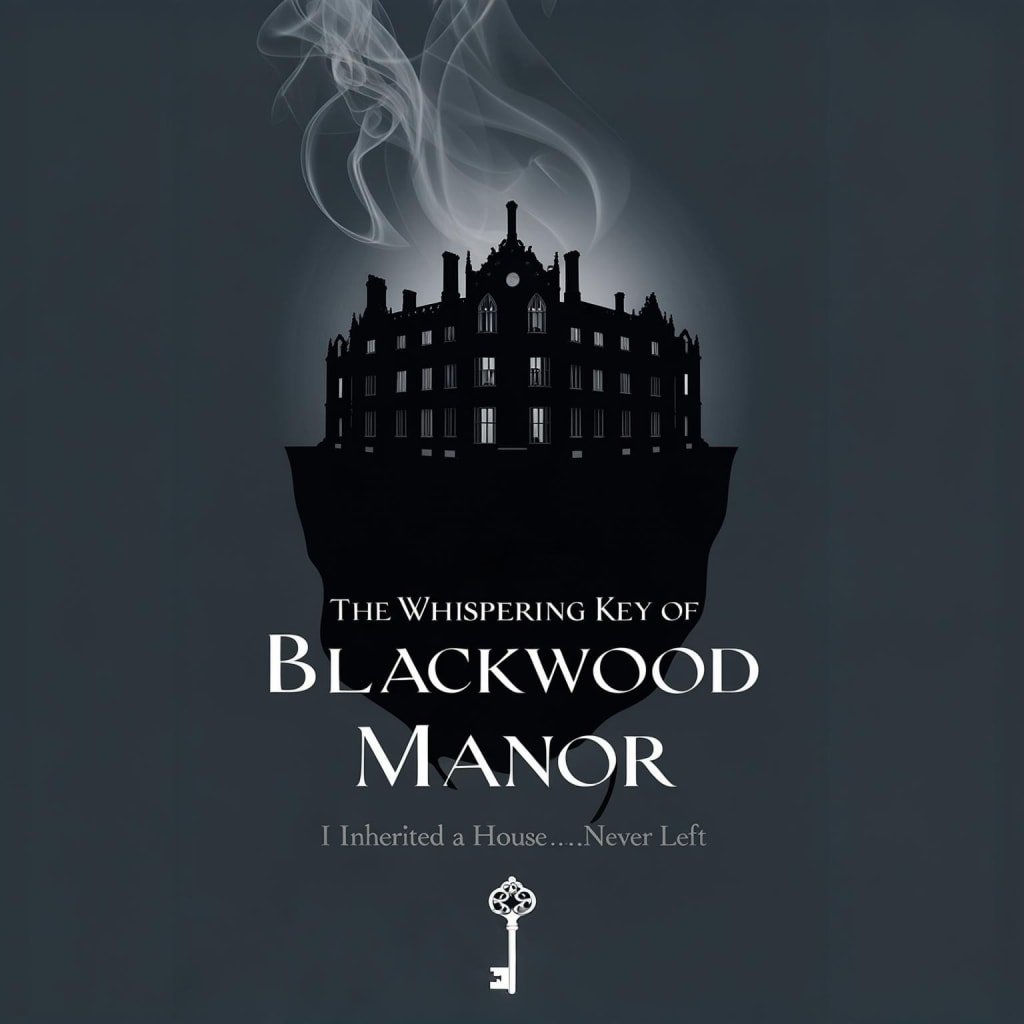

The Whispering Key of Blackwood Manor

I Inherited a House with a Locked Room—And the Diary Inside Says I Never Left

The telegram had an old-fashioned feel, with thick cream paper and black ink that ran through it. It was the sort of thing I would have found amusing if it had been delivered today. It conveyed in three sentences that my great-aunt Helena had passed away and had left Blackwood Manor to me. The envelope was secured with a key, an old-fashioned iron piece tied up with black thread. According to the courier, the house had been waiting....

I had seen pictures of Blackwood before: gables and chimneys running down the front, a driveway littered with untrimmed hedges, an old porch that creaked like rotten fruit. It sat on a hill and looked down on the town below, and over half of the stories told about it were from earlier times. The expectation was for dust, mothballs and a welcome that had the aroma of lemon oil and old tea. The locked room was unexpected.

The front door was pushed open, and I was taken by the house upon entering. The foyer was a shadowy cathedral, with imposing steps that curled up like thorns. Portraits watched from the paneled walls — stern eyes in oil and bronze — as if the family that had lived here was still deciding whether my arrival was a mistake.

“The solicitor stated that everything I saw was mine,” I had already signed the papers. He looked as if he’d been to such dwellings on multiple occasions, unsurprised. He pulled out a glossy photograph of a heavy oak door with dark iron straps. “Except the room at the rear of the east wing. It’s sealed. It always has been. There’s a key, but it hasn’t been used in decades.”

I placed the small iron key on the mantel and slept in a mixture of excitement and terror that night. Old houses do that: they hum like the inside of a throat. Upon waking at two in the morning, I heard the key slip from the mantel and fall onto the rug, as if someone were clearing their throat.

The key was warm. I picked it up; something in me — curiosity, or an inheritance older than my own name — tugged. I wrapped it in my palm and walked toward the east wing.

The corridor smelled of beeswax and lavender. The door at the end was heavier than I anticipated, a plank of oak with iron like ribs. I set the key in the lock. It resisted, then turned with a whisper that sounded like paper sliding across a table.

The door opened onto a small room no larger than a study. It was arranged with the care of a person who expects to leave and return. A desk sat beneath a tall window, curtains cut with a careful hand. Shelves lined the walls, full of books that had not been picked up in what might have been centuries. An armchair angled toward the fireplace, a blanket folded on its arm. On the desk, a leather-bound diary lay waiting, as though someone had closed it moments before and set it down.

My hands trembled. The diary’s cover was stamped with the Blackwood crest — a twisted tree — and a name that made my breath hitch: Helena.

I opened it.

The first line was my own handwriting.

I never left.

It was not written in a wobbling script of grief. It was deliberate, as if someone had been sitting at that desk with the pen for years. Page after page contained sentences like those, each one eerily intimate and impossibly present.

I respond to the kettle’s singing at four; I answer it with the old teapot.

He arrives at night and calls the house “mine” with a laugh he thinks he disguises.

I watch him from the stair, feel his shoes scuff the third step.

I stood in the room and listened for footsteps that were not coming. The diary’s pages warmed under my fingers. The entries moved from small details to things that tugged at my stomach like a hook.

He turned the key tonight.

He found the room and the diary. He reads these lines with all the belief of someone who thinks he discovers a secret. He will not believe what comes next.

The diary knew me. It knew the key. As I read, it knew the exact angle of my shoulders. I shut the book and laughed at myself — a sound full of something halfway between bravado and fright. I left the room and closed the door, the key heavy in my pocket like a secret heartbeat.

I spent a few days at Blackwood, treating it like an odd inheritance. I cataloged the books, neglected the gardens, and made tea in the old teapot Helena had favored. I found Helena’s letters in a drawer — sensible, precise notes about bills and a doctor and a plumber who never came — and nothing that explained a diary that wrote us both before anything happened.

Then I began to notice other things. There were no flowers in sight, but the west window smelled of jasmine. A faint lullaby wound along the banister and dissolved when I reached its source. Once, standing by the portrait of my grandfather, I felt a hand ghost the small of my back. There were practical oddities too: the clock in the hallway wound itself at dusk, and the tap trickled silver water at midday even when the supply had been shut.

I tried to be rational. I left the diary closed for a week. I told myself I could not read the entries and change what they announced. I believed I was the sort of person who would not be fooled by theatre.

Then, late on a rain-brushed night, I found an entry that had not been there before.

He will try to ignore me. He will think the diary is a trick. Tomorrow he will lock the room again and tell himself the past is a thing to close away. But the house remembers her promises, and the key does not forgive tricks.

I closed the diary and hid it beneath the floorboard by the hearth — the place children hide money in stories. I sat with my back to the fire and considered leaving. The rational choice would have been to sell the Manor, pocket the inheritance, and walk back into a life with work and noise and no whispering keys.

Instead, at dawn, I took the iron key and locked the door. I told myself I had humbled curiosity; I told myself the house had its secrets and I would respect them. That night the diary lay open on my chest.

He never left, it said. He thought locking it would stop me. He does not understand the difference between closing a door and closing a story.

I woke to rain and to the sense of being watched. The house had been quiet until then. Now the floorboards on the second landing breathed as if someone paced, the sweep of a skirt against the banister. I looked in the hall mirror and saw that where my reflection should have been there was also a faint, pearly outline — like a person mirrored from another pane.

Helena stood behind me in the glass. She looked younger than the photographs and older than anyone I had ever met. Her eyes were not accusing; they were simply attentive, cataloguing the small, human oddities that made life live.

“I am not trapped,” she said without moving her lips. The voice was in the room and down the corridor at once. “I never was. But stories are greedy. They like to be read.”

I thought of leaving again. I thought of trains, city lights, people who did not keep diaries that wrote them before they moved. But there was also something else: a thread of responsibility I had not expected. Blackwood had found me because we were kin in more ways than blood. It needed someone who would listen.

That afternoon I opened the diary and read aloud.

He reads me now. He will greet the garden in spring because the diary told him to plant the lavender, and when the lavender grows the bees will remember how to come back.

I planted lavender in the east border. The bees clustered and came back, buzzing like a chorus. The house softened.

As the days went on, the diary continued its slow, uncanny narration. It told me things I had not yet done and then slipped the memory of them into my life as a surprise. Once it mentioned a knock at the study window and a visiting neighbor with a dog, and when the knock came I was prepared to brew tea. Another entry warned me of a rotten stair board and I avoided the step the day my foot would have gone through.

I learned to live with the diary as one learns to live with a portrait that smiles just a shade too knowingly. It asked me questions by omission, and sometimes I answered by choice. It never demanded. Helena had written as if preserving a life inside a house was a craft, and her sentences were stitches.

Then came an entry that changed the tone.

I have said my name aloud to the house enough times to make it an echo. There is a place where stories do not need readers. He will find it if he listens. He must decide whether to stay, and, if he stays, whether the story will be only his or both of ours.

I closed the book and felt the weight of the key in my pocket. I understood, finally, that the diary’s declaration — I never left — had not been a trap or a riddle. It was an invitation. Helena had never left because she had made a pact not with time but with attention. The house kept her because she kept the house. It was mutual caretaking.

I could leave Blackwood and return it to dust and rumor, or I could stay and be part of its continuing sentences. I thought of the lavender, of the way the bees returned like punctuation. I thought of the lullaby that sometimes changed its tune to match my moods. I thought of portraits that softened when I smiled.

At dusk I took the key to the locked room and set it on the desk. I did not lock the door. I sat and wrote in the diary for the first time, slow and certain, my pen scratching into the leather like a measured breath.

I am here. I am staying. I will learn how to tell a house what it needs and how to be told what I need in return.

Outside, Blackwood’s chimneys sent up slender threads of smoke. Inside, the house agreed, with the small, steady noises of settling wood. The diary’s last line that night said, simply:

Then we will not be alone.

The whispering key rested on the desk between us, a small iron promise.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.