an appearance of magical or supernatural force arising from their uniqueness (similar to mana). The aura includes a sensory experience of distance between the reader and the work of art. The aura has disappeared in the modern age because art has become reproducible.

When we take a look at Andy Warhol's work we see this reproduction. Andy Warhol was a man who created pieces that blurred the line between commercial and fine art. His industrial method and desire for mass-production took the personality of the artist away from the work, leaving him disconnected from his art. In his 1960s studio – known as the Factory – he employed studio assistants to make his work for him. Warhol realized that he could increase the commercial productivity of his art more quickly by getting others involved in making it. The Pop Art of the 1960s, like Impressionism, is often criticized for its technique and is it really art if it is mass-produced or if the work is done by assistants, rather than by the "artist" who conceived the idea.

Bibliography

Bell, C. (1914). Art. London: Chatto & Windus

“The Philosophy behind Iconic Frank Lloyd Wright Architecture.” Engel & Völkers, https://www.engelvoelkers.com/en/blog/luxury-living/architecture/the-philosophy-behind-iconic-frank-lloyd-wright-architecture/.

Winner, Ellen. How Art Works: A Psychological Exploration. Oxford University Press, 2018.

About the Creator

Rebecca A Hyde Gonzales

I love to write. I have a deep love for words and language; a budding philologist (a late bloomer according to my father). I have been fascinated with the construction of sentences and how meaning is derived from the order of words.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.