Fueling the Stars

Antimatter Propulsion: The Future of Interstellar Travel

Among the many concepts envisioned for the future of space exploration, antimatter propulsion stands out as both the most theoretically powerful and the most technologically demanding. It is a concept born at the edge of physics and engineering—one that could revolutionize how humanity travels through the cosmos.

While still in the realm of experimental physics, antimatter propulsion represents a radical leap beyond conventional rocket technology, promising unprecedented speeds and efficiency. The principles behind this idea draw from the very fabric of the universe: the fundamental relationship between matter, energy, and the structure of particles.

---

What Is Antimatter?

To understand antimatter propulsion, we must first understand antimatter itself. Antimatter is a form of matter composed of antiparticles, which are mirror images of the particles that make up regular matter. For example:

The positron is the antiparticle of the electron. It carries the same mass but has a positive charge instead of a negative one.

The antiproton is the opposite of the proton, possessing a negative charge.

When a particle and its corresponding antiparticle come into contact, they undergo mutual annihilation, converting their mass entirely into pure energy. This is no ordinary chemical reaction; it's governed by Einstein’s iconic equation, E = mc², which states that even a small amount of mass can release an enormous amount of energy.

This reaction is incredibly efficient—far more efficient than nuclear fission or fusion, and orders of magnitude more powerful than chemical combustion used in today’s rockets.

---

Unleashing Immense Energy

To grasp the staggering potential of antimatter propulsion, consider this: the annihilation of just one gram of antimatter with one gram of matter could release about 90 terajoules of energy. That’s equivalent to approximately 43 megatons of TNT—nearly 3,000 times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

This kind of energy density could dramatically reduce travel times across the solar system and potentially enable interstellar missions. For comparison:

A trip to Mars, which currently takes 6 to 9 months using chemical rockets, could be reduced to mere days.

A journey to Pluto, which took NASA’s New Horizons probe 9.5 years, could take less than a month with antimatter propulsion.

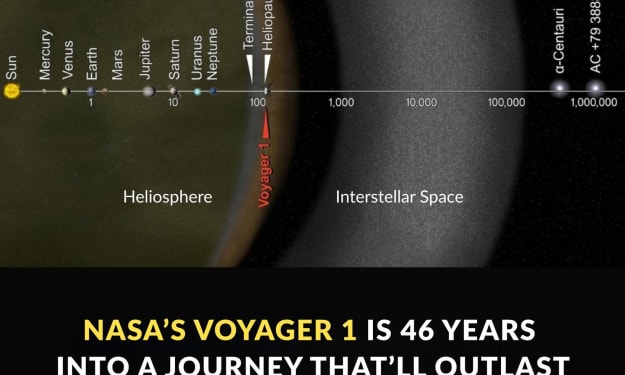

In theory, even Proxima Centauri, the nearest star system to Earth at 4.24 light-years away, could be reached in decades rather than millennia.

Such a propulsion system could fundamentally change the scope of what is achievable in human space exploration.

---

How Would Antimatter Propulsion Work?

There are several proposed designs for how antimatter could be used in a propulsion system, each with varying degrees of feasibility:

1. Direct Annihilation Drives:

This concept involves directing the energy released from antimatter annihilation directly out of a spacecraft to create thrust. However, the process releases high-energy gamma rays, which are extremely difficult to control and dangerous to both crew and equipment.

2. Antimatter-Initiated Fusion:

In this model, small amounts of antimatter are used to trigger a fusion reaction in a more easily managed fuel like deuterium or helium-3. This approach would combine the efficiency of antimatter with the relative controllability of fusion, potentially offering a more stable and safer means of propulsion.

3. Positron Propulsion:

Instead of using heavier particles like antiprotons, some scientists propose using positrons, which are more readily produced. While not as energy-dense as antiproton reactions, positron propulsion might be easier to handle in early applications.

Regardless of the method, all designs face the same fundamental challenge: safely storing and managing antimatter.

---

The Challenge of Production and Storage

Currently, antimatter is one of the most expensive materials on Earth. It is produced in tiny amounts at facilities like CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) using powerful particle accelerators. According to NASA, producing just one milligram of antimatter would cost around $100 billion. At current rates, humanity produces only a few nanograms per year.

Even if cost were not a barrier, storing antimatter safely is a major engineering hurdle. Since antimatter will annihilate upon contact with any matter—including the walls of a container—it must be suspended in magnetic or electromagnetic traps, such as Penning traps. These systems use powerful magnetic fields to keep antimatter particles floating in a vacuum, avoiding collisions with physical surfaces.

But these storage methods are energy-intensive, fragile, and not yet capable of holding the quantities needed for propulsion.

---

Research and Future Prospects

Despite these monumental challenges, research into antimatter propulsion continues, driven by organizations like NASA, ESA (European Space Agency), and private think tanks. Several papers in journals such as the Journal of Propulsion and Power have explored potential designs and long-term feasibility.

NASA’s Institute for Advanced Concepts (NIAC) has even funded studies on antimatter-based propulsion, including hybrid systems that could initiate micro-fusion explosions or power ion drives. These hybrid approaches are seen as stepping stones toward more advanced systems that could one day support manned missions to outer planets and beyond.

Moreover, advances in magnetic confinement, miniaturized accelerators, and radiation shielding may make antimatter technology more practical in the coming decades.

---

Implications for Humanity

If antimatter propulsion becomes viable, its implications for space exploration are profound. It could allow for:

Routine travel to the outer solar system

Fast, efficient crewed missions to Mars and beyond

Exploration of exoplanets and star systems within a human lifetime

A paradigm shift in interstellar communication and colonization efforts

However, it also raises ethical and security questions. Antimatter’s immense energy density makes it a potential weapon of mass destruction—far more devastating than any nuclear device. Strict international controls would be required to prevent misuse.

---

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.