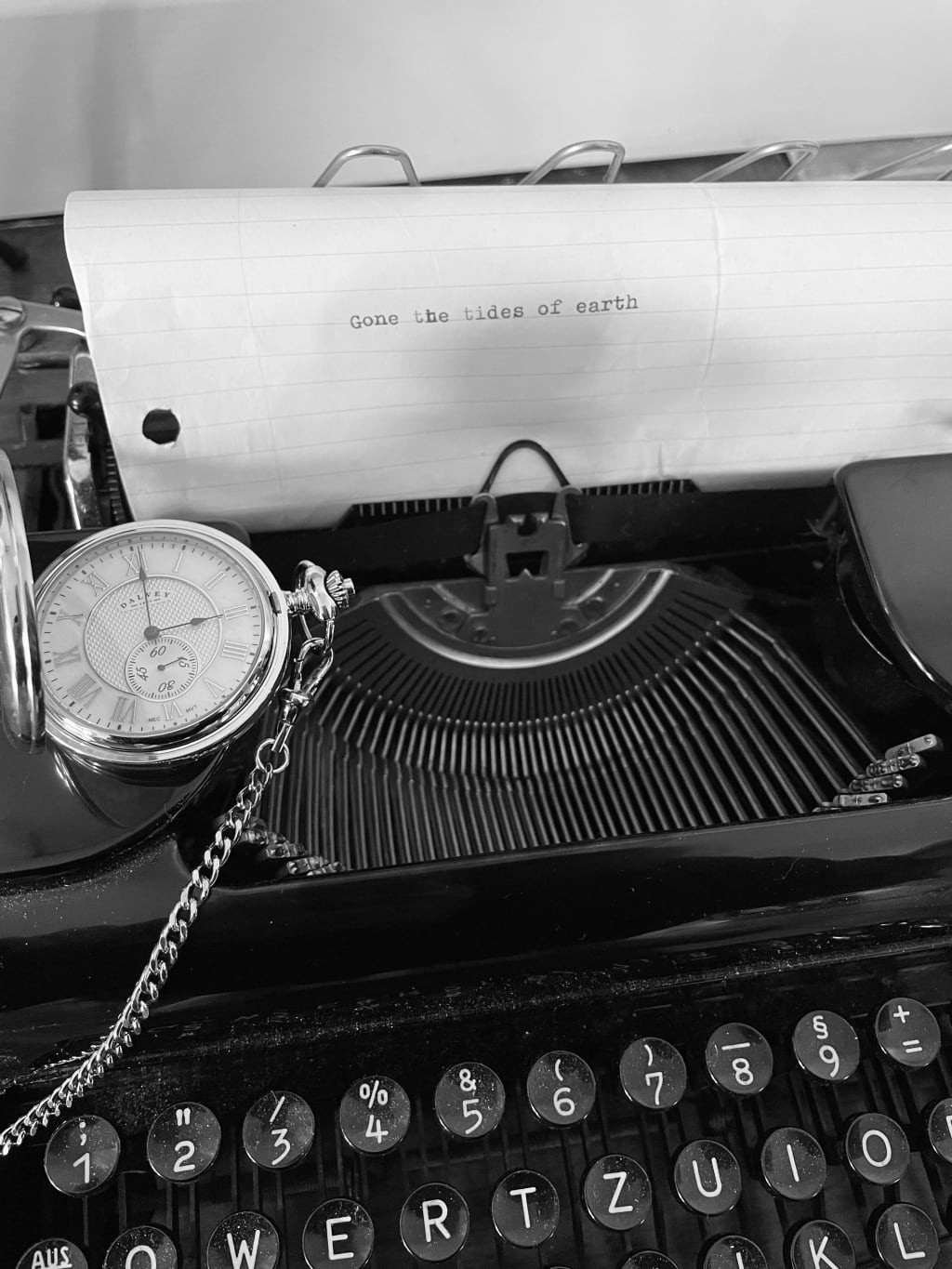

Gone The Tides Of Earth: A Novel

Chapter 3

Driven by the feeling, I press ahead to a jagged threshold spliced in corner of the most distant wall; an uneven, roughhewn opening like a natural cavemouth. Dark matter flakes swirl in shrouded specks, iodized in the stale air. A chilly draft flooded out, flew beyond blackness of what lay within, dank frigidness seeping into bone. Pallid gunmetal-blue glints off the edges of cavernous rock - mirage perhaps - as I step forth, down slab steps unto what awaits below. Inside as expected she is, and prostrated aground, readying preparations with resources possessed herein. An old lady, garbed in a luxuriously coloured robe of hempen twill, feet covered with vinyl sandals; hair incredibly long, running down back in set tangled knots, of beautiful thickness and sandal-brown colour.

The room is decrepit, bare, plain by terms of materials though rich with culture. There are frescoes on the walls centuries older than those painted in the chamber or corridor. Half the floor is laid with wood but stripped; they are planks of sanded driftwood which had long ago begun to rot, that at some point turned to tendrils of entwined sinews, snaking along the floor like tan crusted leather.

Going steady into the damp cellar, I proceed modestly in the manner a cardinal might progress towards conclave. The rest of the floor is grey granite, old as cold to the touch, chalky, faded and tinged with a sickly hue. Some musk reeked the worst, pervasive to a degree that a gaseous air of the cellar hung thicker, muggier than that without. Treading over damp, rot floorboards I crossed the room, headed for where she kneeled on granite. They were like walking atop heavily matted grass, or tall stalks of yellow grass when the wind has pinned them down. Slivers of dull, reoccurring light agleam caught my peripheral vision at several intervals, bluish muted moonlight from misshapen triangular windows carven out stone, in the backwall high up above any blistering frescoes.

A body-length from where she toils, I pause as she glances up, in a way that plainly tells me to halt. Not speaking, she returns her focus to the task at hand, eyes fierce and countenance haggard, skin of face and hands deeply wrinkled from a life lived under the sun.

‘Can I be of service?’ I ask.

Without looking up, she raises two encrusted blue fingers that told me to wait patiently a little longer. In an arch around the field of labour are a dispersion of unique objects for a rite. Nearest to her is a firepit, carved into stone floor and recently set, harbouring a small fire spitting ash and ember, kindling and bundles of cords stacked aside. The edges of the pit were coated with layers of char, crisped from centuries of usage. All else, arrayed around her: various tools for the ritual we purposed.

A set of basalt mortar-and-pestle she had used to grind a cobalt, sulfuric residue into a sticky paste. There were sticks of incense, sage, several already burning from a round ash catcher; a small brass cauldron filled half full of water next to a frying pan peppered with garlic, onion, parsley, lathered with goat butter; two ceramic plates. Close to the far side of the room, nestled below the isosceles windows was the climactic object: a wide, hefty bronze basin filled to the brim with seawater. Of all devices thereof it was the most beautiful, deftly crafted with fine metals, painted with finer artistry; scenes of the rising sun and of people in great fields, under mountains and monoliths and in temples at worship, of baptism in the sea glimmered below its rim in elaborate detail and colours, much older than the frescoes.

Soon she peered up, looked at me in a swift motion - an immediate snap of the neck, gaze finding, instantly fell - and eyes calculating like a hunter honing unto prey, sharp with almost feral severity.

Vague moonlight twinkled through the miniscule polygons, flickered over the room and its contents. Traces of gilded illustrations on the basin glinted with an ichorous tinge as moonlight washed upon it; glittering gold as if the finger of Zeus scrawled out an auspicious portent before our vision. The light shifted and lit her profile where she stared from the floor; eyes menacing yet thoughtful, resolute, bearing weight of the darkness upon vessel of a good spirit who has lived long, endured many things, seen far too much else; green with little flakes of yellow etched around the iris. The wrinkled face had flesh taut like combed leather braided and held back with a clip, pigment smooth brown, tanned; already the blue crust was painted in fine swirls, lines, spirals, crescents, drawn upon both cheeks, temples, and in a rainbow over the brow: there was a large, crude circle with projected lines, thrice miniscule polygons of the same, another of broad lines collapsing atop each other against wavy curls designed as if swelling up, last a lonely cratered orb with its inside coloured in: the sun, starbursts, tides of the sea and moon; face that is diagram of Earth and celestial heavens.

From the floor her gaze hung onto me like that of the Fates, she rose and started forward with the mortar. The way she stood, like a bird erecting on the strength of thin hind legs was quite nimble for her age. She moved briskly and determined, coming forth fervid, of an ardour channeling the intensity of a narcotics-intoxicated shaman. An armlength from where I stood, she ceased, being closer I could tell there was nothing to fear in the tenacity of her step. Two fingers went into the mortar, scooped the paste like a fine gel and she ran them over my brow, right to left in a smooth line; gaze worked voraciously over her work as though drinking in through the eyes. The paste was dense, cold and felt tight as it dried into a crust upon contact; she scraped more, pressed into cheek, drawing fingers down vertically. Next made marks on temples then neck in circles, lines and crosses.

Rapt I heard fingertips scrape the bottom of mortar like scratching rock, focused intensity remaining unchanged. She withdrew her fingers, placed them to my other cheek, making several dots which she filed into multi-sided points via fingernails. Lastly dragged a crescent around the dots, faded it downwards along my throat in a wide curve. She turned away, walking past me over to the midsection of backwall where the water in the lustral basin shone brightly. She knelt by it, washed the dirt and clay from her fingers, sweat of arms, bosom then stood and, standing idly, bowed her head for a second before returning to the fire, calmly sitting down near it.

‘Will you wash?’

I went over upon the softened wooden planks, beneath the polygons and into the light which drenched half the room luminescent blue-violet. The dim pale hue reflected off the floor and water, shone faintly upon the frescoed wall; they were like ancient mosaics with all the cracks and chips in their paint. Kneeling before the lustral basin, thine eyes chased over a frescoed series on the wall of an ancient symposium; its possession a primal, artistically rudimentary beauty - juvenile with an aptitude for artistic flair modernly appreciable. Thus seen in the lofty details of which muscled limbs and genitalia of the persons at an orgy were composed; phalluses crudely plunged betwixt groinal creases, hung limp or stood erect insomuch persons unrobing, kissing prior intercourse; detail of crusty golden flakes upon colouration of regal garb worn by all, exceeding the linear confines of each figure; blue water in ornate pools smudged far beyond interiors; classical fixtures and chandeliers dwarfing rest of the scene; chalices, goblets larger than torsos; women taller than male counterparts, certain power to sight of splayed pelvic regions.

Whence crouching at the lustral basin a moment - the wood beneath soft yet paining knees - I saw dim the glow of my reflection, as well the upper edges of the basin’s immaculate details. I chased my hands upon the rim down to its base, bronze fine and chiselled with myriad indentations, perfectly honed like microscopic metallic granules. The colour pallet deeply texturized, of perfect contrast between black, red, white, gold, blue. There was an inverse octagonal quality to the rim, so that its circumference was flat and smooth, stylized columnar like pillars.

Borne away from my silence, back at the other end of the room came the sound of boiling water. Both hands I dipped into the water, running them over each other within. The basin went deeper than appeared at first glance. I flung and scrubbed some moisture onto the back of my neck and shoulders, rubbed it in to get the sand off. Then used the tips of both index fingers to grate it out from the eyes, in the webs of fingers and ear canals. Lowering both hands into the water I let them stay there a minute, imagined they floated like a body in the sea. Afterward I suspended them over the lustral basin to let the water drip until no more did. Then I got up, parted for the fire, pots, pan, mortar-and-pestle, smell sticks that burned with each tip facing inwardly, smoke one dense plume, the buckets of mussels, oysters and the crone. She looked up at me mirthlessly, though eyes had a certain glint.

‘Cleansed?’

‘You tell me,’ I replied. Which made her smile.

She stirred the crustaceans in a pot over the fire atop a grated rack. The fire raged larger than before, several logs stacked into a teepee. Froth bubbled out, sloughed onto the floor reeking a musty seafood smell. A pan was in the coals with garlic and onion melting into butter, aroma filling our nostrils against the stench. When most of the shells were open I helped her lift aside the pot, take out the mussels. We scooped them onto the pan into the sauce of butter with garlic and onion melted in, grasped the handle of the pan and put it over the ventilated grate. Smoke roared up between the grills, billowed for the ceiling turning to steamy vapour floating toward the windows. Once all was cooked we removed the pan, put it on the stone, started to eat. Many were rotten and we discarded them into the pot; those we ate were stringy, sinewy, tasty with the allium flavour.

‘You look well.’

It was good of her to say so; I was far too young to have eyes lined with crow’s-feet, hollowed deeply beneath in sunken pits. A face gaunt, stripped of flesh and muscle to where the bone, pitted forth protruded rigid, abrupt. Eyes blue, bright that long had begun to darken, lack a quality deprived of substance, for out of them seemed the light had gone. Despite all that the sun had done its own number on me owing the languorous heat of midsummer.

‘Thank you.’

The crone smiled meekly, ‘Did the sea teach you very much today?’

‘What could it teach me?’

‘Quite a lot; if you listen and watch it will tell you things. Sea works such magic: to help you understand in new ways you never thought nor sought.’

‘Do you learn from it?’

‘Yes, of course - often in youth but not so much now. Every while it still speaks to me, indeed. Though nowhere close to as much as it used to do.’

‘I see.’

‘Not for you - it’s never spoken?’

‘It hasn’t told me anything, otherwise I haven’t listened well enough.’

‘No? This is understandable. For it is a skill which must be learned. Not anyone can truly listen to the spirits of the sea, songs of tides and swells lament to the moon. Nor can all see and be aware the secrets of fish, their societies, or the cycles, flows-ebbs and institutions of all which makes up the sea.’

Plucking a final mussel off the plate it was cold, tougher without moisture. Parting the opening of shell between finger and thumb, I locate and tear it out with teeth. Licking garlic and onion juices off my fingers I could not help smiling. A smile flits her lips, grows weaker until it is gone. Soon eyes hone as if controlled by gauges of a telescope; like she remembered a task to be dealt with, would not rest until it was appeased.

Two orbs of liquid glossiness flicker into the back of her skull, between white flashing dark, become enclosed by their lids. She got up, tread to the lustral basin, knelt beside it, head rested flat on sinewy wood, limbs gone limp, prostrating length of body aground. When she comes back up takes a breath, idles on knees, hands motionless beside legs. She starts speaking in Greek, in a manner which seems more incantation than practical speech. The crone’s head bobs gently, back, forth with slow motion of geriatric in rocking chair, volume increases as she channels spirits, depth of voice rising, rising. Through its entirety mutters in Greek, mixing in words and phrases of even more ancient languages unrecognize. There was ferocity to the voice, fanatical yet mesmerizing. At the end of liturgy she dips both hands into the cold waters, washing herself once more. Then she comes back over, sits beside me.

‘What were you saying?’

‘I was giving thanks to my gods,’ was her answer.

‘The polytheistic?’

‘Yes, them. Do you hold faith?’

‘No.’

‘Not even one god?’

‘None.’

‘You’re tired today. Hot sun. Long days.’

‘It’s a lot different than where I come from.’

‘Without the freeze? Something I’m happy always to have done without throughout my advanced years. Do you miss your home?

‘A bit all the time. Other than that, it goes alright.’

‘I could not do without mine own.’

‘A place unlike any others. Bound by different degrees of substance, elixir. Verily the stuff of mythic legend, might I add.’

‘See now that you’re learning? Indeed, sea has taught you it is best to be by, better is best of all never to leave.’

‘Yes,’ I allowed. Grinned vaguely.

‘Yes, indeed.’

‘May I ask you something?’

‘Of course.’

‘Do you really believe in your gods?’

‘I believe it’s important to honour something, that worship even is justified given proper dogma for practical codes.’

‘So, you believe in the ideals of right and wrong?’

‘It’s more, because a part of me believes wholly, yet I remain skeptic; another is convicted, as you say, because of moral and ethical considerations.’

‘There’s a part of you which believes without a sole doubt?’

‘There is, yes.’

‘Another isn’t sure or is because of necessity for righteousness?’

‘Yes.’

‘Could you explain it more?’

‘I cannot.’

‘Okay - what for of that prayer?’

The crone took in a deep breath, smiling mawkishly as if I were an ignorant child, and began, ‘No longer in the summers are we able to offer prayer at Delphi, or on any of the sacred isles. Nor now can we speak to oracles for wisdom. And so every half-year past, at the point in summer exactly six months until, for us we say, for the season that is farewell to the unconquerable that shines o’er perpetually, thee Unconquered which lights our way, I perform personal rites here as mine own custom.’

‘It’s very interesting to me.’

‘Yes, easy to be impressive in a world where everything we were meant to be or know was put before us, everything meant to follow sculpted out in place - what they called convenience, commodity - for sake of normality.’

‘It feels wrong to discuss political things here.’

‘It’s not a thing political. It is of war; the battle in each of us.’

‘That may be right.’

‘So, there is more.’

‘Of what?’

‘More in you than is revealed the five senses. More of you; I see it in through the eyes. More than is let on through your silences. More that lies beneath your veil of sight, that beckons you, keeping tethered.’

‘Alas, tonight of all nights your riddles have subdued me.’

‘What is it on your mind?’

‘Nothing,’ I told her.

‘As in vacuity, or nothing when there’s actually everything?’

‘Yes, both.’

‘Which!?’

‘Must an answer be definitive?’

‘By Zeus - yes!’

‘Then option two: nothing yet everything.’

‘As I thought, you’ve felt this way often. Sometimes I can see it, burdens buried in subconscious.’

‘From time to time.’

‘Most times, I believe.’

‘Who are you, hell?’

‘I am many things.’

‘Do you always know how people feel?’

‘It is a great skill to learn and manage; if one truly knows themselves and allows Tao they know others as themselves, through reflections and projection.’

‘Through the eyes: each other inflected.’

‘What?’

‘Something I wrote once.’

‘You’re a decent young man - there is much to you I think byway of intelligence, depth, insight.’

‘Thank you.’

‘Are you more exhausted, now than before?’

‘Yes, indeed.’

‘Go for bed, Henry. Don’t let me keep you.’

‘I think that I shall.’

‘Sleep well, man of cold northern winds and snow.’

The incense had all burnt out, the room become mustier, smoky. As I stirred the crone began to stack the plates, gather each ritual object; I collected the pots and pan, intending to take them out myself. She insisted upon otherwise, convincing me to leave them there. So I got up, went over to the lustral basin, kneeled, washed the cool water over my skin once more.

‘Goodnight,’ I then said to her, cleansed of dirt, feeling pleasantly cooled, moist.

By a subtle wave she bade farewell; I went up the slab steps, out of the cellar, into the chamber. Going beyond heard water pouring onto fire, shadows stiller as before where she was as I left the sunken cellar, where she had been when I found her.

About the Creator

James B. William R. Lawrence

Young writer, filmmaker and university grad from central Canada. Minor success to date w/ publication, festival circuits. Intent is to share works pertaining inner wisdom of my soul as well as long and short form works of creative fiction.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.