The Real Story Of Vanderberg

Cold War Paranormal Story

These cleared ranchlands have hosted some of the most renowned news footage.

Shoot trespassers.

The most expensive California oceanfront property is not for sale. Instead, concrete motion detectors and razor-wire-topped ten-foot barriers hide it.

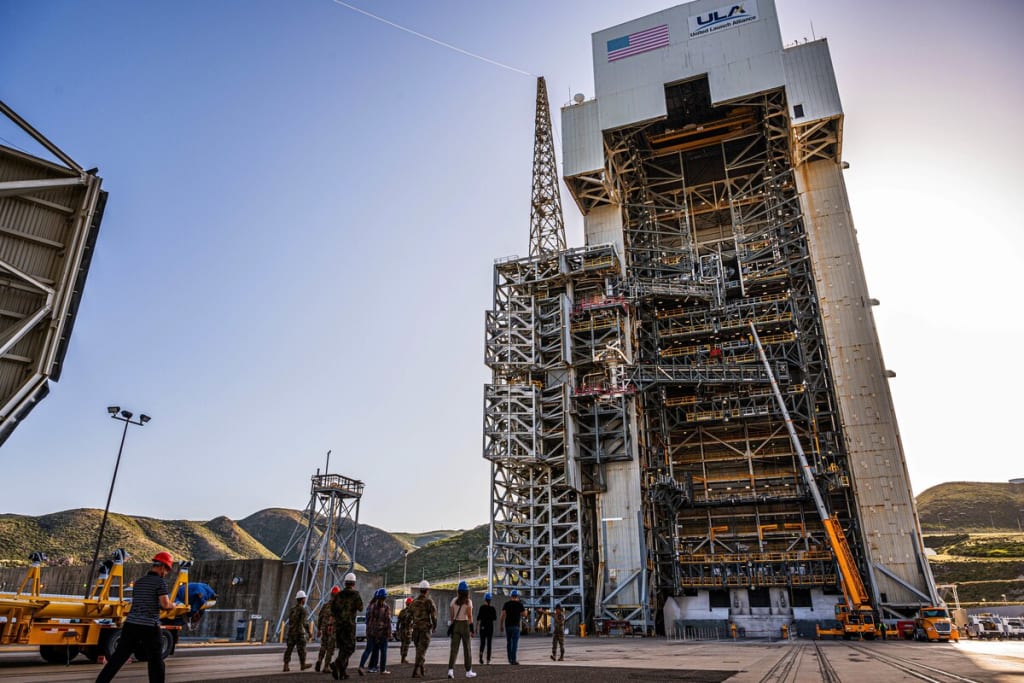

Vandenberg Air Force Base in north Santa Barbara County makes history behind closed doors. Vandenberg is the US ICBM test site. It hosts the controversial National Missile military system and launches top-secret military satellites.

Media critics called the 1980s SDI “Star Wars.” After Reagan left office, SDI seemed to expire, but President Bush revived it with the National Missile Defense system.

The arrangement allows the US flexibility in dealing with minor nuclear nations. No longer would the U.S. need its nuclear deterrence or MAD rhetoric.

The technology would allow the U.S. to retaliate to a missile launch by a lesser nuclear state without glowing the offending countries.

Four NMD tests were done. Two out of four have succeeded “if you accept the unrealistic conditions of the tests, such as placing beacons on the warhead,” said UCSB nuclear issues history of science professor Lawrence Badash.

The project's detractors include notable scientists from Berkeley, MIT, Cornell, UCLA, University of Maryland, University of Pennsylvania, and all U.S. nuclear facilities, as well as former Lockheed, Rumsfeld Commission, and Defense Science Board workers.

Others doubt rockets threaten the U.S.

CIA official testifies to Congress that non-missile delivery methods are more likely to attack U.S. territory in the future due to their lower cost and greater reliability and accuracy.

The government plans to spend $200 billion on NMD, mostly on Vandenberg. Some call the initiative a strategic vision, others a costly disaster.

Such disagreement isn't new.

Vandenberg started as Camp Cooke, a WWII tank training camp, in 1941.

Times change fast. As the Cold War peaked with ICBMs, the US focused on missiles and satellites. The government quickly discovered it could store tanks almost anywhere but test missiles only in a few areas.

Vandenberg excelled at this. Its remote location on the west coast enabled missiles and surveillance satellites to be launched into polar orbit, overlooking the Soviet Union's most important areas.

Thus, north Santa Barbara County became California's space coast. Camp Cooke gave the Air Force 64,047 of its 86,000 acres in June 1957 to create Cooke Air Force Base. The installation became Vandenberg Air Force installation in 1958. By 1960, the Air Force had purchased many south Pacific islands for target practice.

The US government began Vandenberg manned spy flights in 1966. Project name: Manned Orbiting Laboratories. MOL, code-named “Dorian,” was a surveillance space station with a capsule.

Air Force astronauts would conduct experiments and collect surveillance photos aboard the space station for a long time. After the mission, the astronauts would enter the capsule, disconnect from the station, and return to Earth.

Space Launch Complex-6 on Vandenberg houses MOL's launch facility. Engineers loved calling it Slick 6. It would become a notorious aeronautical name.

The Air Force spent billions building the massive base in north county over three years, employing hundreds.

Other technological advancements emerged alongside Slick 6. At a fraction of the expense, spy satellites may meet or surpass all MOL mission goals. When the Department of Defense canceled Project Dorian on June 10, 1969, the MOL facility was virtually finished. Abandoned Slick 6 facility.

The engineers went. Workers went. Money left.

Santa Maria, Lompoc, and Guadalupe's once-booming economy collapsed. North county almost had space-age ghost villages. Slick 6's rusted facilities were abandoned for 10 years.

The aerospace industry came up with a revolutionary space travel concept in 1972. The space shuttle was so innovative that it is still in service 30 years later with no plans to replace it.

In 1972, the U.S. chose to establish two space shuttle launch sites. These included Cape Kennedy in Florida.

The second launch site would be operated by the Air Force for top-secret military payloads. Construction would occur at Vandenberg. The Air Force told Congress in 1975 that constructing the shuttle launch complex at a huge launch site would save $100 million. Slick 6 building resumed in 1979.

Building work revealed problematic or unsustainable components of the structure. The design failed so badly that several engineers anticipated the launch complex would explode on liftoff.

Poor planning and construction plagued the facility. Eight thousand Slick welds were defective. Facility pipes were damaged or cut. Critical valves were broken or blocked.

Lack of people and severe Air Force work hours cause poor construction.

“They worked us into the ground,” recalled project engineer Marty Waldman. There was a scarcity of workers for the required tasks. Due to staffing shortages, several of us worked double shifts with no end in sight. We never knew when to sleep, wash, or anything else. Every night, weekend, and holiday was the same.”

Construction workers reported sleeping in their automobiles and working 16- and 18-hour days. Crime and divorce rose. The FBI and Air Force investigated worker drug and alcohol misuse after receiving multiple reports.

NASA estimates a one-in-100 shuttle flight mortality from Cape Kennedy. Similar calculations for Vandenberg predicted a 1 in 5 shuttle launch explosion.

One worker told Congress, “there will be only one shuttle launch from Vandenberg because the whole launch pad will collapse when it’s launched.”

The Vandenberg Public Affairs Office proclaimed Slick 6's completion early in 1985 despite launch facility issues and poor workmanship. Reagan made a similar declaration to the public in October.

Challenger detonated over Florida months before Vandenberg's first shuttle flight. As the country reeled, the Air Force secretly buried the shuttle program and disguised a $1 billion repair cost.

Each categorization of Slick 6—operational, minimum, and mothballed—made it take longer to return the facility to operating order.

Vandenberg shuttle project ended in 1989. The entire cost was $3 billion.

After another unsuccessful Air Force effort, Slick 6 was leased to Lockheed Aerospace, which had three failure launches before its first successful flight.

All these instances have created a basic legend.

The Chumash burial place was found in 1966 when clearing the slick for the MOL. Native American tribal members urged that the holy place be examined and recorded and their bones reburied somewhere.

Roger Guillemette, a Vandenberg historian, said the Air Force, insistent about its timetable, seemed to let workers complete building without hindrance. The Chumash were upset, and local folklore says a tribal chief cursed the location, causing 30 years of failed efforts.

Lockheed launched the first successful launch from Slick 6 on September 24, 1999—two years ago Monday. Slick 6's curse seems lifted.

Lockheed allegedly bribed a Chumash priest to remove it.

Reference

https://dailynexus.com/2001-09-25/this-is-rocket-science-the-stories-behind-vandenberg/

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.