Aging Time

A Short Story About Trauma & Growing Old

Leaving the warehouse was something he’d always expected to do. At the end, forty-five years of it, he never had. This morning, another arduous day come would just as surely go, he filed into the megastructure amidst the silence of every other worker. Their legion came from regions far and wide for the dawn shift, fleeing fast out of the dark bitter winter twilight; heavy safety boots smacked the pavement, breaths misting in the air. Soon the automatic doors swung open, ushering inside the tired silhouettes. Hacking throats that betrayed smoke-choked lungs, fingers tossing cigarette butts. Assembly herded within.

Each day. First thing the gates would open, then they’d all go inside. Each and every day. Both the green who as of yet knew not languish and those who’d long toiled, skeletal zombies from the trade, weathered journeymen to suffering, of lungs coated black from dust and chemical inhalation throughout the years, bodies crippled permanently under weight of the machines, hopes and compassion dulled to soured mettle from the culture of neglect, maltreatment, indifference, the herein taken for granted hours endless endured.

-

He’d always known his life never was going to be a florid story, simple as he wasn’t a rosy person. Cheerfulness was something, if ever he’d had, beaten out of him long ago. A child who’d only known a steel-fisted father with an iron mind and a subservient wife. That which had forced him, if he were to make it through and have a chance, to have an iron will. Chances flew the coop long ago too, a good while before he’d noticed, prior to his last days of education in grade ten, whence from various vicious psyche scythe wounds his stock turned rotten afield, a harvest stricken by poor conditions and drought, weaker will at his father’s fists and final word.

Often in his youth he’d fancied himself a wilted flower. He saw the irony, most alike the father in the occupation of the mother. That brought a wry smile in the earlier times and only a grim tick of the mind later on. A face wrought of his father’s. Bronze broken. A chip off the old block. And in life, just like his mother. Just like her. In service to a domineering beast who neither respected nor appreciated the labour he exerted, merely to make a life. And like her too weak from oppression to have had the gizzard to do anything about it, at least back when it still mattered. His mother had died over a decade ago, his father, more than two.

In the forties his father had been an enlisted man serving in an infantry division stationed in France. He was among few in the service called on at the earnest start of it in 1940 to ship out and who, for lack of luck and survivability, did not return until it all finished. As a young boy his mother told him that when they finished school, before the war, were helping the family on the farm and married, his father had had quite a cool demeanour and a temper that only flared up if it was upright necessary. When he returned almost six years later his son was five, necessarily upright came far too often and the thought or discussion of conventional things made him sick, which nigh always translated into wrath or delusion, although his mother unequivocally expressed that it was their duty to be upstanding for the man who tormented them.

Glen visited his mother, Mary, twice in the late days of her life, once for an afternoon on her birthday a few years before she went, and for the last time when she’d fallen on her deathbed in the hospital of their bygone hometown. Somehow, despite the unsightliness and sickly smell he’d felt much affection for her then, hours before she passed, a love in the manner he’d bore her as a child the times before the man came home, when she was really a mother loving, untorn.

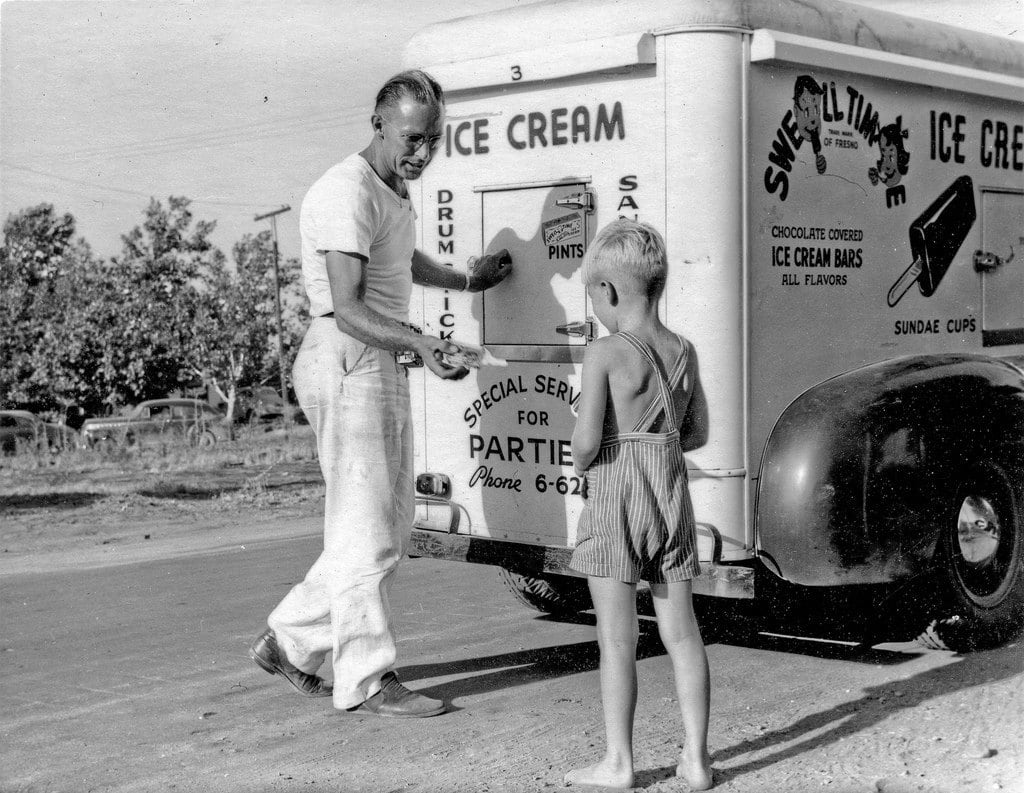

Their worst experience had transpired an evening when his father had seemed rather encouraging and talkative, still Glen was very young, the man was opening up about Europe until later he’d become grim no longer wishing to discuss it. The boy, who was young, also was ignorant and byway of one mistake, became no longer a boy. That was the first time things actually got significantly bad. And on the front porch as well, for better or worse. Then also mother had made the mistake of interjecting herself and for her, without a shade of doubt, it was ten times worse, as it near always went. This was why he was able to still love her somewhat, remembering how he’d seen her delicate skull thudding the bannister or her back imploding down the stairs. He loved her for the times she put her son first in lieu of the monster they harboured. Upon that first exposure, it’d been a summer evening of languor, the neighbourhood families and children outside, strolling, cycling, ice-cream trucks in tow, many having a drink and smoke on the porches. They never learned who called the police, yet really it did not matter. When the officers who’d reported to the disturbance returned the man home the following evening, it was permanently bad then on out. The old soldier became less a shrapnel of the man he’d been than a faulty fuse that expedited the simplest spark. Some spring, in the fifties when Glen skipped town, it was the irony that lasted and impressed upon him the most ever after. In terms of demeanour, he’d soon become fully the old father, not the kindly mother who remained stout throughout hundreds of domestics. For no other reason he loathed more about himself than he could realize, and for the memories of when he’d ran away at the sight of his mother cornered alone; also that he’d never welcomed Mary to meet the babies that were her grandchildren, nor sent an invitation for her to attend the wedding of her only child, neither wrote nor rang or visited her. The man, Philippe Henri, he never saw again after that fateful spring.

If things had been different, the thought he’d had to force out of his head every day over the last forty-five years. Time wouldn’t allow it to be such. I was kinda smart, maybe I could’ve gotten on with science and worked in a lab or been a doctor or invented new methods for treatment. Time that was never enough. I was mighty fast and good at hockey, I could’ve been an athlete. Such was never willed. If things could’ve just, might’ve just been a little different. How could it be? Never capacity for the big questions. I remember times that it felt things were starting to become a little better, hopes that mother might leave. Yet she never did. Forsaken portraits that never were painted. In life, those who get destroyed by it become other.

Now forty-five years, Glen had worked in the warehouse a gruelling forty-five years. For the last thirty-five it’d been on a forklift. Five days weekly, round the clock. Subservient for the sake of societal security. Working to stay alive. You saw the others who didn’t. Truly it was easy enough to imagine what’d happened to them. Maybe some were like him when they were kids. Splintered mosaics who never scrapped back the pieces, or the veneer of such. Now ghost minds inhabiting phantom faces and husked shells, wandering the streets for a scrap of meat or crumbs, a cardboard box to lay down on and a new pair of tatters to change in to. For what differences he told himself made them stranger to him, he’d known in his heart he was mostly as homeless as the poor vagrants who phlegmed up downtown, back-alley avenues of their modern community.

The stranger stared back at himself from the mirror setup in the lift. The jowly neck lined like the haunches of a wildebeest with the taut, stretched indents, a stress bald head and face that was seldom often not beet red, the wrinkles and crow’s feet and bulbous veins. Glen didn’t recognize the eyes etched in that mask anymore – hadn’t for time immemorial. They were by-products of soil and decay, buried in crevices and dried-up to some depth. Normally he didn’t bother looking at himself nor fixate upon how he appeared – wasn’t worth the thought.

Most the friends he’d ever had had come and gone, many of whom were dead or retired, well on the way into their senior years and towards death. One thing particular, what never ceased was that the new faces were endless. Some even shone bright the early days before the mindless smiling settled into grimacing, as the motor functions of the bodies and hands settled into discomfiture of habit, body-mechanics faltered into an ease of pace, repetition, the postures slacked and attitudes frustrated until they too moved on away. He told himself the young didn’t know how to pay their dues, that none wanted to honestly work hard anymore, but deep down believed all of them were best off leaving from the place where one who stayed could only meet a final desolation. Tedious corpses frosted over with gangrene and fiery freeze.

Glen parked his machine in its docking station and patted off his dusted carcass. He hacked and wheezed from the gunk that had long settled invariably in his gullet. He stood there idle for a long moment, waited for something. In feeling. It came, the sentiment, took over rapturously until for the first time in decades he could’ve cried. Instead, he reached in his pocket, fumbled about and took out its frozen-in-time semblance.

Time was the ficklest of bastards, and as it past by, you could never catch it before it was gone. To be wealthy enough in riches didn’t hold a dime to the poverty of what he lacked, love he’d neglected to fight for. Time was unkind, unchangeable, eternal – each thought turned into word into sentence was dangerous as glass. Every yelling shouting time that he’d raised his voice a frigid pill he couldn’t take back, that he wished dearly to ingest and swallow so as to hold within the pain he’d inflicted on those he dearly missed.

For the first time in a lifetime he felt purpose. Martha would take his call, despite being divorced, despite his drinking, despite past, she always did. She was a fine woman. All that was done today, anyhow. He had childhoods to make up for. In the pictures they were, his two daughters, freckly and pimply teenage girls, barely any younger than they’d been the last time he’d seen them. The most precious things he could ever imagine. Martha’d take his call. Good lady. He knew she would. That much he deserved.

‘There you are,’ called a voice from the wire-strapped pedestrian aisle at the entrance of the industrial complex. A man, middle-aged supervisor was strutting towards Glen in his rubbery metal machine. ‘I hoped I’d run into you. It’s the last day, after all.’

‘Well, you see me,’ Glen said, mustering a grin for the oncomer. ‘What’s the fuss?’

‘Listen, old man,’ spoke the younger overseer, halting across. ‘I have the right to tell you it’s been an honour getting to know you, it’s been a hell of a time. So thank you.’

‘Don’t sweat it, I know I made your early days hell.’ Glen paused. ‘I’ll make sure to send you an email once I find footing in being old.’

‘You do that.’ The man reached up, they shook hands then stood apart. ‘I’ll be seeing ya.’

‘Be seein’ ya, Barry.’

‘Thanks for being one of the good ones,’ the man said, before starting off into the light-polluted warehouse. Glen watched him there as he went. Then he clocked off, plugged in and stepped down from the machine.

‘Here’s to aging time,’ he said under his breath.

The End

About the Creator

James B. William R. Lawrence

Young writer, filmmaker and university grad from central Canada. Minor success to date w/ publication, festival circuits. Intent is to share works pertaining inner wisdom of my soul as well as long and short form works of creative fiction.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.