Dirty Letters

By David Tyrer

The letterbox vomited an excrescence of dirty white paper onto the mud-clotted doormat of Arthur’s freezing cottage. When the last fillet of bad news had fallen, it snapped back into place on a muted low note. The disturbance tore him rudely out of his dreams and into rough, sweaty bedsheets. Next to him, his raddled wife dreamed on selfishly. He could smell the cold morning air seeping through their half-open window. Bad news. Arthur knew it could hardly be anything else.

“Tax, bills, payments,” he muttered out the holy trinity, feeling the pop and crackle of his aching body as it tried to assert itself into an upright position, “Utility bills. Arrears. Pizza adverts. Doctor’s letters. Doom and despair.”

It wasn’t just his body going this morning; his voice had taken on a sinister, phlegmy quality he didn’t recognise. Cancer? Wasn’t everything, these days? Nah, lightning didn’t strike the same house twice. Staggering to the curtains, Arthur pulled aside a few inches of stained net to look out on the yard. Yeah, about right for February; grey, dull, frozen. Countryside laid bare, all rusted tractor parts and dirty hedgerows. The genteel bit of England. He ought to get round to the hedgerows. He ought to see His Lordship about them. There was the postman, walking away a few bills and worries lighter. No, Post woman. Whatever you called them. Did it matter? He watched her scurry down past hay and chickenfeed, corrugated iron and unimportant cottages. Anxious to get to the Hall, probably. He couldn’t blame her.

“And good fucking luck, chum,” he muttered, watching her red van roar out of sight. He waited until the last blue wisps of petrol had stained themselves into the atmosphere. Steeling himself. Some poet had said you needed to stand and stare sometimes, and that was true, thought Arthur, but you could only do it for a moment. Then you had to face the music.

By the time he’d put the coffee on, splashed some cold water on his face (no need to shave, who’d see him) and put himself through putting on all the warm winter things, he thought he could just about face the thought of the letters. There was a proper thrill of dread when he strode wincing over to his wellingtons and saw them all; piled high, with angry-looking red scrawled across them. The cherry on top was a parcel, crumpled and rammed through with some difficulty. Well, if it was the next batch of Doxil, they needn’t have bothered.

“Fuck off,” he told them challengingly, “you can wait, you.”

“Talking to the mail again, dear?” his wife called out.

“Yer,” he bellowed hoarsely, “Five things we got today, Lil. Five. Fucking cheeky, that is.”

“That’ll be bills, that’ll be,” she told him unhelpfully, her voice slightly muffled with sleep and pain. “Be bills that, Arthur. You’re using that kettle too much. Just stick it on the fire. No-one charges you for fire.”

“Can’t stick it on the fire,” he told her with some disgust, “it’s electric. Got all parts in it and that. I’ll do that when you stop turning all the main lights on. We’ve got side-lights, use them.”

“I can’t read Richard Branson with side-lights,” she wailed mournfully. “Now there’s a man who made the most of what he had.”

There was no point in telling her, Arthur reflected, that Richard Branson had quite a lot to start off with. You couldn’t come from nowhere without at least having a bit of somewhere stuffed away first. Parents, now. Parents would have been a help, but both theirs were either mad or dead.

“I’m putting the kettle on, then,” he told her desperately. Perhaps that would leave a few more minutes before he’d have to open anything.

*

The third whiskey burned through Hamish McCullen like scarlet fever. A nanosecond of utter fear and panic, then violent elation; bliss. He ought to stop thinking about it. He had to put anxiety out of mind. He would bully the girl behind bar, he decided. That always cheered him up.

“Service at last!” he roared, slamming the crumpled note against the counter with violent and affected joy. “Give us another one, will you?”

The little tart jumped back several paces and complied, scared out of her wits. Change jingled in the humiliating felt pouch she had to wear.

“Good measure there, though,” he complimented pitilessly, picking up his fresh drink. “Bloody good the way you lot come over here and spend your time pouring pints. You on a gap year or something?”

“Study,” she corrected his fatuous assumption

“Study, eh? Bloody good thing, your country,” Hamish decided, ignoring her completely. “Absolutely no civilised places anywhere. Total level playing field. A real good deal, that. It’s rather a struggle having all these generations of history to carry around, yaknow? Don’t let anyone tell you a big old house is a good thing,” he drained the glass (his fourth) in one impressive swoop, “fucking nightmare.”

“Is that right?” No money was worth this, Judie thought, mopping up the sticky, sour-smelling mess he’d left on the bar. She’d left Brisbane on the hopeful sentiment of studying Eighteenth-century architecture and the crumbling relics of the old world. She’d found a lot, but tragically quite a lot of them had turned out to be ideas, or people.

“Oh, yeah. That’s pretty much why Dad left.” Pretty little thing, Hamish thought appallingly. Five years ago he’d have tried to bed her, but at Thirty-seven one ought to be just over the cusp of picking up teenagers, Australian or otherwise. He knew he was no oil painting anymore; the healthy, slightly desperate glow that rugby and other more vicious pursuits had granted him had almost entirely been consumed by a love of red meat and overpowering alcohol. Conquests were now either freshly divorced and vulnerable or else the kind of halfwitted spinsters that filled the chairs of society dinners and were only too willing to stagger up the winding stairs long after everyone else had seen the sense to shove off. Still, he thought bitterly, a chap couldn’t have everything. Thinking of not having everything brought him straight back to the thing he really wanted. Where the bloody hell was it?

“That must’ve been hard, your dad leaving like that,” Judie told him listlessly.

“Terrible. Trying to get the estate sorted has been a total headache. All those brave old retainers. Still, got to clear away all the dead wood,” he sniffed, totally unaware of the seven angry pairs of ears that picked up that throwaway remark. “And the paperwork-d’you know how much in legal fees this whole thing has cost? Makes a chap almost question…”

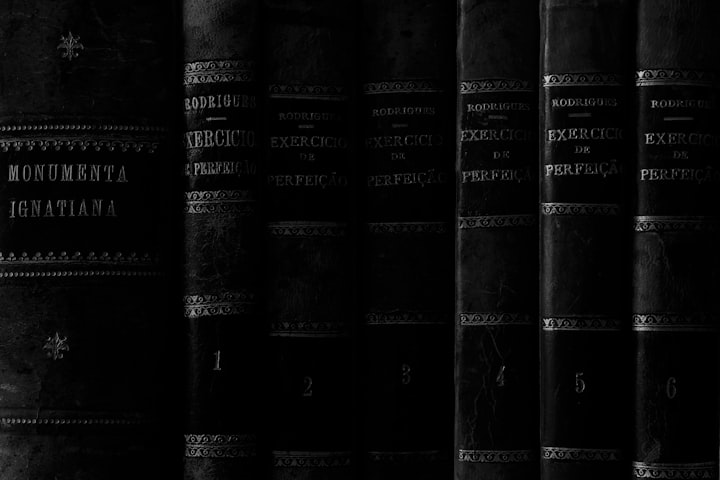

Well, whatever he was about to question, it all came back to the same thing. The book. A neat, black little number with the future of the land in his name and a (to other people) quite horrifying amount of money attached to it. He remembered sitting in the dusky, red-lined rooms, pouring Belgian brandy from the decanter and toasting a venture he could half care about, so long as it got him out of the fucking countryside. Had he given the right address? Did it matter? Everything was his, anyway, fuck Dad and whatever he might complain about. He’d hammer on every door of those wretched cottages until he found it, or else sack the post office. That’s what the McCullens of old would have done, savages though they were.

“Are you moving out of the estate?” Julie could give less of a shit whether she saw him again; no-one liked younger McCullen, metropolitan usurper of the old Gent, but quite a lot of lives in the town were tied into the service of his ailing family. Also, there was the not-entirely unselfish hope she’d finally be let in by whoever took over. There were gargoyles and buttresses about the old pile worth a sketch or a rambling dissertation on.

“Eventually,” he confirmed, before casually crushing her with “about the time we knock the place down. Ghastly old place, yaknow. Ever tried living in history? It’s horrifying. And draughty. One keeps expecting the dead for dinner.”

The old Gent, Hamish reflected, had lived in history quite comfortably, for all the good it did him. There had been the subtle expectation that the son would, over time, grow to love the tedious, antiquated feudal worthlessness of the father. Hamish had soon put him right on that. He wasn’t a farmer, or a lord. He was a businessman. He had a flat in Chelsea. He went to parties. The country held no charm for him, aside from the vast potential it could have in being turned into a biking track. He didn’t know country people, but he did know city people, and a team-building retreat of some kind would always appeal to the wealthy enough and empty enough to think it would help them bond.

“Don’t suppose you could pour me another, could you?” he drawled, indicating the filthy rim of his glass with a stubby red finger. That was the answer, of course. Rather a lot for one night, but fuck it, he’d been kept waiting by something. That never happened. In a while, he’d stop thinking about stupid things like addresses, dates and so on. Someone was bound to check it for him.

Judie gave him another thick, syrupy measure, feeling an empty, divorced kind of pity for the wreck of English aristocracy in front of her. Everyone knew about the deal, even the postman. He’d been stupid enough to gloat about it, and with Lilly the way she was. The way she saw it, stranger though she was, it was going where it was needed.

*

“Well,” Lil stared at the contents of the letter. “Well.”

She’d said it a couple of times. You could get a lot of mileage out of that word, reflected Arthur. There were some things the human brain had difficulty getting round. The little black ledger practically shone among the coffee-rings and chips on the kitchen table. He re-read the roughly-scratched note pinned to the parcel, and checked the money again.

“Dollars,” Arthur told her uselessly, his mouth going dry.

“I mean,” Lil tried to find the words for it, “that’s more than I get off my pension a year, twice over, isn’t it?”

“Yeah,” he confirmed. Single word responses were about all he could manage. Bills, treatments…you could cover all of them with one tiny drop of it, and still have enough left.

“Enough left for what?” he wondered aloud.

“We couldn’t keep it,” Lil decided hollowly. “We’d have to send it back to him.”

“Would we? Why?” Arthur asked. “Would he miss it?”. A picture came to him so clearly he was half-living it; sitting with her of in the soon-to-be final months, curled up uselessly in some futile waiting room somewhere. Holding her hand while she withered. And all of it for the cold comfort of being good and having forty years of hard graft being paid back with shit.

“It wouldn’t be enough to last forever,” she told him sternly. It was a good thing, Lil being stern. It meant you were getting under her skin.

“Enough to get us abroad. Enough to get you somewhere sunny. It’d all be legal, anyway. Cash for services rendered. And then-“ his voice caught. He would think about ‘then’ when it came. But everyone needed a gardener, even an old one. Bones be damned.

“I’m not leaving you to rot, Lil. Look around you; he’s taken everything, the mansion, the farm-it won’t even be a fucking farm anymore, we stick around. He’d have turfed us out anyway, off to some miserable little rainy flat in no-where. How’s Barbados sound?”

“What’ll happen to you?” Lil asked. She felt breathless; somewhere, happiness started to dawn like sunshine on a late winter morning.

“What happens to everyone, eventually,” Smiled Arthur. “Get your stuff together.”

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.