The following account was found in a box of diaries purchased in a London auction house in 1977. While its validity remains questionable, certain records suggest that events similar to those described did occur in Punjab Province in February, 1905.

...I did not know wealth as a young man. My father had a weak constitution and died of cholera shortly after my twentieth year. With what money I had earned and what little he had left me I bought passage to India. I had been told that a man could make his fortune there, and I was a fool then for I believed it. For a few years I wandered through the North, working any job I could, and like this I narrowly scraped by.

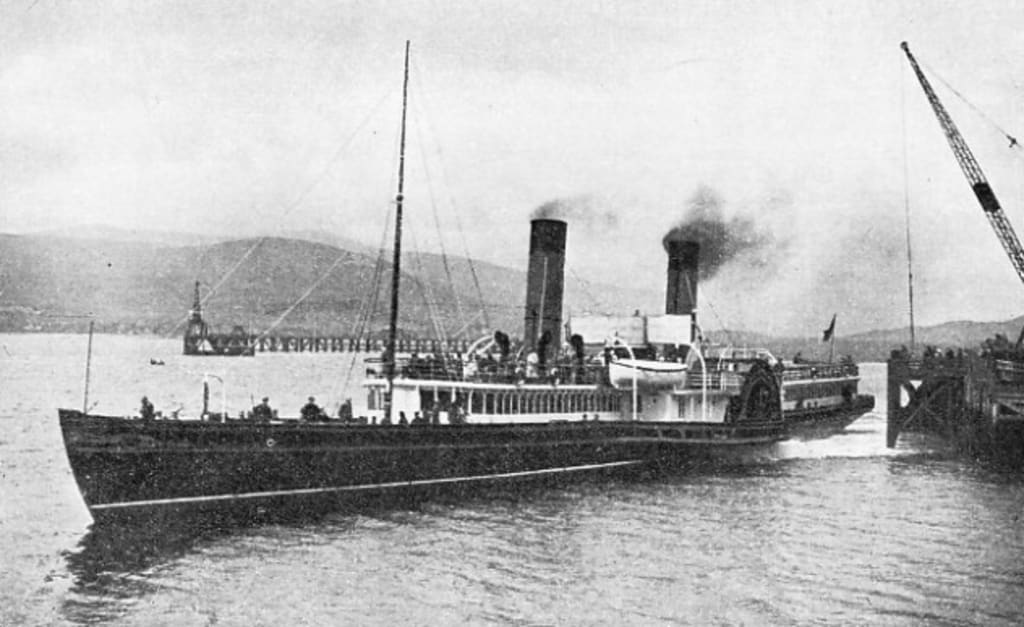

Finally, in 1881, I found myself a position on a steamboat which ran supplies and guns to the outposts of the North-West Frontier. It was only one job to begin with, but the captain offered to keep me on, and I was willing, for the pay was good. Two jobs turned to three, three to four and so on. What had begun as a temporary occupation turned into my profession, and for more than two decades I worked up the Indus River.

Throughout those years I saw many strange sights and met a great number of peculiar people and I reckon I could tell a thousand tales from those days. However, none rattled me so much as the incident at Pala-Kani. I can only describe the entire episode and its circumstances as bizarre, and while it troubles me to admit it, nothing more than that singular event facilitated my retirement from the river service.

It was in February of 1905, and had started as a routine supply trip. By then I was the second officer aboard the steamboat Ursula, crewed by ten and commanded by Captain Müller, an ageing Austrian widely known to be a martinet. We left Hyderabad at the beginning of the year and travelled five hundred miles up river to arrive in Nandla a month later.

The way there was easy enough. We were not beset by any problems and everyone aboard was cheerful as could be. After arriving in Nandla, our ship was joined by a single passenger, a young lieutenant who had become bored with frontier life and was headed back to England after resigning his commission. After a day the haulers had unloaded the supplies at the outpost, and soon we were ready for the return journey.

We were away quickly, and all seemed well. The dry season never causes much bother on the river, and we were glad of the rest. Normally we would have stopped a few days for standard repairs; however, Müller’s efficiency was unmatched, and he insisted that we get back to Hyderabad for the next assignment as soon as possible. The overworked engine seized after two weeks headed downriver, and we were forced to stop for onboard repairs.

So it was that on an afternoon in late February, we docked at a small village nestled in an oxbow. The youngest of our crew, a Multan lad who had some knowledge of the area, told us it was called Pala-Kani. The landscape of the region was desolate and barren, but within three miles on either side of the river, swathes of dense brush and forest crept out into the watercourse. Pala-Kani stood as a little dusty outcrop amongst an untouched sea of green.

While Müller ordered the engineer to assess the damage, I was sent for fresh water and food from the village, and to have a telegram sent to the shipping office in Hyderabad alerting them of our delayed arrival. I took Daniel Thomas, the stoker, and Atma, the Multan boy, for I did not know the language. We were also joined by the young lieutenant, who was eager to stretch his legs after his long period of stagnation.

However, as soon as we had drawn up along the banks, something struck me as odd. So many of the other sleepy villages along the meandering Indus had grown used to the river traffic, and therefore gave little attention to visitors. The only ones to ever take notice were the children, who lazily watched us from the banks and sometimes waved and laughed or threw rocks as far as they could. However, Pala-Kani greeted us in numbers. All of us flocked to the sides to see dozens of villagers, arms raised, shouting for us to come down.

Most of the men thought that this was some practice of hospitality, and were eager to disembark. Müller, however, who disapproved of congregating with the natives, ordered all to stay aboard. Only we four descended, and as we did so, the locals seemed to be gathering about the young lieutenant. Being of seniority, I had Atma translate the questions of the loudest village representative, a slender old man.

“Where have you come from? How many are you?” he began.

“We are from Nandla heading to Hyderabad, we are here to purchase food and water.”

“Are there soldiers with you?”

“No, we are not a military vessel. Can we buy supplies here?”

“You help us and we will give you water.”

“Help you with what?”

“There is danger in the forest.”

Bandits were nothing new in the North. Afghan warlords have always seen it as their right to range across the frontier, raiding as they go, and I have known many hamlets and villages ransacked in the night, with groaning wounded and weeping children left behind to starve. I turned to Thomas, who had been in the river service nearly as long as myself.

“Danny, how many arms do we carry?”

“We have the five rifles, but as you know Jack they’re rusted something awful,” he replied.

“That they are Danny. Still, might do to try and scare off the blighters.”

“Depends on how many of them there are,” interjected the young lieutenant, who had been listening intently to all the goings on.

I nodded to Atma, and he gave the question to the old man. Atma listened and furrowed his brow. As he thought on the elder’s words I could tell he was having trouble figuring out a translation.

“I think sir, that it is not a human danger. He says it is a beast.”

“A tiger no doubt,” said the lieutenant.

“Ah well,” said Thomas, “I reckon a few flares should see it off.”

“And how many flares do we have Danny?” I asked.

“Ten or so signal flares, they burn dreadful crimson at night.”

“Grand, then we’ll scare it off tonight. Tell them we’ll help them this evening Atma, in the meanwhile we’ll have our food and water.”

Atma told the elder, but he and the rest of the crowd, who had been largely silent during our exchange, seemed to find this unsatisfactory, and they spent some time chattering amongst themselves. Eventually the old man spoke up.

“He says,” Atma translated, “That they would rather have us help them now during the day, he says it is dangerous at night, he says it comes at night.”

“Tell him we have guns.”

“He says it makes no difference.”

“We’ll see,” I scoffed, although in honesty I was becoming nervous, “Then tell him that we’ll have to see what we can do.”

With that, we returned to the ship. Müller was barking orders down to the engineer, who was still deciding on the best course of repair. I joined the captain on the quarterdeck and explained that a tiger in the forest was causing trouble, and that if we killed it, the villagers would grant us all the food and water we’d need. Upon reporting the situation, he grew unusually contemplative.

“Tigers eh?” he finally said, “I do not think it wise to go near the forest. Tell them that we’ll pay in cash for the supplies.”

“I don’t think they want the money Captain Müller, they seem to be more worried about the beast.

“Well then we will have to do without Mr. Daventry.”

“Very well sir, but seeing as it wouldn’t do any harm, might the lieutenant, Mr. Thomas, Atma and myself take the rifles and scout around the village? Just to put their minds at ease.”

“Seeing as there is nothing to be done aboard at present, I will allow it. But I warn you Mr. Daventry, no good ever came of chasing after tigers. You must return by evening.”

“Aye sir.”

I descended and yelled for Atma to fetch the rifles from below. I joined Thomas and the lieutenant on the bow.

“So what’s the plan Jack?” asked Thomas.

“We’ll look around a bit. Not much else we can do.”

“What about the beast? The tiger! We can’t pass up a hunt,” said the lieutenant.

“Müller’s orders. Besides, I haven’t a clue about hunting, let alone tigers.”

Here the lieutenant became very excited, and began to recount stories about his uncle's big game hunts in Africa, and how the same uncle had been employed in shooting lions which terrorised railway workers in Kenya. He even got out a ring to show to us, he told us his uncle had taken it from one of the victims as a kind of memento. He seemed to have got it into his head that he was on an adventure, and ran off to his cabin to get his own hunting rifle.

“He’s got no patience that one,” Thomas remarked as Atma handed him a rifle.

“That he doesn’t Danny,” I said as I slung mine over my shoulder.

Once we were all ready, we came down the gangplank much to the relief of the elder and his villagers. We were led by the old man through the settlement and in the direction of the distant woodland. As we approached from the spindly dock we saw the bay absent of any fisherman’s dinghy or longboat, which was unusual for the hamlets of the Indus. The village itself was a meagre assortment of huts and bungalows all centred around a meeting hall.

Smoke rose from perhaps half the buildings, but even with such a large crowd it did not seem very populated. There were empty traps and nets hanging from the buildings, all of which were vacant. We were led onward through the settlement and into the fields. Except for our guide, the villagers began to disperse as we traversed further along. The wind blew over the small plain and whistled through the dry maize, which rustled all around us as we proceeded.

Beyond, we could see the forest, and the closer we got, the denser it looked. We were about halfway between the village and the forest when the old man stopped. He stood before a post, and would not take his eyes off the woods in front of him. While the rest of the fields had been harvested, the land beyond the post had evidently been abandoned, leaving a markedly barren territory.

The lieutenant looked as if he were about to continue, but the elder grabbed his arm and looked into his eyes with terror. Atma translated his warning.

“He says that the marker should not be crossed so close to the day’s end.”

“Would he have us come back tomorrow? We can’t kill the damn thing if we can’t get in the forest.”

The old man looked fraught with fear, and was nervously shifting his weight. His discomfort soon became our own. The lieutenant had taken a ring in the shape of a snake from his tunic and slipped it on his finger. It was the one from Kenya.

“Come on, the sooner we get it over with, the better,” said Danny, and he was the first forward. The lieutenant joined him, as did I. Atma looked just as frightened as the old man, and I said he could stand guard if he wished, which I think relieved him greatly.

As we went up the road, the forest seemed to loom. It was lit up beautifully with the afternoon sun behind it, and a few rays of light seemed to penetrate its canopy, but it made it seem so much more immense, so much more impenetrable than when we saw it from the Ursula as we chugged along the river. Stumps of corn lay uncollected and rotting beneath our boots, and they made an awful crunch as we stepped through them.

“That’s strange,” observed the lieutenant.

“What’s that?” I said.

“There’s another post here. And over there, another one!”

At intervals ranging from a few feet to several yards, the path bore a series of wooden posts. All of them were painted red and decorated with an assortment of plants, flowers, and small bits of animal bone.

“What do you think they mean?” I asked.

“I haven’t the foggiest.” he replied.

“It’s simple,” began Thomas, “They put one up for every victim.”

His solemn hypothesis put us all in a sombre state as we passed by the tenth or so marker.

“It must be getting bolder,” said the lieutenant.

“Or it’s realisin’,” said Thomas.

“Realising what Danny?”

“Realising they can’t do nothin’ about it.”

We said nothing more until we came to the end of the deserted fields. Small bushes and a few fig

trees had taken hold on the side of the fence that marked the beginning of the settlement, and they turned into the forest further along the path. Apart from the buzz of insects in the pasture, the forest seemed to be enveloped in an eerie silence.

“This place gives me the fear,” muttered Thomas.

“What’s the plan then?” I asked.

The lieutenant, who looked far less enthusiastic than he had an hour before, thought for a full minute before he spoke.

“I say we go up the road a ways, look for any pathways in the brush. The first thing we need to do is find the lair, then we’ll flush the bastard out.”

Thomas and I took this formulation as sufficient, and we nodded in agreement. He took the lead and we followed up behind, our rifles unslung. The path had not been travelled in some time, and roots and weeds had begun to cleave their way through the dry earth. Arms and branches of ancient hardwoods crept out above, as if they sought to reclaim the narrow strip of road.

Neither birdsong nor the monotonous chirp of insects were to be heard, only the wind far above. It had been a hot day, and the ground was caked in dust, but here, it was like entering a cellar. However, the cool air was not welcoming. My skin crawled with the sudden chill and I rolled down my shirt sleeves. Danny, who was ahead of me, was looking back and forth nervously.

“It’s not right,” said Danny.

“Quiet man! If the bugger hears us we’ll never find him!” hoarsely whispered the lieutenant.

“What couldn’t hear us here? We must be the only living things in the godforsaken place,” said Thomas.

“That’s why he’s preying on the villagers. My uncle told me about this sort of thing. It was the same in Kenya with the railway workers. When the lion runs out of beasts to hunt, he comes for man.”

He dramatically bore his hand into a fist to show the snake ring on his little finger.

“How many villagers would you say there were Jack?” asked Thomas.

“I don’t know, fifty? Maybe more,” I postulated.

“And how many huts did you count?”

“God, I don’t bloody know! I wasn’t counting them as sheep Dan.”

“Well I did, and I tell you there’s something off here. There were thirty huts or more, and I’ve known with a population of a hundred live in fewer than twenty.”

“What’s your point Danny?”

“There’s just too few of ‘em.”

Again, this somber remark turned us quiet, and for the better part of an hour we eased our way up the wood. Not once did we see any disturbance in the foliage, and no pathways that the tiger could have used appeared. In fact, the further we went, the worse it got. The silence seemed to pierce our ears, a kind of pinching hum emanated from all around. I think we all hoped the wood would run out and went, the worse it got. The silence seemed to pierce our ears, a kind of pinching hum emanated from all around. I think we all hoped the wood would run out and we would be greeted by the familiar bleak plains of Punjab, but no such luck. Through the canopy, the sky seemed darker, and it was clear that night would be on us soon.

“I say we turn back,” I said, and the others gravely nodded.

We trekked back quite carelessly, and even if we had maintained a cautious retreat, there was no chance the beast hadn’t realised our presence. I hoped that it was satisfied in our bold advance, and that it would not return to the village. However, I quickly dismissed this wishful thinking.

We emerged from the wilderness just as the sun declined behind Ursula’s funnel, and we saw the elder and Atma sitting by the distant marker. Atma stood up and waved, a cheerful sight. Although I pitied the villagers, I was glad at the prospect of getting back on the river.

“Look there Jack,” said Danny, pointing.

For the first time I saw that the small riverboats had been piled between the outermost huts, so as to create a kind of barricade.

“Poor blighters.”

We were led back, and as we passed back through Pala-Kani, the villagers had changed from a bare hope to a doleful resignation. The faces of the little ones were undoubtedly the worst. I suspected that it had begun with the children.

I asked Atma to tell the old man that we had found nothing, and that perhaps the beast was scared off by our presence alone. His response was silence.

We returned to the ship quickly, where the lieutenant found the captain and spoke with him hurriedly. I talked with the engineer, who had assessed the damage as extensive. Ursula was hardly in her prime, and the replacement parts would need to be adjusted. Having underestimated the extent of our engine troubles, Müller had withdrawn to his cabin to make preparations for the journey tomorrow morning. The prospect of being moored to that place, that cursed village, unsettled Thomas and I, and we leant over the bulwarks gazing at the forest’s edge for some time. We knew that the beast, or whatever it was, would not cease its attacks on our account.

“I have an idea,” said the excited lieutenant, who had decided to interrupt our vigil.

“Good evening,” I said.

“We’ll light the place up, get a perimeter of torches. That way we’ll be able to see it coming and kill it at a distance.”

“We’re not sharpshooters, Lieutenant,” I said.

“Well perhaps not, but I’m a decent shot from a few hundred yards. I think I could ease down close by the tall leaves, close enough to wound the beast at least.”

“Seems like a fool’s errand,” said Thomas.

“What does the captain think?”

“I’ve spoken with Müller, he seemed unconvinced but allowed us the materials.”

I looked at Danny, he said nothing. He was right, it was a fool’s errand, but I agreed that it was better than doing nothing. The lieutenant recruited Atma to find yard posts, rags and a can of paraffin oil. We helped him carry it all down to the village and into the outer fields. The villagers and their elder watched us from the barricade, tentatively whispering to one another.

The four of us spent the better part of an hour hammering in posts a few feet apart a hundred or so yards around the barricade of boats as we worked against the setting sun. The darkening day cast long shadows as we plunged the last post into the dry earth.

As the sky sank from pale red to dim purple, we wet the rags in paraffin and set the posts alight. We layed damp blankets below so as to stop the fields from catching fire, then all of us retired to the village, save the lieutenant. He scouted out a shallow mound behind which he took up his position, rifle in hand, barely a Thus began our lonely night. We had been waiting and watching no more than an hour when Thomas spoke up in his usual dismal mood.

“What are we going to do if he gets himself killed?” .

“Beats me Danny, but I don’t think he’s that much of a fool,”

“I reckon we’ll need our rifles before the night’s out,” he said dolefully.

“Very well. You go with Atma and get the three best ones, and two dozen rounds for each man, just to be sure.”

He nodded and off they went, leaving me in the company of the two villagers who hadn’t withdrawn into their huts. The lieutenant was crouching perfectly still, his rifle tilted back behind the mound, his head peeking out into the darkness. He had taken off his pith helmet and lain it by his side, where a few cartridges had been conveniently placed.

The torches flickered in the wind coming from up river, and it seemed to grow exponentially darker as the deep blue sky turned to starless black. Then I began to hear it. It started as hardly noticeable, perhaps the result of yawning a few times in a row. But I knew it wasn't that. It was that hum, that piercing hum that sent a spike into one’s head and caused a wave of blinking.

That dreadful noise, if I can rightly call it a noise, made me dip my head down and cover my ears, but even then it just kept on, like needles had been driven into my ears. I looked up to see the young lieutenant, absolutely still. Worse than that, I could sense movement beyond. The darkness seemed to shift, not like a beast moving within it, but the night itself was shifting around our solitary outpost of light, and we knew that it could, at any moment, envelope us.

The lieutenant raised his rifle and aimed it at a confluence of movement. In one swift motion he locked the bolt and pulled the trigger, and the deafening explosion sent a wave of screaming through the village. At once, every single one of the torches were extinguished. It was as if the candles had been blown out on a cake. The last thing I glimpsed in the dim light of the burning posts was the lieutenant, standing up to meet his end, rifle in hand.

I froze. The calamity of the situation dawned on me as I turned back to the ship. Distantly I could make out the silhouettes of men by the gangplank. Danny’s voice cried out for me and I ran towards the sound. Behind me I could sense it moving; the whole darkness had surrounded the village. I could have tripped at any moment, for I would have been running blind had it not been for the Ursula’s gas-lamps. I dared not look behind me, for that electric hum snapped at the hairs on my neck. Just as I was sure that it had caught me, someone let off a signal flare and the whole plain was illuminated in the horrible crimson light.

I was not as far from the ship as I had anticipated, and it wasn’t long before I reached the dock. At the gangplank I was greeted by Danny, Atma, the engineer and Captain Müller, all armed to the teeth. As I approached them I looked back. The village and its fields were desolate and devoid of any trace of the young marksman. The only thing I spotted by the lieutenant’s perch was his helmet, in the same place he had left it.

“What the Devil were you thinking!?” cried the captain.

Müller’s face burned red with unrelenting rage, but behind his fury I could sense that he had the same biting fear in his heart as the rest of us. I couldn’t think. The hum had reached its full intensity, and I thought my skull would explode if it didn’t subside.

“He told us, he told you—”

“The Lieutenant said he’d spoken to you sir, he said he’d told you his plan,” Danny interrupted.

“He did no such thing Mr. Thomas! Now come on, if we are to have any decent chance at finding him, we must start within the next hour,” Müller scornfully peered at me, “You look ill Mr. Daventry. You had best get back to quarters. Atma, take him back to the ship.”

“Aye aye, sir,” said the lad, and grasping my arm we staggered back aboard.

I did not exactly sleep through that night, for I heard so much shouting and commotion that it would have been impossible regardless. That throbbing noise would not leave despite feeble attempts to quell my agitation. But eventually, as the rest of them returned towards the dawn, I began to drift into dreamless and painful slumber.

When I awoke we had already left the village far behind. The last memory I have of it is bathed in the red light of the flares and the villagers confusedly trying to get passage on the ship.

Thomas told me they scoured the fields well into the night, and only stopped when they ran out of signal glares. They found neither hide nor hair of the young lieutenant. Atma took the helmet back, although I don’t quite know why. Müller had ordered us away as soon as the repairs were finished, and as the ship sputtered to life and pulled away down the river, Atma and Thomas looked at the tired and haggard faces of the villagers as they peered at their last hope disappear behind the oxbow. Neither Danny nor Atma could count the elder’s face in amongst them.

Two weeks later we reached Hyderabad. Müller reported the incident at the magistrate’s office. It was only when we wired the news of the lieutenant’s disappearance to the Nandla outpost that we realised none of us remembered his name, although he had certainly told it to us. That was my last job on the Indus. I haven’t seen that place since, nor should I care to.

However, I’m afraid that was not the last I heard of Pala-Kani.

Dan Thomas never stopped working the rivers, as he had known no other life, but migrated south after the incident. It was only eight years later that we had a chance meeting in Kochi, where I had found work in the shipping office.

Of course, we shared a few drinks, and a few turned to many and we talked about the old days on the river, and old Captain Müller, who had apparently died two years back, and how the rest of the lads were doing. Eventually, our conversation drifted towards the end of my career, and inevitably to the subject of the Pala-Kani incident.

“They had an investigation, you know,” he said after a long silence, “The Provincial Superintendent even got Atma to lead him and his men up the river, up the very same route—just to see where the poor blighter had got to.”

“And?”

“Nothing,” he took a long swig from his glass, “Nothing. They went in one side of the oxbow and came out the other without any break in the trees...it was like,” Danny paused, and he shifted in his seat, his eyebrows lowered, “It was like there had never been a village there at all.”

There was another long silence before I spoke.

“Did you ever find out his name?”

“Oh, someone told it to me but I’ve forgotten Jack. I shouldn’t like to remember it anyhow,” he took another long gulp, “Müller told me after that the tribunal ruled the death an act of God.”

“The death? It a disappearance, wasn't it?”

He shook his head, and looked me in the eye.

“It was a full year after. A full bloody year. A hand washed up in Nandla. It had that ring Jack. On the little finger. Remember? That Kenyan ring?”

“I remember Danny.”

I could picture it now, the ring in the shape of a snake. Thomas filled his glass and downed it at once.

“One of his old chums identified it. Christ above, Jack—it was as if it were sliced off that very day, clean as a knife through butter.”

He shook his head again.

“Do you ever wonder Jack? About what was in that forest? There weren’t nothing good in it. Nothing at all. I can’t help thinking of it. It’s the same feeling you get, on those dark nights, you know? Do you remember how dark it was? Couldn’t see your own nose in front of you. It was a miracle it didn’t get the lot of us. I think it could’ve, mind you. No, it were toying with us. It won out in the end. There weren’t nothing we could do. Nothing at all,” he stopped, deep in contemplation, “Anyway, that was the last I heard of it.”

I solemnly nodded, and we finished our drinks. We talked a little more about the changing times, the river service, and the state of the Raj, but soon we parted ways. It wasn’t long after our chance meeting that I left India. That was twelve years ago now, and I haven’t seen Dan Thomas since...

About the Creator

Charles Lamb

I mainly write historical fiction horror short stories, mainly in an epistolary style. If this kind of thing appeals to you, give something of mine a read!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.