“Bernadette Wilkes?”

Bunny rose to her feet and nodded. A disembodied voice beckoned her from the other side of a door reading Algernon Saxton-Hughes, Esq. in gold script.

The door was solid, heavy, but the hinges were well oiled. It didn’t squeak when Bunny opened it, as she had expected, and closed just as silently behind her. She found herself within the confines of quite possibly the world’s oldest attorney. The smell was the the first thing to hit her, something between parchment, leather, and tobacco. Not entirely unpleasant, she thought. Even a little comforting, considering the unusual circumstances.

Installed at a gargantuan mahogany desk, surrounded by endless stacks of paper was the man behind the title. He rose slightly to extend a crepe paper hand, revealing a cartoonishly rotund belly, stuffed into a bespoke suit like a sausage. Bunny took it politely and he gave her one solid pump. He spoke, a cigar clenched between rows of stained teeth, “Please have a seat, Miss Wilkes.”

“You can call me Bunny.”

A phlegmy laugh erupted, “Well, okay, Bunny. Then you can call me Al.” He rocked back into his chair, its springs whining in protest. “I’m sure you’re wondering why you’re here.”

—

Bunny never imagined

having any family, as an only child of a single mother, an artist, who passed after a lifetime of untreated mental illness, Bunny had been on her own since she was a teenager. With no one to rely on but herself, every opportunity was conjured from pure necessity. Bunny managed to carve out a tiny piece of heaven, after a decade of working during the day at any crappy job that would take her, and writing at night. She wrote what she knew, what she saw, the people she encountered, and posted it. Again and again. It’s all she could think to do to survive. Miraculously, people began reading, then more, and by the eve of her 25th year, Bunny had enough subscribers to be able to quit the other jobs. Because, a real life magazine wanted to hire her, to write.

It came as some surprise on her first day of work to receive a call not about her upcoming assignment, but in regards to an inheritance, from a long lost relative, to be bestowed once Bunny turned 25.

—

She remained perched

on a tufted chair in this strange little office, on her birthday, as her lunch hour dwindled. Bunny stared at Al, waiting for him to explain. His head was a speckled egg, topped with a cloud of candy floss.

“Were you aware of your great aunt’s final will and testament?”

Bunny shrugged. “I wasn’t aware she existed.”

More wet chuckling. “Well, she’s apparently your namesake. Bernadette Chloe Wilkes.”

“Chloe was my mother’s name. She never mentioned an aunt.” Or anyone else, she thought. Much of her childhood was murky. Her information was gleaned from a few faded photographs and the journals she kept as a girl. Memories re-learned. Her mind couldn’t recreate her mother’s face, only what she would call her, when lucid. Always in a sing-song

“My funny Bunny.”

“I’m assuming she never mentioned your trust, either.”

Bunny shook her head.

“She was quite the prolific painter, B.C. Wilkes. Most people didn’t know she was a woman.” Al puffed his cigar. Through a plume, “Her works amassed a sizable sum, and when you were born, a percentage of the estate was set aside.”

Bunny kept composure, her insides roiling, emotions wrestling. She had essentially nothing her entire life, let alone the knowledge of a famous aunt, and a trust fund. Why did she and her mother struggle so much, then? Was it just the illness? Acute anxiety depressive disorder. Could things have been different?

“Unfortunately, your great aunt suffered from what was called Melancholia and, well, people took advantage. Nearly all of it was spent, save for a couple scant items that appeared virtually worthless. These are what remain of your trust.”

Bunny stood, anger bubbling, mostly at herself for getting hopes up. “You can keep it, or throw it away. I didn’t know her, after all.”

Al held up a hand, grinning. “Notice I used the word appeared, when describing the value of your inheritance?” He opened a drawer, pulling out a brown paper package the size of a text book, and slid it towards her.

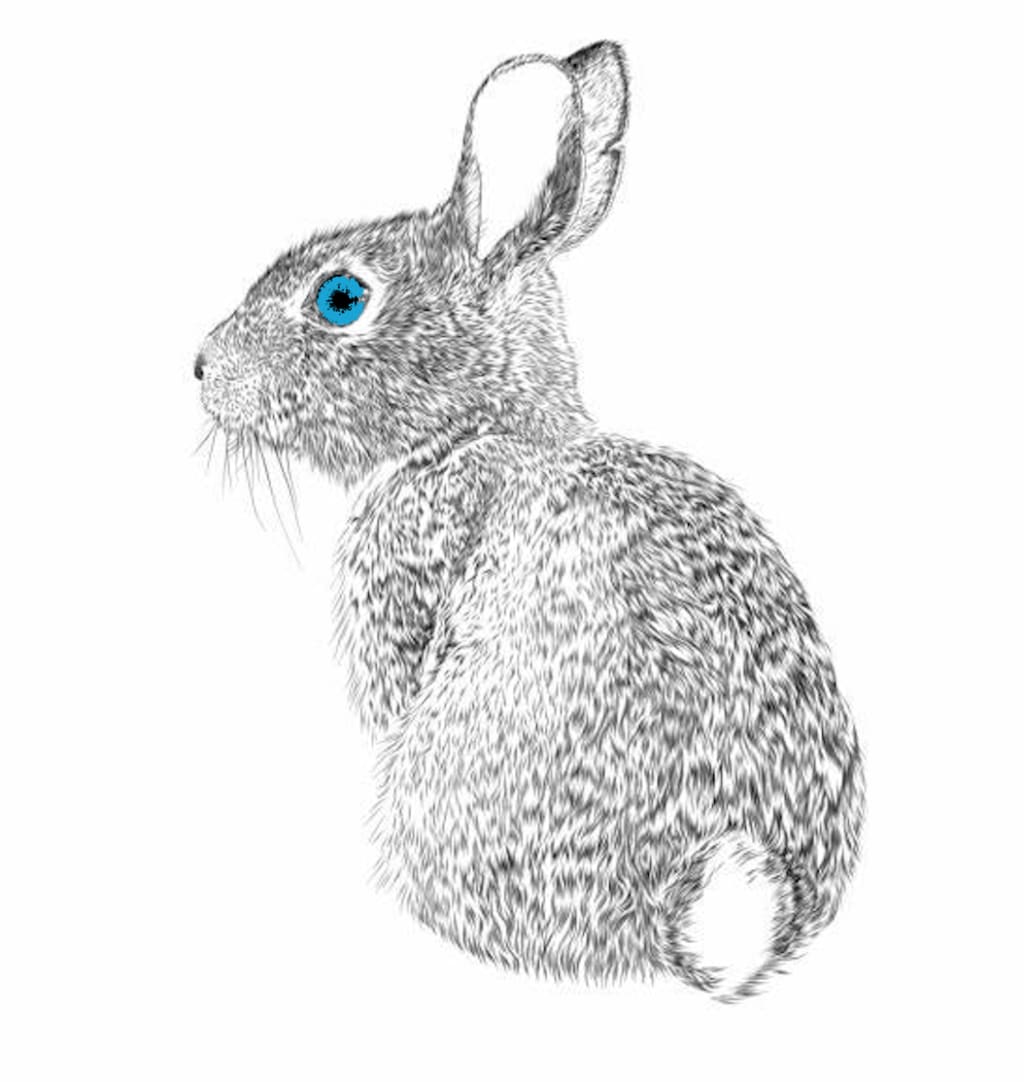

Bunny picked it up, realizing its lightness. It can’t be a book. She tore away the paper, and staring back at her was... an eye. Oil on stretched canvas, brush strokes preserved in time depicted an ocean blue iris against black fur. Letters spelling B.C. Wilkes were scrawled at the bottom.

“It’s not like any of her earlier works. We thought she stopped painting decades before, when her condition worsened. This was found behind a dresser, along with the journal.”

Bunny tilted the painting, and a tiny black book fell onto the desk. She opened it, flipping pages. All were blank, except one. “I’m not certain what animal is depicted...”

“It’s a rabbit.” Bunny answered without looking up, chilled to the bone, reading a single line in slanted penmanship:

'We cannot learn without pain.'

“A quote by Aristotle, I believe. But wait, there’s more!” Al coughed another chortle, presenting a business envelope. “There were bills hidden in the pages, amounting to roughly $25,000. I’ve taken the liberty of consolidating the total.”

Bunny peeked inside. Addressed to her was more money than she’s seen in her entire life. Happy birthday to me.

“That, along with the value of the painting, should you choose to sell it, could total over $50,000. Though it’s nowhere near what the estate once was, it’s nothing to sneeze at.”

As if on cue, Bunny sneezed.

—

Bunny is back

at work, motionless in her cubicle. The events of the last hour have hijacked her momentum. The windfall should thrill her, at the very least. But, the fire in her belly has been quenched by the aqua blue of The Eye.

The Eye. It’s cold to the touch, Bunny thought as she slid the painting to the very back of her desk. She know’s that’s impossible, something her mother would’ve said. This is the most she’s thought of her mother.

She tries and fails to focus, the rest of the day lost in a blink. Bunny’s little corner at her desk is absolutely frigid. She shivers, unable to shake it off, to force that image from her mind. An instinctive alarm sounds.

If Bunny doesn’t move, she’s going to freeze to death.

—

It’s better in the library.

Insulated. She weaves through the corridors, guided by an unknown force. The stars align, and Bunny finds what she seeks. She checks out just before closing, passing a bulletin board filled with overlapping business cards, flyers, and the like.

Something’s off. Bunny examines the corner of a postcard. Patrons file out around her, letting a gust of wind into the building. It envelops Bunny, making her break out in gooseflesh. She leans in, staring at a little blue dot at the corner of an otherwise black square. The dot... is an iris.

—

The liquid feels good

going down, thawing Bunny from the inside out. She’s seated at a trendy coffee shop, with a mug between her hands. Bunny doesn’t treat herself to expensive coffee, but desperate times... Were they? She has money to her name, and her dream job, if she could just get to work. Then, why was Bunny so wound up? The sensation was all-encompassing... a greeting from the past. Unknowable fear.

Bunny stares at the book on her lap, running her fingers over embossed words that spell: ‘Occultist Art of the 20th Century’

She turns the pages, yellowed over decades of handling. Beneath her family name, a series of prints make a grid. They all come from the same pastel world. Al was right, they are decidedly different than The Eye.

Bunny notices that the subject and the theme collide. Soft lines in muted colors show repetitions in the form of pyramids and unclothed women. Goats, blossoms. The moon. Blood. Anguished expressions against a pink sky. Branches grow out of stone, horns sprout from flowing locks, blood drips from a lunar eclipse. We cannot learn without pain.

Bunny’s throat is tight. Her mother’s own artistry, sculpture, left a similar impression. A battle fought in each piece. A battle both women lost.

Bunny closes the cover and gazes out the window. The street lights have come on. A winnebago, painted black, stops at an intersection. Bunny sips the last of her coffee and nearly aspirates when the liquid in her mouth is nearly frozen. She clears her throat, putting down the cup. When she looks up again, the RV is pulling away. The spare tire on the hatch has a vibrant cover. Aquamarine, with a black pupil, boring into Bunny.

—

“Are you feeling all right?”

Bunny’s teeth chatter as she sits opposite her boss. A progress report, he called it, when he asked her to his office. Routine, he assured. He’s bespectacled, with a fatherly quality, not that Bunny would know anything about that.

Bunny bites her lip, to still the chattering. “I don’t have... enough for you to read yet.”

He waits.

“I’m fine. Everything is fine. I just, I found out... I found a better story, I think.”

“Okay?”

Her hands have begun to tremble. “I found out I was named after my great aunt, a painter called B. C. Wilkes.”

“I’m not familiar.”

Bunny senses concern, picking up the pace. “She was apparently a major part of the occultist movement in the mid century. She was legitimately successful, too. Her pieces were in museums, in demand. Most people didn’t even know she was a woman.”

“I’m confused. What’s the angle?”

Bunny holds herself, tremors setting in. “The angle is that her paintings held power.”

“Come again?”

Words pour out, rapid-fire. “I mean, people thought her paintings held power, because of her spiritual practices. And she died under mysterious circumstances. Melancholia. I think it’s related. It’s in a book I found at the library.

Bunny paces now. Her boss holds up a hand. “Bunny, this sounds... intriguing. However, a task was put in your hands, with a very real printing deadline. Perhaps we can shelf this?“

“No!” Bunny protests, too loudly. "She even wrote a message in a little journal. And she left me a painting. I think it’s of me! I can feel its power!” If she didn’t know better, Bunny would swear her mother was the one ranting. But, her mother is dead and she can see her own breath.

“Can someone turn on the BLOODY HEAT?!”

Her boss approaches tentatively. He takes off his glasses, leveling with her. “Bunny?”

She meets his gaze. Bushy black brows frame two blue marbles, preternatural, turning her to ice. Bunny recoils, scrambling back. “GET AWAY!”

—

Everything is beige.

The walls, the blinds, the tiles on the floor, the tiles on the ceiling, all void of color. Bunny is bundled on a daybed of sorts. She sees her mother’s face, for the first time, without having to look at a picture. At last, Bunny is warm.

There’s a knock. Bunny’s mother evaporates and a shaggy dog of a man appears. He, too, wears beige. “How are you, Bernadette?”

Bunny doesn’t correct him.

“I know we’ve gone over your family history, and the more recent developments. Change can be jarring, sometimes exposing unaddressed trauma. I want you to know, there’s support here. It feels scary now, but you can emerge victorious! In the meantime...”

He reaches into a briefcase, retrieving the little black notebook. “I thought you could keep writing.”

Bunny opens it, running a finger over the single handwritten line. Moisture has crystalized on the page, forming a snowflake pattern.

“And a little piece of home?” He places something over the journal.

Lightning shoots through Bunny, splintering into a million tiny icicles.

The Eye. Bunny screams.

About the Creator

Lauren Storm

Say yes.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.