The Real Haunted Story Of Demon Core

Cold War Paranormal Story

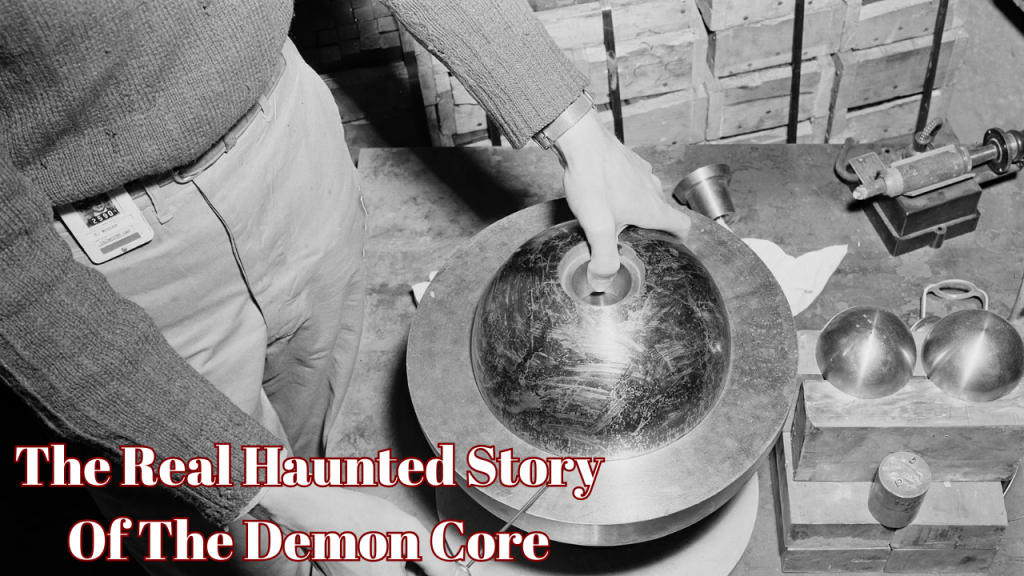

The demonstration began on the afternoon of May 21, 1946, at a secret laboratory in a canyon three miles from Los Alamos, New Mexico, the atom bomb's birthplace. Canadian scientist Louis Slotin was teaching his colleagues how to “tickling the dragon’s tail”—bringing the exposed core of a nuclear weapon to criticality. The core, lying alone on a low table, was a dull metal hemisphere with a plutonium nub in the middle, warm to the touch due to radiation. After the bombing of Nagasaki, it was quickly shaped to attack Japan again, but it was later repurposed. Slotin was likely the world's leading plutonium handler at the time. He helped manufacture the first atomic bomb a year earlier, and a contemporaneous picture shows him calmly standing near its parts with his shirt undone and sunglasses on. Back then, bombs were handcrafted.

The Slotin method was straightforward. He brought the tamper, a half-shell of beryllium, over the core, halting just before it fit tightly. The tamper would deflect neutrons from the plutonium, creating a weak, short-lived nuclear chain reaction that the scientists could observe. Left-handed Slotin held the tamper. He had a long screwdriver in his right hand to wedge between the components and keep them apart. One of his coworkers, Raemer Schreiber, was distracted by unrelated work while he slowly lowered the tamper, anticipating the experiment to remain boring until many more seconds. He heard Slotin's screwdriver slip and the tamper fall over the core behind him. After turning around, Schreiber saw a burst of blue light and felt heat on his face.

A guard guarding the plutonium in the room had little idea what Slotin was doing. After the core began glowing and people yelled, he raced out the door and up a neighboring hill. Subsequent estimations placed the total number of fission processes at roughly three quadrillion—a million times smaller than the first atomic bombs, but still enough to throw off a considerable burst of radiation. Radioactivity energized air electrons, which generated high-energy photons—the blue flash—when they returned to their unexcited form.

The lab was primarily evacuated by ambulance. While waiting for aid, the scientists calculated their radiation exposure. Slotin created a drawing of where everyone had been standing when the slide happened. He next attempted to use a radiation detector on several things that were near the core—a bristle brush, an empty Coca-Cola bottle, a hammer, a measuring tape. It was hard to acquire an accurate result since the detector was badly polluted. Slotin asked one of his colleagues to put radioactivity-detecting film badges around the area, which forced the scientist to venture dangerously near to the still hot core. A subsequent investigation noted that humans “are in no condition for rational behavior” after such an exposure, despite the mission yielding no valuable data.

The protest witnesses were hospitalized at Los Alamos. Before being examined, Slotin vomited once, then numerous times in the following hours, but stopped by dawn. His health appeared fine. But his left hand, first numb and tingling, hurt worse. This was the hand closest to the core, and scientists calculated it got about 15,000 rem of low-energy X-rays. Slotin’s whole-body dose was around twenty-one hundred rem of neutrons, gamma rays, and X rays. (Five hundred rem is usually fatal for humans.) Blisters and waxy blue skin developed on the hand. Slotin's doctors iced it to reduce swelling and agony. His right hand, which held the screwdriver, exhibited milder sensations.

Slotin phoned his parents, in Winnipeg, who were flown down to New Mexico on the Army’s pay. They came four days after the catastrophe. On the sixth day, Slotin’s white-blood-cell count decreased drastically. His pulse and temperature changed. “From this day on, the patient failed rapidly,” the study said. Slotin lost weight due to nausea and gastrointestinal discomfort. One doctor described his internal radiation burns a “three-dimensional sunburn.” On day seven, he had “mental confusion.” He was in an oxygen tent with bluish lips. He fell into a coma. Nine days after the tragedy, he died at 35. Radiation sickness, or acute radiation syndrome, was the cause. He was buried in Winnipeg in a sealed Army coffin.

Slotin was one of only two persons to die from radiation exposure at Los Alamos while the facility was under military administration. In those early years, from 1943 to 1946, there were around two dozen more deaths—truck and tractor accidents, unintended weapons discharges, a suicide, a drowning, a fall from a horse. Four deaths were due to bad luck, involving janitors who shared antifreeze-laced muscatel wine. Only Slotin and Harry Daghlian, Jr. died from Manhattan Project hazards. Daghlian performed a criticality experiment with the identical plutonium core nine months before Slotin's disaster, using tungsten-carbide blocks instead of the beryllium tamper. After dropping a block, the core temporarily turned critical. It took nearly a month to kill Daghlian.

Los Alamos stopped criticality work after Slotin's failed demonstration. It was always dangerous—Enrico Fermi informed Slotin he would be “dead within a year” if he continued—but the Second World War prioritized expediency above safety. Handcrafted critical masses were easily adjusted. By the time Slotin died, speed was unnecessary. Despite its concerns, the Cold War may be handled more slowly. After the mishap, a document advised using remote controls and “more liberal use of the inverse-square law”—the idea that a little distance reduces radiation exposure.

After the accidents, Rufus, the plutonium pit that murdered Daghlian and Slotin, became the demon core. No such derogatory names were given to the Hiroshima and Nagasaki pits that killed tens of thousands. Such is the difference, perhaps, between intended and unintended harm, between the core carefully assembled for the purpose of mass destruction and the core reserved for the realm of experiment.

References

https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/demon-core-the-strange-death-of-louis-slotin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demon_core

https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/science-technology/dr-louis-slotin-and-the-invisible-killer

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.