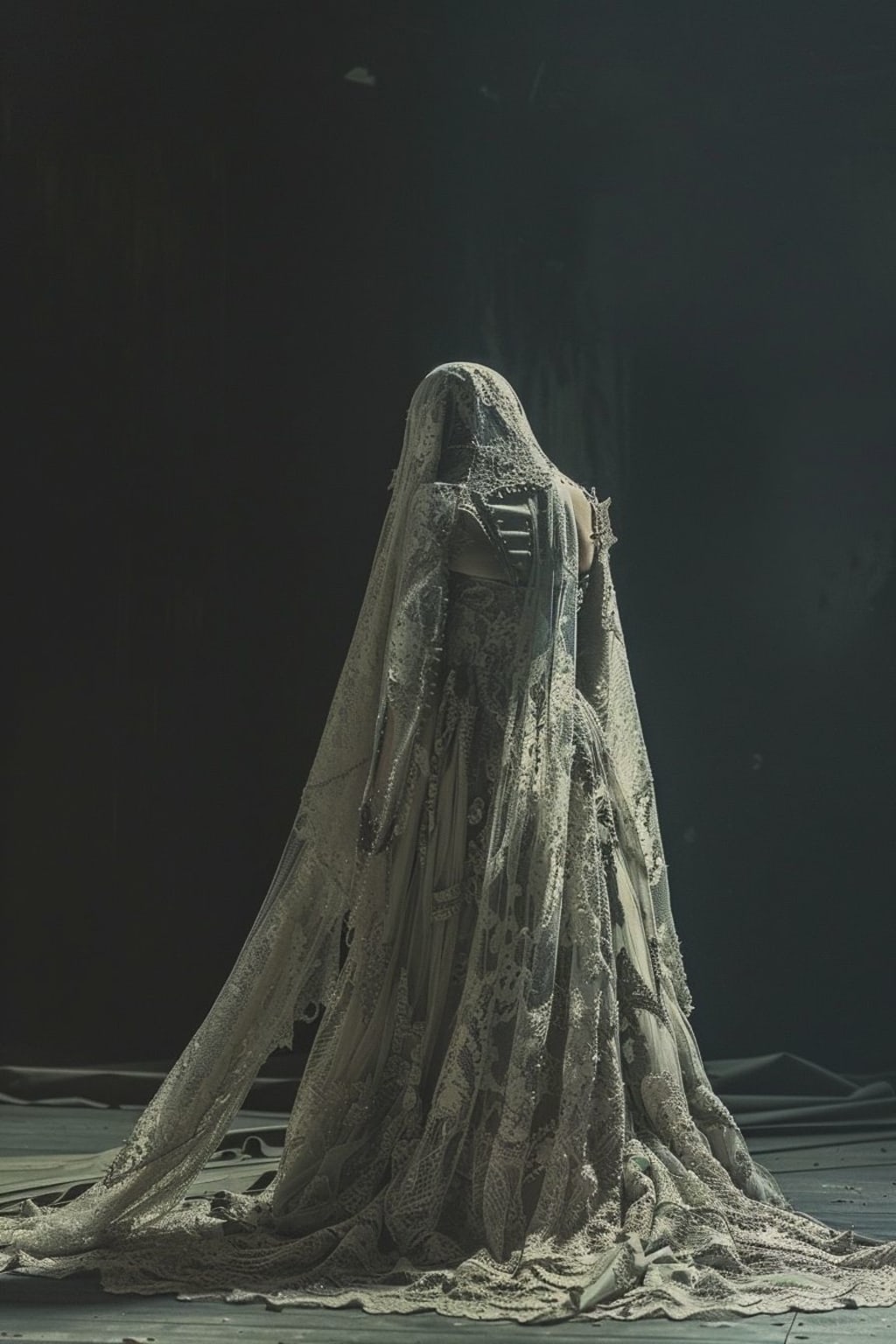

The Brides in Fairy Tales Were Never the Happy Ones

An investigation into why folklore treats marriage as a death sentence

I've been researching fairy tale brides for three months, and I need to tell you something that nobody wants to hear:

In folklore, the wedding is rarely the happy ending.

It's the beginning of the horror.

The Pattern

Start with Bluebeard.

The tale exists in dozens of cultures under different names, but the structure is always the same: A wealthy man marries a young woman. He gives her a key and one rule. She breaks the rule and discovers the bodies of his previous wives.

In some versions, she escapes. In others, she doesn't.

But here's what every version agrees on: the moment she became a bride, she entered a contract that gave him access to murder.

The wedding wasn't the ending. It was the trap closing.

Now look at "The Robber Bridegroom."

A young woman is betrothed to a man she's never met. Before the wedding, she visits his house in the forest. She hides and watches as he and his gang murder a girl and eat her. At the wedding feast, the bride tells this story as if it were a dream. The robber laughs—until she produces the dead girl's finger as proof.

The tale is explicit: marriage to a stranger is marriage to a potential murderer.

The vows are made. The contract signed. The woman's family gets their alliance or their money. And the bride gets a locked room she's not supposed to open.

What the Research Shows

I spoke to Dr. Maria Tatar at Harvard, who studies the evolution of fairy tales. She told me something I couldn't stop thinking about:

"The happy ending—the wedding, the 'happily ever after'—that's the Victorian addition. In the original oral traditions collected by the Grimms, the wedding was often where the real story began. Marriage wasn't aspirational. It was transactional. And the bride was the transaction."

Look at the numbers:

In the original 1812 Grimm collection, over 40% of tales involving marriage show it as dangerous, confining, or deadly for women.

Brides who vanish before their weddings.

Brides murdered on their wedding nights.

Brides who discover their husbands are monsters, devils, or corpses.

Brides who must solve impossible riddles to avoid execution.

Brides who are traded like property between men.

The Victorian era scrubbed most of this out. By the time Disney got hold of the stories, marriage had become the prize—the thing the princess earned through beauty, silence, and compliance.

But the old tales remembered what the new ones tried to erase: marriage, for women, was often a form of burial.

The River Brides

Here's a pattern that appears across cultures:

A woman walks into a river wearing her wedding dress.

Sometimes it's the night before her wedding. Sometimes it's the night of. Sometimes it's years into a marriage she never wanted.

But the image is consistent: white dress, moving water, disappearance.

In Serbian folklore, there's a tale of a bride who throws herself into the Danube rather than marry the man her father chose. The river takes her, and from then on, other brides who walk too close to the water report hearing her singing—not in sorrow, but in relief.

In Japanese folklore, the tale of the bride who becomes a river spirit after drowning herself to escape an arranged marriage. She's not a vengeful ghost. She's a guardian who helps other women escape.

In Mexican-American border folklore, La Llorona's origin story—before it became a morality tale about bad mothers—was often about a woman who drowned herself to escape a violent husband. Her weeping wasn't grief. It was rage that the river couldn't contain.

The river, across cultures, represents the same thing: the only exit from a contract you never consented to.

The Burning Brides

Then there are the brides who burn.

Not metaphorically. Literally.

In Indian folklore, the practice of sati—widow self-immolation—was sometimes framed as voluntary devotion. But the tales told by women to women revealed the truth: the pyre was built for her whether she chose it or not.

In European folklore, there's a recurring image: the bride whose veil catches fire from the candles at her own wedding. In some versions, it's an accident. In others, it's unclear. The bride burns, and the tale asks: was it the candle's fault, or did she lean into the flame?

Medieval storytellers understood something modern ones forgot: fire is both destruction and purification. The burning bride is both victim and agent.

She burns the life she was given. Even if she burns with it.

The Mechanical Brides

There's a subset of tales—less well-known—about brides who become automata.

In one 17th-century German tale, a clockmaker builds a perfect mechanical bride for a prince. She never argues. Never ages. Never disobeys. The prince is delighted until he discovers she has no heart—literally. Just gears where her chest should be.

He demands the clockmaker fix this. The clockmaker says: "You wanted a bride who would never defy you. This is what that looks like."

The tale was a satire, originally. A critique of men who wanted wives without wills.

But women who heard it understood something else: they were already the mechanical bride. Already performing perfect compliance. Already winding the key that kept the system running.

The only difference was, their gears were made of obligation instead of metal.

The Bone Brides

The darkest tales are the ones where the bride becomes skeletal.

There's a Russian folktale about a woman who marries a man who claims to love her "forever." Every year, she grows thinner. More translucent. Until finally, she's nothing but bones in a wedding dress, still dancing at his command.

The tale was told as a warning: devotion that demands everything will take everything.

In Celtic folklore, there are stories of brides who waste away from grief or duty until they're nothing but bone and veil. Their husbands insist they're still beautiful. Still wives. Still bound by vows.

The horror isn't the transformation. It's that no one acknowledges it's happening.

What the Vows Actually Meant

Here's what I learned researching historical marriage vows:

The traditional phrase "till death do us part" wasn't romantic.

It was a property contract.

Women, in most of Western history, became legal property of their husbands upon marriage. Their bodies, their earnings, their children—transferred ownership. The vow wasn't a promise of love.

It was a transfer deed.

And folklore remembered this.

The tales about brides weren't about romance gone wrong. They were about women recognizing the cage only after it locked.

The river bride who walks into water isn't mentally ill. She's making a rational choice about which death she prefers.

The burning bride isn't a cautionary tale about candles. She's burning the contract itself.

The bone bride isn't wasting away from love. She's being consumed by a system that calls consumption "devotion."

Why We Forgot

The sanitization of fairy tales coincided with the Romanticization of marriage.

By the Victorian era, women were being told that marriage was their highest calling. Their natural destiny. The source of all happiness and meaning.

Tales that suggested otherwise had to be revised.

Brides who escaped became brides who were rescued.

Brides who resisted became brides who learned to submit.

Brides who chose death became cautionary tales about mental instability.

The river bride became "the girl who was too emotional."

The burning bride became "the girl who was careless."

The bone bride became "the girl who didn't appreciate what she had."

The tales were rewritten to blame the bride for her own entrapment.

What the Old Women Knew

I found a collection of oral tales recorded in Appalachia in the 1930s by the WPA Federal Writers' Project. One caught my attention:

An old woman telling a story about a bride who disappeared on her wedding night. When asked what happened to her, the old woman said: "She went where brides go when they can't say no out loud."

The interviewer asked: "Where's that?"

The old woman smiled. "The river. The fire. The deep woods. The places that keep secrets better than families do."

The old women knew.

Marriage, in a world where women couldn't own property, couldn't divorce, couldn't refuse—marriage was often a choice between one form of death or another.

The tales remembered this.

We just stopped listening.

Why This Matters Now

You might think this is historical. That modern marriage is different. That we've evolved beyond the property-transfer model.

But the images persist.

Brides still wear white—originally a symbol of property, not purity.

Fathers still "give away" daughters.

Women still take their husbands' names, erasing their own.

And women still write stories about brides who escape.

The tales keep surfacing because the pattern keeps recurring: systems that call themselves love but function as ownership.

Not all marriages, obviously. But enough that the folklore keeps warning us.

Enough that contemporary writers keep returning to the image of the bride as prisoner, the wedding as trap, the vow as a door that only locks from the outside.

What the Tales Were Really About

After three months of research, here's what I believe:

The bride tales weren't about weddings.

They were about autonomy and its absence.

They were about vows made in silence—by fathers, by families, by systems that treated women as negotiations rather than people.

They were about the moment you realize the life you were given isn't the life you'd choose.

And they were about what you do when escape requires transformation so complete you might not survive it.

The river bride isn't choosing death.

She's choosing the river over the vow.

The burning bride isn't careless with candles.

She's burning the dress that was never hers to wear.

The bone bride isn't wasting away from love.

She's revealing what was always underneath the performance.

The Question the Tales Keep Asking

Every bride tale I studied came back to the same question:

What do you do when the only way out is through?

Through the river.

Through the fire.

Through the transformation that might kill you.

The tales don't offer easy answers.

They just remind us: the brides were never the happy ones.

They were the ones who had to choose.

The old tales remember what we've been taught to forget.

Maybe it's time we started listening.

About the Creator

Leslie L. Stevens

Leslie L. Stevens writes short fiction and narrative essays about silence, power, and what people refuse to say. Rooted in West Texas landscapes, her work blends realism with unease and emotional precision

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.