In defense of ontological naturalism

Atheism from ontological naturalism

People arrive at atheism from different directions and different starting places, taking different paths, for different reasons. For some atheists, atheism is understood to be a conclusion about how the universe operates. More specifically, atheism can be one component of the more general conclusion that the universe operates within the constraints of ontological naturalism. That is my perspective.

Staying within the bounds of matching our beliefs regarding how the universe operates to the available empirical evidence is not only a sin qua non of science, it is more generally a sin qua non of being rational. This is equally true for theists, agnostics, and atheists. Everyone who engages in arguing that their theism, agnosticism, or atheism is the best fit conclusion with the overall available evidence about how the universe operates is thereby attempting to make a rational argument. That is, in and of itself, good. Not everyone consistently engages in this rational form of debate over this dispute, or other such disagreements, which is unfortunate.

A theist may argue that from nothing and randomness the only possible outcome is nothing. An agnostic may argue that a scientific mindset favors skepticism over certainty so both theism and atheism are equally overstepping. As an ontological naturalist (a.k.a. atheist) I do not find such arguments for theism and agnosticism compelling. My burden is to try to explain why.

What about the role of falsifiability in science? Maybe as ruler of heaven Zeus led the gods to victory against the Giants (offspring of Gaea and Tartarus) and successfully crushed several revolts against him by his fellow gods. Why do we reject that possibility when we cannot falsify it? We reject such far-fetched claims, not because they have been falsified, but because we recognize that they are inconsistent with what we know about how the universe operates, which is functionally equivalent to having been falsified. Also, we recognize that such claims, with very high probability, have non-empirical based origins. There is no certainty here, we cannot go back in time and witness the origin of these stories, but we do not need such certainty to dismiss non-evidenced declarations that conflict with our evidence based understanding of how the universe operates. That last clause about the conflict is centrally relevant here, it is the clause that agnostics mistakenly tend to omit from proper consideration when they criticize atheism for supposedly overstepping by concluding too much from too little.

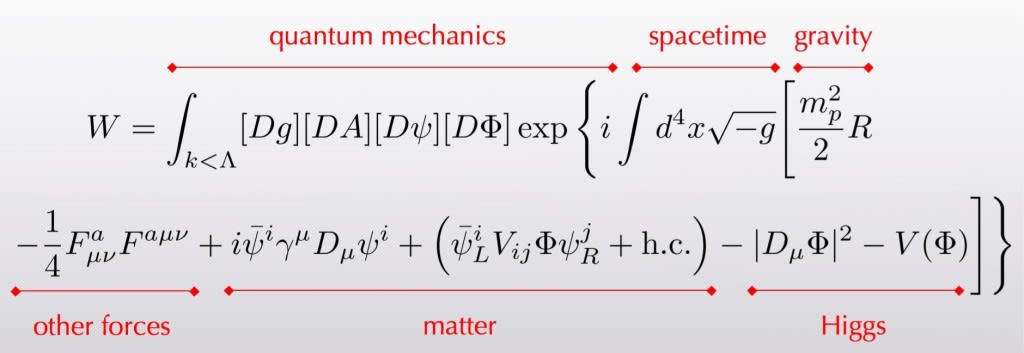

Science relies on natural methods and reaches natural conclusions because that is the only combination that has a track record of being succesful. Science is a pragmatic search for understanding how the universe operates. The claim that science a-priori rules out supernatural methods and conclusions, as the critics of atheism sometimes claim, is mistaken. Any method and any conclusion that works will, by virtue of its success, come to define science. The methods and conclusions of science are themselves a product of how the universe operates. From this perspective modern science itself functions as powerful evidence for ontological naturalism, maybe even more so than many scientists appear to recognize, or are willing to publicly acknowledge. The federal government contributes significantly to funding science. One Senator who insists the funding not go to any endevors that indirectly supports atheism is enough to silence scientists dependent on such funding.

Physicist Sean Carroll has explained this thusly: “if the best explanation scientists could come up with for some set of observations necessarily involved a lawless supernatural component, that’s what they would do. There would inevitably be some latter-day curmudgeonly Einstein figure who refused to believe that God ignored the rules of his own game of dice, but the debate would hinge on what provided the best explanation, not a priori claims about what is and is not science.”

Atheism is consistent with practicing epistemic humility. We are aware of the limits of what we can know. We are also acutely aware of the tendency of people to mistakenly claim to know more than what they actually know. It is precisely because of this awareness that we are so dismissive of mere declarations of an unconstrained supernaturalism as being factual, particularly when it manifests itself as a deity to be worshipped or prayed to. An honest evaluation of the empirical evidence verified understandings of how the universe operates that we have, which is more relevant than what we do not know, consistently favors ontological naturalism.

If the overall direction of the available relevant empirical evidence changes as we continue to find more evidence, our beliefs should change accordingly. We cannot know how our best fit conclusions will change hundreds of years in the future. Generally we build on what we know over time as we learn more. Revisions that instead fundamentally overturn and reverse our understanding of how the universe operates occur much less frequently. Accordingly, it is not necessarily more rational to refuse to reach a definitive conclusion due to the presence of unknowns and uncertainty. At some point we have enough evidence to favor one conclusion over others, and when we reach that point, we are justified in favoring that particular conclusion. By doing this we have not closed the door on changing our beliefs if the overall direction of the available evidence changes when we learn something new.

Absolute certainty and absolute knowledge are beyond our reach. Of course, the available empirical evidence could be misleading, it could be forever unobtainable yet centrally relevant, supernaturalism could somehow be true, Zeus could somehow be real, etc., in which case we will be forever wrong and deceived through no fault of our own. To base our conclusions on such a possibility, given how successful following a best fit with available evidence paradigm has been, is to give extreme skepticism, and fear over being mistaken, a veto over common sense.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.