The Acid Bath Murderer: England’s Most Chilling Conman-Turned-Killer

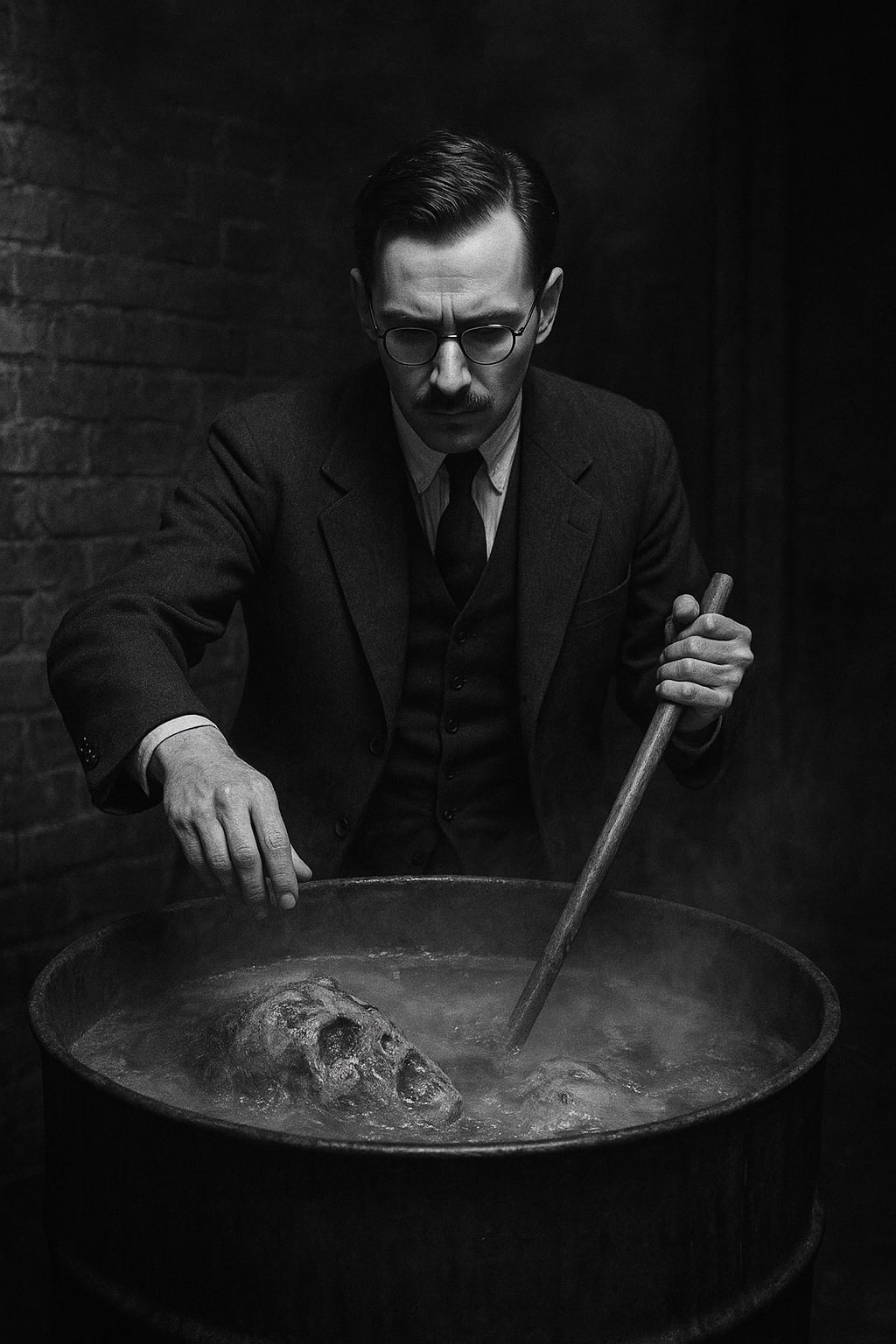

On the surface, John George Haigh was everything post-war Britain admired: polite, charming, and immaculately dressed. He moved through hotel lobbies and tearooms like a man of means, a businessman who enjoyed fine living. But beneath the polished veneer was one of the most calculating killers in British history. To Haigh, murder was not a crime of passion but a business plan — and sulfuric acid was the tool that would make him untouchable.

The press would name him the “Acid Bath Murderer,” and his trial in 1949 would horrify a nation still recovering from war.

A Strict Childhood, a Hidden Darkness

Born in 1909 in Lincolnshire to a devout Plymouth Brethren family, John George Haigh grew up in a home ruled by religious discipline and moral rigidity. Forbidden from mixing with other children, he was raised in isolation, warned constantly of sin and eternal damnation. Outwardly, he seemed a model child — gifted in music, clever in school, obedient at church.

But as he entered adulthood, the respectable mask began to slip. Haigh discovered forgery, theft, and fraud. Prison sentences followed, and each time he emerged more cunning than before. Somewhere along the way, he developed a chilling theory: if there’s no body, there can be no crime.

It was a theory he would put into practice with terrifying precision.

The First Kill

In 1944, Haigh lured William McSwan, a wealthy engineer he had once worked for, to a basement in London. There, Haigh bludgeoned him to death before placing the body into a steel drum of concentrated sulfuric acid. The gruesome experiment worked. Within hours, McSwan’s remains had reduced to sludge, which Haigh poured down a drain.

With the body gone, Haigh assumed himself safe. He took over McSwan’s possessions and finances, explaining to McSwan’s elderly parents that their son had fled abroad to avoid military service. But when the couple pressed for answers, Haigh decided they too were a liability. Both were murdered in the same way, their bodies consigned to acid.

Haigh now had not only his first victims but his first fortune.

The Hendersons and the Widow

The murders of the McSwans emboldened him. Haigh craved money, fine clothes, and status — and he was prepared to kill for them. His next targets were Dr. Archibald Henderson and his wife, Rose, a refined couple who lived comfortably in London. Haigh befriended them over music and conversation, eventually luring them to his workshop. Both were murdered and dissolved in acid, their property quickly transferred into Haigh’s control.

But greed never rests. In 1949, Haigh set his sights on Mrs. Olive Durand-Deacon, a wealthy widow living at the Onslow Court Hotel where he was staying. He invited her to see a “new invention” in his workshop. Once inside, he shot her in the back of the head and placed her body into the vat of acid.

This time, however, he had underestimated his own arrogance.

Forensics Expose the “Perfect Crime”

When Olive Durand-Deacon failed to return home, her disappearance was reported almost immediately. She was a woman of wealth and routine — unlikely to vanish without notice. Investigators quickly zeroed in on Haigh, who was known to be the last person seen with her.

A search of his workshop shattered his illusion of the perfect crime. Forensic experts sifted through the acid sludge and recovered fragments Haigh believed had been destroyed forever: human fat, a portion of a foot, gallstones, and dentures that matched Olive Durand-Deacon.

Science had defeated Haigh’s deadly logic.

The Confession

Convinced the evidence against him was insurmountable, Haigh began to talk — and once he started, he didn’t stop. He admitted to killing Olive, the Hendersons, and the McSwans. In chilling detail, he explained how he dissolved their remains in acid, reducing lives to nothing but liquid waste. He even hinted at other murders, though some claims were likely attempts to exaggerate his notoriety.

Perhaps most disturbing was his cold reasoning. “Where there is no body,” Haigh told police, “there is no crime.”

Trial and Execution

Haigh’s trial opened in July 1949 and became a media spectacle. Newspapers seized on the lurid details, branding him the “Acid Bath Murderer”. In court, Haigh’s defense argued insanity, citing supposed blood-drinking fantasies and recurring dreams. But the jury saw through the ploy. His careful planning, financial motives, and methodical disposal of bodies revealed not madness but meticulous malice.

On August 10, 1949, John George Haigh was convicted and sentenced to death. One week later, he was hanged at Wandsworth Prison.

A Legacy of Horror

The Acid Bath Murders remain one of Britain’s most macabre crimes, forever entwining Haigh’s name with terror. His arrogance, his chilling belief in a “perfect crime,” and his cold-blooded pursuit of wealth through murder turned him into one of the most infamous killers in British history.

But perhaps the most enduring legacy of the case is the reminder that even the most careful criminals leave traces behind. Acid could erase a body, but it could not erase every fragment. Haigh’s downfall was not only his greed but the triumph of forensic science over the illusion of invisibility.

About the Creator

E. hasan

An aspiring engineer who once wanted to be a writer .

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.