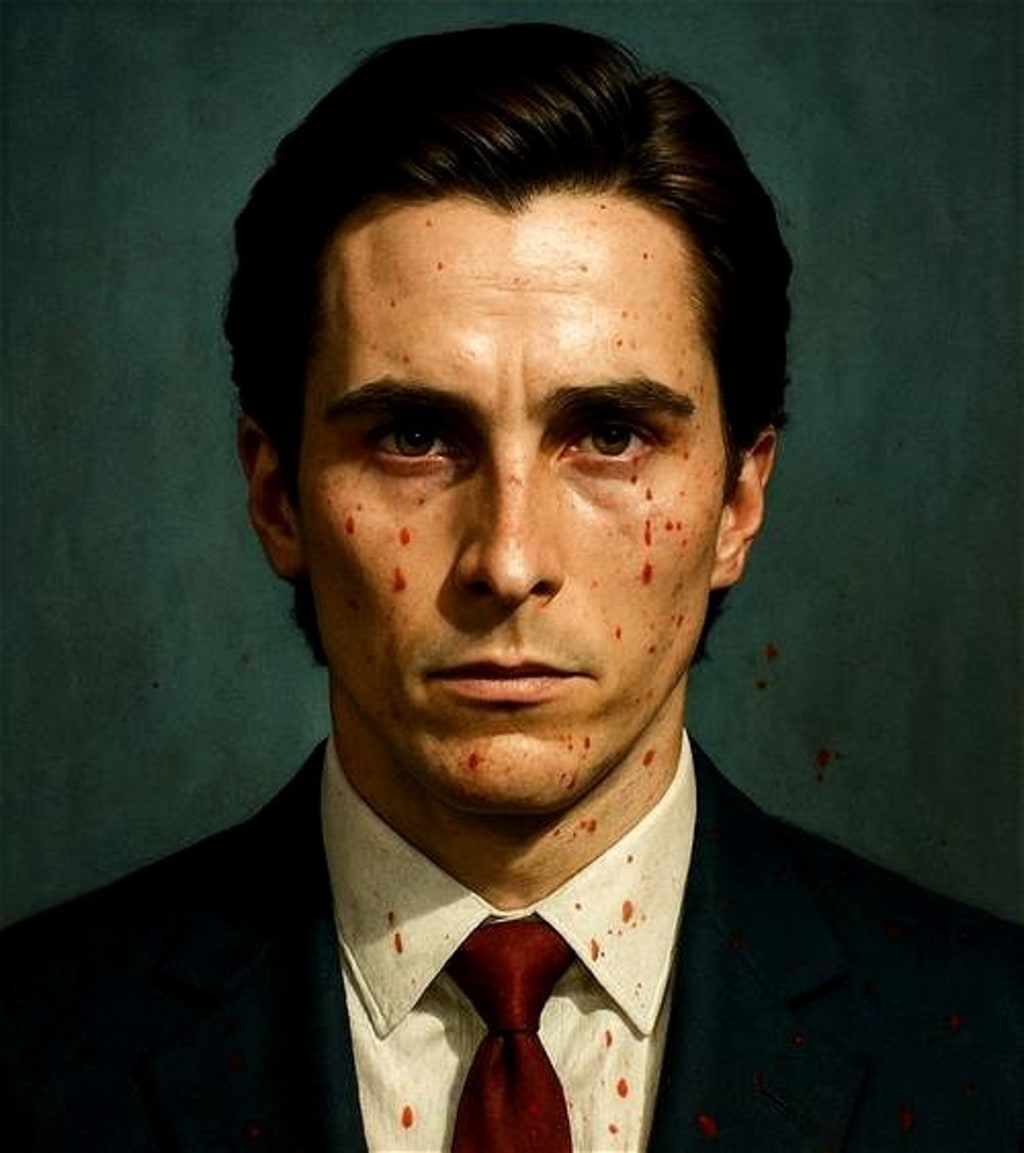

Why American Psycho is the Philosophic Doctrine of the Modern Dystopic Nightmare

A transmission from the land of perpetually deformed surface illusions.

I should preface this by stating that I am nothing like Patrick Bateman. I am not wealthy, handsome, or socially graceful (although arguably, Patrick isn’t either), and—most importantly—I am not a criminal or a killer. Under the right circumstances, of course, everyone can become a killer, but that is not the point here.

American Psycho, the novel as well as the movie, is a very important—perhaps even milestone—piece of literary art. It strips back the layered mask of a man who is drowning in material wealth and sexual conquests and reveals that, deep within that man, is a monster. It contrasts, jarringly, his obsession with name brands, designer fashions, stereo systems, and the hottest nightspots with sickening, rage-fueled violence. It's a whirlwind dip into the ocean of existential nihilism.

During the first few scenes of the film, as Bateman insults and threatens a barkeep at a dance club while her back is turned (as New Order's incredible song "True Faith" plays in the background), we feel a sense of the weariness of the character—that he’s wearing his world like a costume, a well-designed outward "mask of sanity" hiding deep within a void-like, blood-drenched monster. A creature with a yearning to find reality amid all the surfaces, all the phoniness and glitz, all the prefabricated and commodified exteriors he can buy or, chameleon-like, con his way into. And the viewer understands him, in that moment, as a figure perhaps wandering a self-created wilderness in Hell.

His exposition of his own remarkable yet also banal life—the interchangeable “friends,” his multiple affairs, and his romances that are little more than window dressing for a persona so psychopathically detached he can alternate between “concern” (or the masquerade of the same) for his cohorts and sickening acts of sadistic violence—and punctuate it with an entire chapter noting the relative features and functions of his quadrophonic stereo system. That dialogue is laced with obsessive notation of brand names and labels of high-end fashion, electronics, and consumer goods.

Bateman lives in a world where everything, even human bodies, are collections of interchangeable parts, each functioning separately even as they work together to form the tapestry of a world he slips into like the gloved hand of a strangler.

The physical symptoms of the “world” demonstrate it as a place of hollow sympathies—Bateman goes through the motions and gives lip service to causes that even contradict themselves. (He wants to promote predatory capitalism while simultaneously promoting “less materialism” and a return to traditional values.)

The novel by Ellis, written in the late ’80s and early ’90s, prefigured the social media revolution, in which millions show their advocacy of any number of causes and positions by clicking a “like” button and receiving the resultant dopamine hit like a rat receiving cocaine-laced cheese in a laboratory experiment. None of this advocacy is particularized or “real”; none of it is genuine—except inasmuch as the user of social media has selected a particular viewpoint and needs the psychological reinforcement of the same.

This is the same yearning Bateman feels as he effortlessly navigates a world that stares blankly at his aberrant behavior, noting it with no less indifference than they do his slick, charismatic persona, which ingratiates him to them. He can, in point of fact, utter the most monstrous invectives, and all around him seem to mark them with increasingly bizarre ambivalence.

He is obsessed with the commodification of violent entertainment and sport—talk shows replete with tales of abuse, cheap video entertainments on fellow serial killers, tabloid junk food—filler and fodder for the human brain.

Oliver Stone’s film Natural Born Killers satirizes the media landscape wherein bloody sport and mass-casualty murder sprees are simply another ratings gambit for supremely cynical media wolves in sheep’s clothing.

Bateman tries to find an identity, a sense of spark, in the bland surface of his world. The gnawing beast at the core of his being is sated—or perhaps aroused would be the better term—by Ballard’s “neural landscape” of slick advertisements and cheap, violent, erotic stimulation. This is what he prefigured or foretold in his unerringly opaque experimental classic The Atrocity Exhibition, which—besides Crash and American Psycho itself—qualifies as a triumvirate of essential postmodern reading for truly beginning to grasp the terminal malaise of the modern age.

Read my first article on American Psycho:

Slipping the Lizard Skin

We behold the sickening deformation of the lizard skin of modern, post-atomic, post-cybernetic, post-nihilist world culture—the shared experiential nightmare of our lives, fragmented and atomized as they are, controlled by electronic and cybernetic forces push/pulling us in Orwellian fashion toward the nihilism of modern dystopic identity.

And Bateman is a hollow man. A solipsistic personality. A void ego wondering at its own reflection as it peels back its skin in the mirror. Narcissism made whole as a man.

To slightly quote the line from the New Order song played in the film (which seems to me to be a spiritual theme to the work itself): the singer doesn’t care, because “I’m not there.”

And Bateman says, also: “I simply am not there.”

He isn’t any more certain of his “reality” amidst the illusion than he is of the parts that constitute its boring, banal, and false whole.

He is not there.

And, to quote the final line of the book:

“This is not an exit.”

American Psycho (2000 Movie) Trailer - Christian Bale, Justin Theroux, Chloe Sevigny

On X (formerly Twitter): https://x.com/BakerB81252

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.