The Little Black Book

(Found among the papers of the late William Charles Burton, of Superior)

“Wearied with the commonplaces of a prosaic world, where even the joys of romance and adventure soon grow stale. . . [We] followed enthusiastically every aesthetic and intellectual movement which promised respite from our devastating ennui. The enigmas of the Symbolists and the ecstasies of the Pre-Raphaelites all were ours in their time, but each new mood was drained too soon of its diverting novelty and appeal. Only the sombre philosophy of the Decadents could hold us, and this we found potent only by increasing gradually the depth and diabolism of our penetrations.”

- H. P. Lovecraft, The Hound.

I am not in the least what people would consider “superstitious” or have any background in the realm of the macabre, but one thing is for certain: I am indeed cursed. A sailor married to his imperiled vessel who’s doomed to the seas of the infinite blackness for the remaining eons. Abandoned and damned at his own will; not for the absence of longing for life and all of its beauties and adventures, but due to the carnal nature of what he knows. His burden, my burden, alone to bear. But now, through the years of my excruciating self-censorship, I have finally found within me the courage to divulge that carnal knowledge, and have developed the cunning to finally end this toiling nightmare! As I pen this accursed document I must strip myself bare of all safeguards and unlearn the very disciplines I betrothed that curbed the overwhelming urge that would, indeed, bring the impending nightmare to life. This urge, one that I do not confront lightly, is to proclaim it from the highest mountaintop, propagate it from the most prestigious podiums of authority; every person has the right to know what I do! But if they did, it would only mean doom to all who heard.

You may accuse me of hubris and melodrama, or embellishing my predicaments to garner attention or, at worst, pity. Maybe even tarnish my good name and write me off as a mad man whose ravings are procured from a deep sense of existential dread of loneliness and projections of self-grander. You would not be accusing me of anything I haven’t already accused myself of many times before; if only those were the true causes of my plight. Maybe then I could finally rest, but I am afraid this tale is far removed from what can be diagnosed by any psychologist or identified by theosophist the world over. To end my jottings of eccentrism I besiege you, dear reader, to heed my warnings before continuing to peruse this document; for you, too, will be subjected to the horrors I have experienced these lonely years, and the responsibility to keep the Earth from a fatefully gruesome end will be yours alone.

My Great-Grandfather, William Claye Burton of Boston, was a well-known entrepreneur and inventor who owned and operated nearly all of the ports surrounding lakes Superior, Michigan, and Erie. After exiting the slave trade he ran a tidy and functional operation, bringing a host of varying goods imported from all across the globe; of which he himself would inspect and have full discretion over as to distribution and sale. A monopoly of this extent would rightfully be considered dubious to any governing body by modern standards, but when he began the company in 1832 he was practically the only source of imports within the midwest, after besting the remaining competition. He did this by providing the region with incredible goods from strange places that no other company could not produce, mainly because his manifests never documented the locations his ships would dock or accounted for what currency was used in his transactions. Strangely, even at achieving vast success, it was always a struggle to keep his ships and docks manned due to regular mass disappearances of his employees, and resorting to buying out and emptying local prisons to run his massive fleet. They, too, would all vanish in time. Eventually, even with the goodwill of the municipal powers set to benefit, his operation was regulated to just Superior alone, when as of 1883, his company amassed ninety-two percent of the market share among the Great Lakes. Normally this advent would come as a setback to most venture capitalists, but my Grandfather saw this regulation as an opportunity for other means for revenue. He then began acquiring real estate in storefronts along the shorelines, marketing to boutique shop owners and bohemian eclectics to sell his peculiar inventions here instead of abroad. The nature of these goods are nearly as extraordinary as they were unnerving; ranging from devices and machines that perform mundane tasks from automating food storage and preservation or aiding in heavy lifting, to luxury items that could cleanse garments or even manage whole estates. The most common of these devices took the form of vaguely humanoid automatons, each standing nearly one meter high, that would move about on their own freely and respond to nearly any command the customer could think of. These automatons would vary in composition and quality, lower-level models made from wood and bronze and high-end products being cast of a peculiar, un-characterized metal that left consumers baffled at its sheer beauty and its impressive durability. There were other products too, from decorative furniture to intriguingly complex transportation vehicles that left all who beheld them bewildered and the masses zealously eager to buy.

William Claye Burton lived a surprisingly long and healthy life, due to a combination of his odd automatons and various other inventions, he out-lived his two sons. The first son, Gregor Clancy Burton, died in infancy in 1814, second being my grandfather, Thomas Burton, whose birth in 1821 took his mother’s life in child labor and whose death in 1877 was the result of an unfortunate though suspicious accident on the docks. As his family matured, he grew tired and faded from executive involvement in the company and became weary of the incessant bickering from his unscrupulous descendants. In 1909, during a board meeting where every Burton was present, there spread an unruly fire that proved unsurvivable to all within the property and took nearly the entire night for the authorities to vanquish. I was then twelve and William Claye was watching over me from his home. We were all who remained of the Burton household. Thereafter he was present through most of my young adult life, though, on the eve of my twenty-eighth birthday he passed away at age one-hundred-two; leaving me the entirety of his wealth and capital.

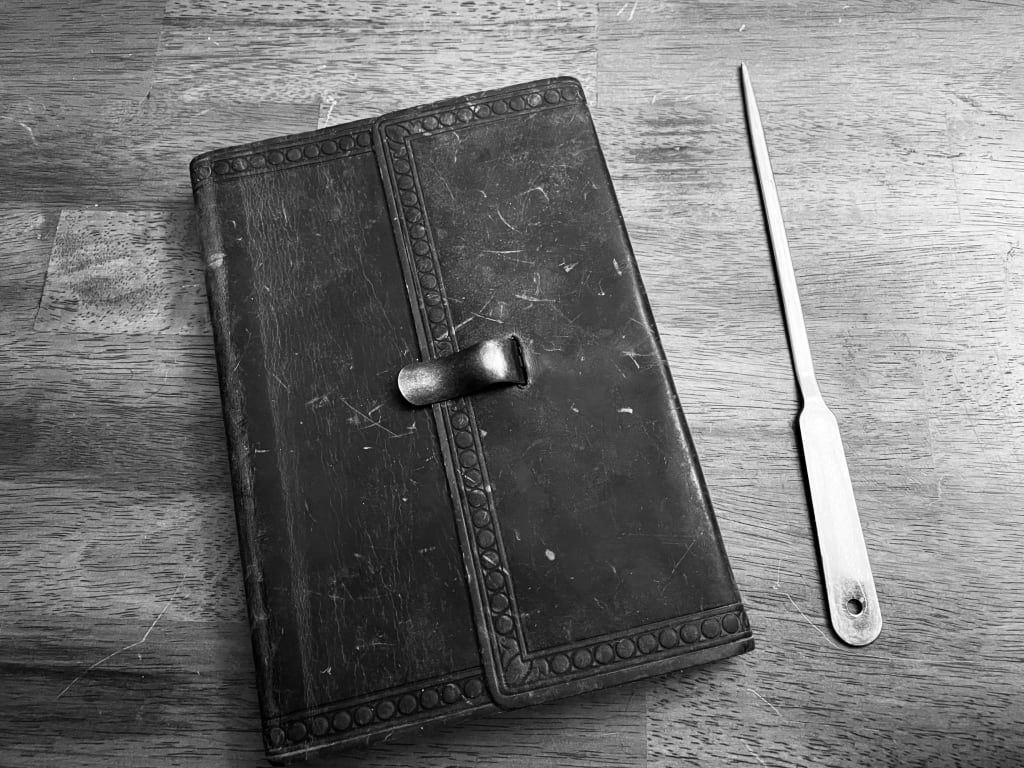

Among these effects was a large black mahogany box addressed to me with a document enshrining me the sole heir of the empire, along with a collection of small specimens of his early dormant automatons; each clutching something small in their tiny rusted hands. Public figures and politicians acted quickly to sequester the fateful package, but my Grandfather’s attorneys were tenacious and swift in securing all legal avenues to ensure my reception of the box and its contents. After the funeral procession and activities open to the commonwealth had concluded, I adjourned to my grandfather’s estate in Duluth and reviewed my bequeathal in his study. Upon opening the box I was astonished to find nearly $20,000 in antiquated notes, which is more cash I would ever assume be left liquid considering their age. It also contained a little black book, presumably some sort of diary, and a handwritten note sealed in a wax-sealed envelope bearing the family crest. The diary contained some casual notes for to-do’s and shopping lists, but nearing the end I encountered script that was diabolically formed; written in a language that I, despite my comprehensive and rigorous education, could not identify. The characters were largely comprised of varying forms of swirls and lines of differing lengths and pitches, almost resembling something child delinquents would scribble on the desks in Primary. I was immediately alarmed by these findings, as my Great-Grandfather was never the type of man who trifled with trivial games or puzzles, as he saw them as a squander of precious and immeasurably valuable time. I opened the envelope to find a message that only contained a strange sequence of numbers that read: 501.260. For a long while I was utterly perplexed by my situation: the fate of the entire company relied on me deciphering my Grandfather’s random scribbles with a string of numbers as my only tool…I had to be free of this responsibility for a short time, so I helped myself to some well-aged bourbon that he had in his desk drawer, and I let the influence of alcohol overtake me.

Casually drifting off into half-drunken memories of the times I spent with my Great-Grandfather, mainly being rebuked for my childish behavior while out in public and arduous lectures on the man of stature and class I was to become when I finally came of age, I became cognizant of a key, fateful moment. One of those memories was of a day I spent with him in the study, he chuckled at my gob-smacked face when I beheld the vast number of books he kept in there, and how he was able to keep track of them all. That’s when I remembered: he used the Dewey Decimal System to sort his massive library! I snapped out of my stupor and frantically tracked the location written down in the note, only to recoil in horror at the discovery of the dreaded volume that lie there in wait for me. It was none other than the Book of Eibon, that ghastly grimoire of untold horrors, ancient civilizations of dream-like vistas, and old spells of incomparable perversity. This, all in the Latin Liber Ivonis Edition no less! As I removed the aged text from its wretched resting place I noticed it was bookmarked. Reluctantly turning to the indicated page I shuttered at the appearance of a cipher containing the same symbols jotted in my Great-Grandfather’s diary. I knew then that William Claye did not intuit his great inventions, but relinquished them from forbidden powers that should never be allowed in the hands of any man! The decision to commence decrypting the abhorrent message was one of indebtedness to the one who raised me and whose legacy I must preserve. It took me nearly a week to break - day and night - and by the time I finished I nearly fainted ill at the message I was finally able to receive:

“No man can conceive the majesty of Hyperborea - no man hath lay a single stone of great Hyperborea. Nor beheld its metals. Nor its monoliths. It is greater than what man can build, greater than where any man may dwell. Yet. Entrance may be granted to thee. Seek audience from the Crawling Chaos that stands await for thee. He who will grant most humble admittance, nay must first be paid of thee thy form, for no man can enter. He will then sing The Song of Old -for then you will forever lay the stones of Hyperborea. For then a man ye will be no more. ‘Crucio et Umitatio Aeternum’”.

There was only a moment of confusion, then the rush of forbidden enlightenment invaded my mind and consumed my very soul! For my involuntary utterance of the words “Crucio et Umitatio Aeternum” revealed to me the carnal knowledge that has tortured me endlessly and has rendered me banished to the deepest ends of the cosmos in recompense! No sooner had I spoken The Song of Old when one of the small automata had risen to life revealing in it’s grasp a scroll bearing my father’s name. There it posed, awaiting mindlessly to grant his son’s command.

About the Creator

Jonathan Caleb

Musician, activist, aspiring writer, husband, and anxious dipshit.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.