The Protest That Wasn’t: How Early 80s Horror Movies Turned Outrage Into Advertising

IMDb claims Eyes of a Stranger drew real protests, but did it? A dive into horror marketing, moral panic, and how outrage became the best publicity stunt of the 1980s.

They Tried to Ban It! (Or So the Poster Said)

It’s a line horror fans know by heart: “The movie they tried to stop.”

In the early 1980s, it seemed every horror movie promised that someone, somewhere, was outraged about it. If protesters weren’t real, they’d be invented. If bans didn’t happen, distributors whispered that they almost did. Outrage wasn’t bad for business — it was the business.

Take the 1981 slasher Eyes of a Stranger. IMDb trivia insists there were “actual protests outside theaters” when the film opened — a grim little thriller about voyeurism and violence starring Lauren Tewes and Jennifer Jason Leigh. It’s an intriguing claim. Except… there’s no record of those protests anywhere. No trade articles, no newspaper clippings, no reports in Variety or The Hollywood Reporter. Not even a stray mention in Florida papers, where it premiered.

That absence tells a bigger story: in the early 1980s, the myth of protest was sometimes as valuable as protest itself.

Moral Panic as Marketing Plan

Horror entered the 1980s on a blood-slicked high. Halloween (1978) had made independent horror look like a gold mine, Friday the 13th (1980) proved lightning could strike twice, and soon every studio wanted its own teenage body count.

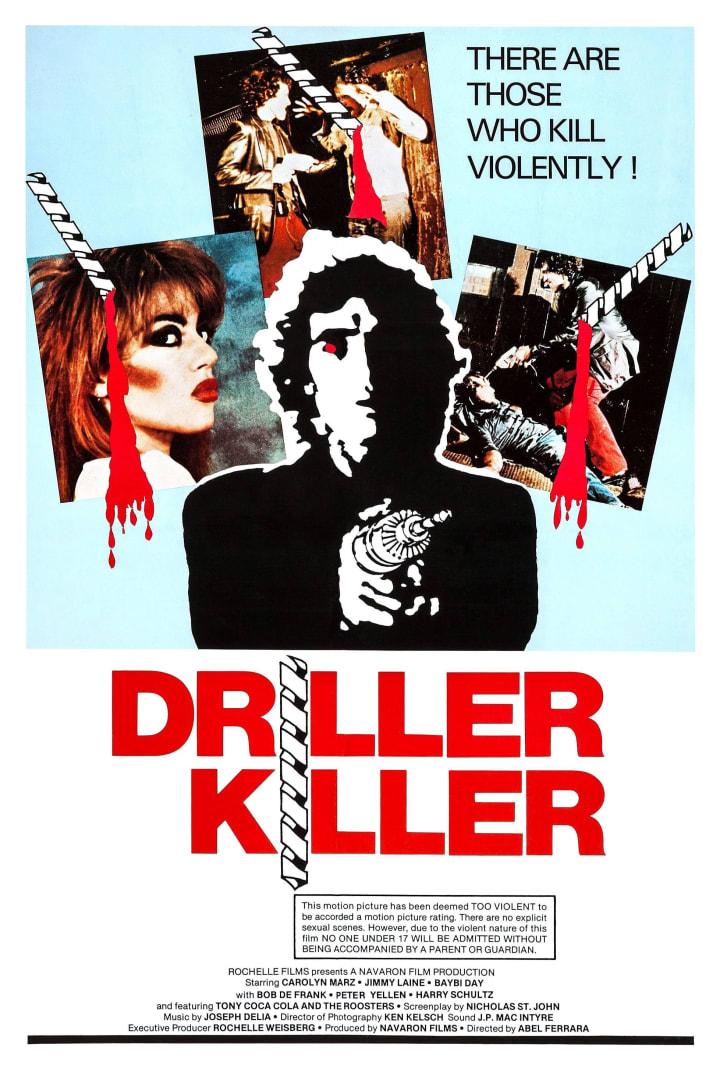

But the genre’s boom coincided with a cultural backlash. Parents’ groups, religious conservatives, and tabloid moralists warned of a “new pornography of violence.” In the U.K., campaigner Mary Whitehouse led the crusade against the so-called Video Nasties — low-budget horror tapes accused of warping young minds. British police actually raided video shops and seized copies of films like The Driller Killer and Cannibal Holocaust.

Across the Atlantic, American outrage was less organized but just as noisy. Some drive-ins quietly dropped films after community pressure; others advertised that fact as a selling point. The paradox of the early 80s horror cycle is that censorship and commerce were intertwined — the louder the outrage, the better the turnout.

Outrage as Advertising

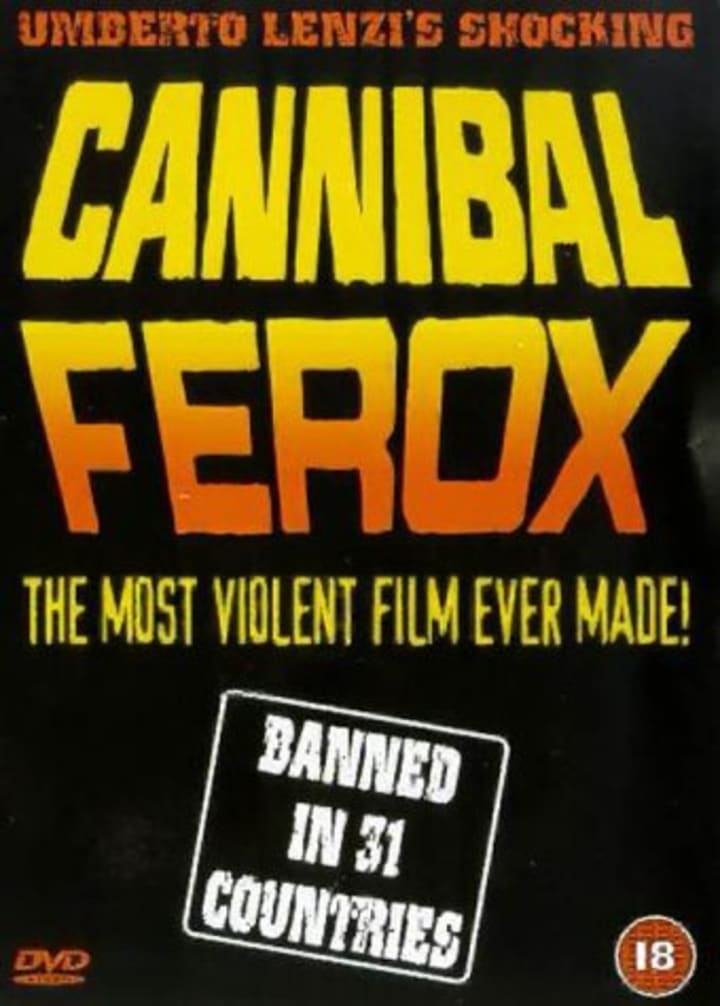

Horror marketers understood that moral panic sold tickets. Posters screamed “Banned in 31 Countries!” or “See the movie they don’t want you to see!” — whether or not anyone had actually banned anything.

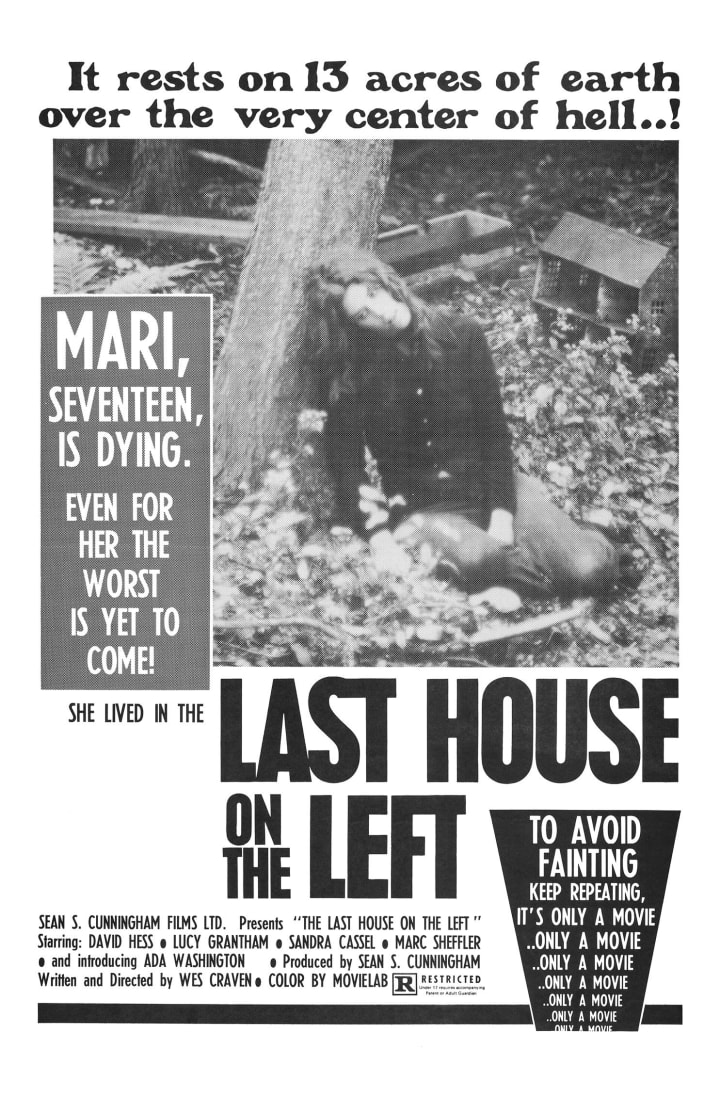

The Last House on the Left (1972) set the standard years earlier with the tagline: “To avoid fainting, keep repeating: it’s only a movie…” That line was pure theater — an invitation to experience transgression safely. By 1981, this strategy was baked into every slasher campaign.

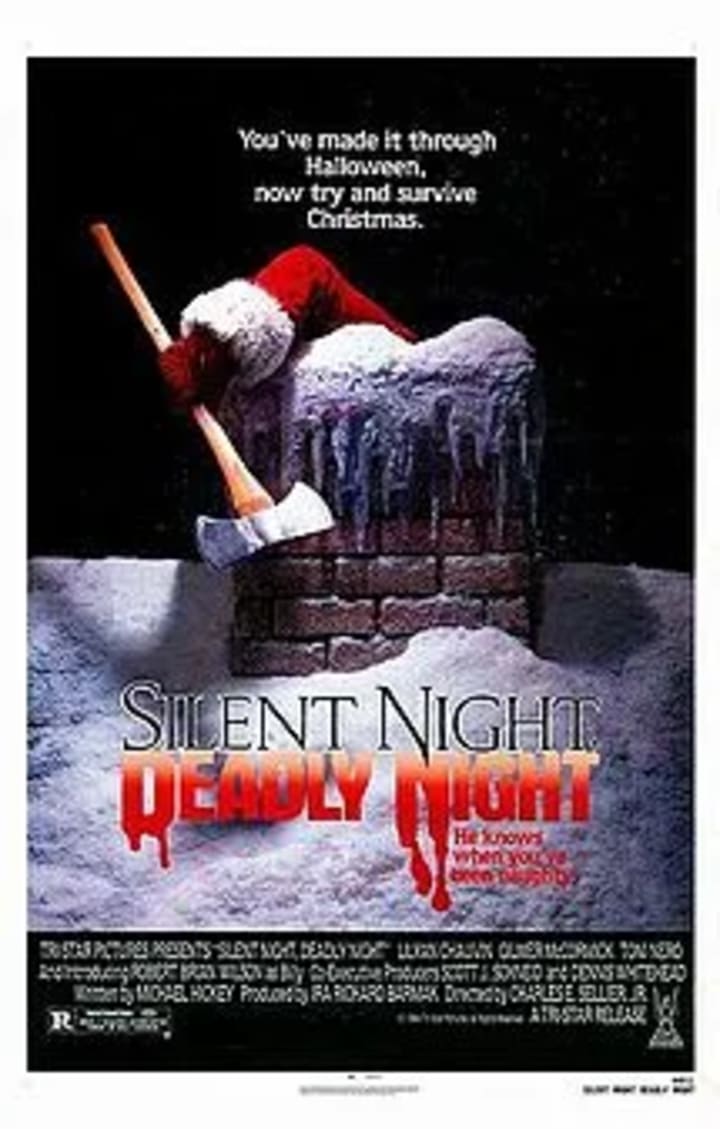

Sometimes the outrage was real. Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984) provoked legitimate picket lines led by angry parents furious about a killer Santa Claus. TriStar pulled the movie after two weeks — then quietly re-released it years later, using the controversy in its own ads.

Other times, it was smoke and mirrors. Films like I Spit on Your Grave and Cannibal Ferox courted feminist backlash and censorship threats, then used those criticisms in promotional copy. The message was clear: this film is too much for polite society.

So when a movie like Eyes of a Stranger pops up with unverifiable “protest” trivia, it fits the pattern perfectly. The rumor of outrage was its own kind of PR — a free boost from the culture wars of the time.

The Myth That Made Horror Money

It’s easy to laugh now at those breathless headlines about “video depravity.” But the panic worked — for both sides. Activists got airtime; filmmakers got ticket sales. Everyone benefited from pretending horror was dangerous.

And it was effective. When The Evil Dead (1981) was banned in parts of the U.K., the ban itself made it legendary. When Maniac (1980) was condemned for misogyny, that condemnation guaranteed it a cult audience. The push and pull between outrage and attraction became the engine of horror’s economy.

Eyes of a Stranger may not have inspired real picket signs, but it didn’t need to. Just being believed to have done so put it in the same conversation as the banned and the damned. It’s the horror equivalent of tabloid alchemy — turning moral panic into marketing gold.

Fact, Myth, and the Pleasure of the Forbidden

When we revisit this era — the fog of gore and grindhouse cinema, the tabloid sermons, the police raids over VHS tapes — we’re really seeing a battle over cultural permission. What are we allowed to see? Who decides what’s obscene?

For every banned title, there was a filmmaker who quietly smiled and watched their box office grow. For every fabricated protest story, there was an audience ready to believe it. The myth of moral outrage gave horror a strange legitimacy. It wasn’t just blood anymore; it was rebellion.

Closing Credits: Why It Still Matters

The early 80s horror backlash wasn’t just a cultural scuffle — it was a marketing revolution. It proved that the line between censorship and publicity could vanish entirely.

Today, streaming services still play the same game. “Too disturbing for Netflix.” “Banned TikTok trailer.” “Viewers can’t finish it.” It’s all the same formula, born in the grindhouses of 1981.

Maybe Eyes of a Stranger never had protesters at all. But the idea that it could have — that horror was dangerous, transgressive, powerful enough to offend — that’s what sold the ticket.

And in that way, the myth is the most truthful thing about it.

Subscribe to Movies of the 80s here on Vocal and on YouTube for more 80s Movie Nostalgia.

About the Creator

Movies of the 80s

We love the 1980s. Everything on this page is all about movies of the 1980s. Starting in 1980 and working our way the decade, we are preserving the stories and movies of the greatest decade, the 80s. https://www.youtube.com/@Moviesofthe80s

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.