Reading Junji Ito’s ‘Army of One’ in the Age of Isolation

A lesson in connection, horror, and fishing wire.

I haven’t read manga in a long time.

My early teen years were spent feverishly tearing through shōjo series, such as Fruits Basket and Tokyo Mew Mew, all borrowed from my secondary school’s library. I remember proudly showing my aunt how to read them – “you go from right to left…” - when I visited for dinner a few times.

But those dappled panels couldn’t be further from Junji Ito’s work.

Disturbing and unflinching, Ito crafts horror that explores simple concepts – beauty versus bloody mutilation, deep fascination with the unknown, the grimly unexplainable in the midst of normality.

My first experience of reading Junji Ito was through one of his short stories: The Enigma of Amigara Fault. Much like the ill-fated victims urged to find the person-shaped hole in the mountain ‘made for them’, drunk on compulsion and folding themselves into moaning, fleshy masses – I was entranced.

In the vein of most psychological horror, Ito’s stories unwrap themselves like an unwelcome present. There’s a cold, unnerving weight under each detail revealed: a dark shape at the corner of a panel, the shaking hands of a previously infallible neighbour.

Pictured are normal Japanese communities ultimately morphed by disturbing imagery that lingers – a trademark of his style, the sharp fish-hook in the reader’s mouth on the last page.

...

So it was strange that his work, after years of neglecting manga, suddenly seemed so appealing to me during lockdown.

Within an hour, I’d used the burgeoning anxiety buzzing under my skin (ever-constant but worsened by England’s newest COVID reports and the US Elections) to chew through The Hanging Balloons, Long Dream, The Woman Next Door and Army of One.

Each one varies in lore and horror. Some stoke a deep, Lovecraftian fear of the universes within sleep. Others are violent and strange, with victims forcibly hanged by visions of their own disembodied heads in the sky. Your stomach roils. The mind reels, trying to grasp at some semblance of logic in the face of inescapable fate.

Often, Ito’s characters are left on the precipice of such an end. Death happens in many lurid ways.

There is the illusion of choice in some cases – the girl in The Hanging Balloons can choose to either stay inside and starve, or go outside and end up strangled by her own head. Neither are attractive options. But it doesn’t matter. Ito leaves us on the final panel with the protagonist faced with the corpse of her dead brother, lured outside by his voice, as her own noose swings closer.

But none coaxes the strange, syrupy anxiety brought from forced isolation like Army of One.

Army of One is a bonus story after the conclusion of Hellstar Remina and has proved to be one of Ito’s most popular one-shots, often said to be his magnum opus.

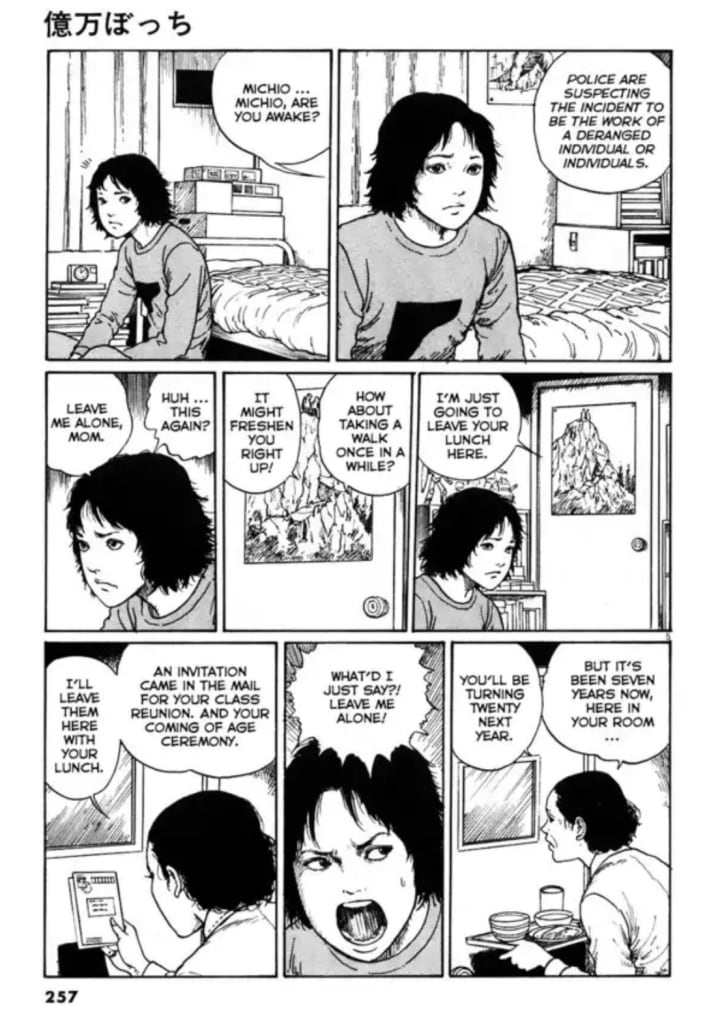

We view the plot through the eyes of Michio, a hikikomori (a person who remains shut inside the house and withdraws from society) – who has just been invited by a former classmate to attend a “coming of age” ceremony as part of a reunion.

While debating whether he should attend, the bodies of a missing couple are found in a lake, having been sewn together with fishing wire.

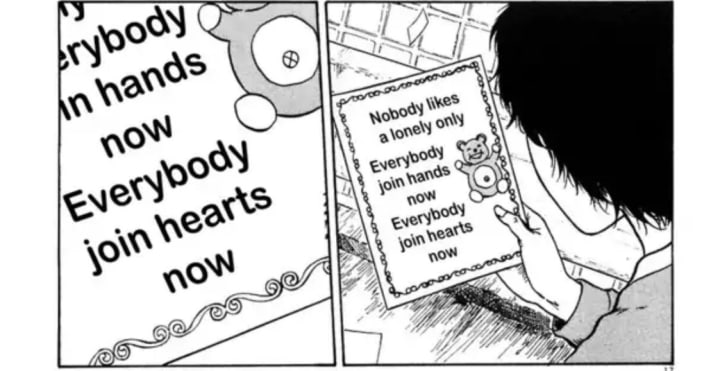

More grisly remains are found stitched together, growing in numbers and being found in more outrageous spots. Left in patterns, hundreds of people dangle from Christmas trees like bulbous strands of tinsel. A plane flies overhead and drops leaflets for the “Army of One”, which regularly advertises on the radio for new members; but does not provide any details.

A friend disappears after joining a singles mixer and turns up days later – garishly tied to the other attendees with the same wire.

The Army of One is deemed a terrorist organisation and large group gatherings are officially advised against, although the coming of age ceremony goes ahead and is heavily policed.

Michio is caught trying to sneak in to the ceremony to see if Natsuko, his long-admired crush, is safe. But when they arrive, all five hundred people who had been waiting for the ceremony are missing. They later turn up sewn together, including Natsuko’s fiancé Sakai.

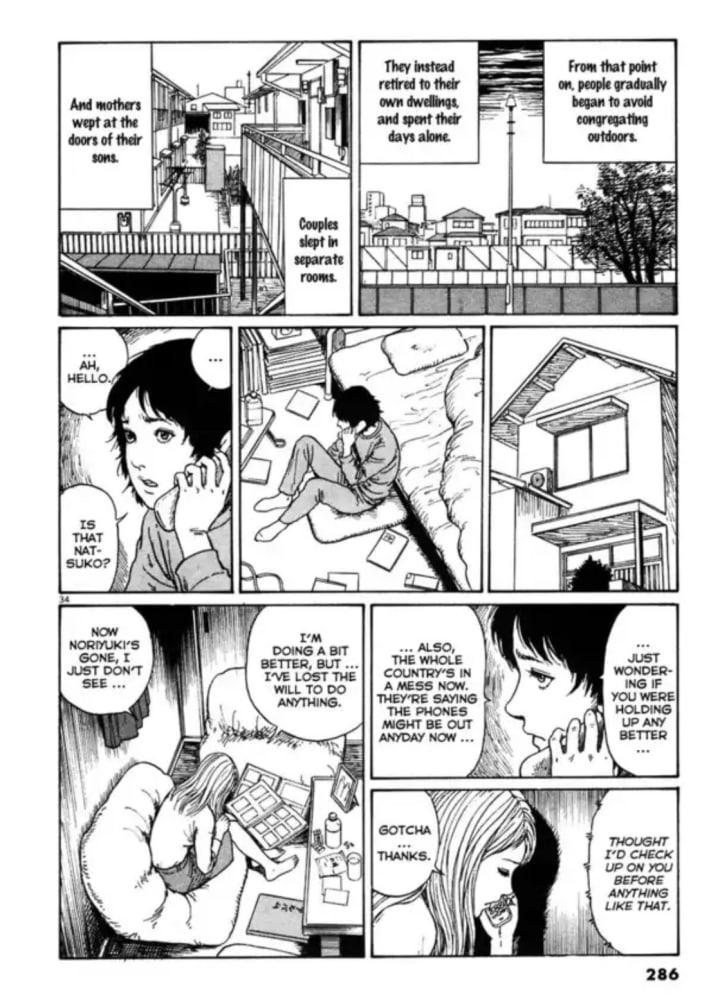

Following this, people avoid all forms of social contact or leaving the house. Even within his own home, Michio’s mother becomes secluded and they await the phone lines to be cut.

The mood is bleak. It’s upsettingly resonate.

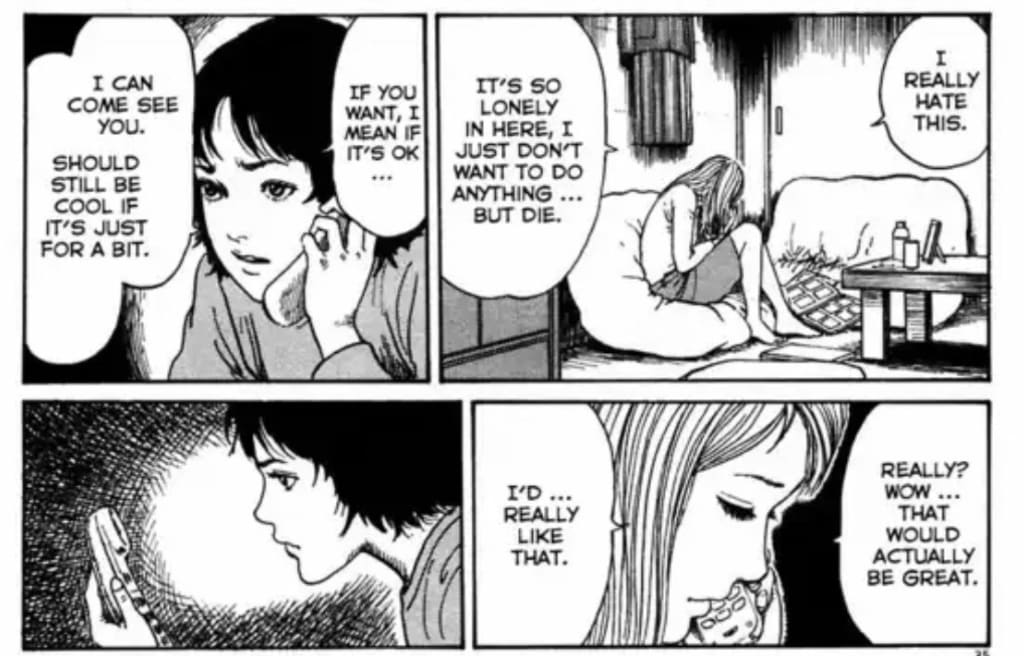

Michio calls Natsuko, and they both discuss the lack of contact and loss of their classmates and her fiancé. It’s a short and suffocating conversation, with both parties fringing on desperation. He decides to risk it and goes to keep her company.

In an uncharacteristically cheerful turn of events, the Japanese air force arrives to do aerial battle with the Army of One planes, who have been continually dropping flyers.

Michio, emboldened by the prospect of the Army of One’s defeat, runs over to Natsuko’s house to tell her he loves her.

As an audience, we know something is looming, finding ourselves too fraught to trust our narrator, our characters, this universe. That trust-your-gut instinct kicks into high gear.

And for good reason.

Michio finds her sewing the bodies of her parents and their dog together, singing the Army of One song to herself.

And crushingly, the military planes have somehow begun dropping the Army of One’s fliers as well.

...

Army of One, at its core, is a lesson in isolation. And it is easy to see why it has gained such a reputation. The core theme of staying sequestered away – by foreboding force – again, is a simple one, bolstered by some awful bodily horror that lingers behind the eyeballs.

But in the time of COVID, a similar creeping threat, this story becomes elevated parable. It also becomes all the more upsetting.

I found myself mirrored in Michio. As humans, we itch to talk and speak to one another. Even more so at our own leisure. So to have that taken away, at risk of losing one’s life? It’s an echoing sentiment.

“But God, even if he had survived, I probably wouldn’t be able to see him…

I mean, seriously. What’s the point anymore.”

Natsuko’s grief is palpable. There’s horror in the grotesque way death occurs in Army of One, but there’s also something to fear in the aftermath. That sense of a life, left in the lurch of a loved one’s passing, suddenly narrowing?

It’s masterfully done in a handful of panels, the loneliness of people pictured in different rooms in stark contrast to the way the murdered have been found – almost comically – stacked against each-other.

Closer than close.

Fiction has a way of taking on shape beyond its original intention. Army of One, one of the few Junji Ito stories that has no particular supernatural element (depending on your interpretation) is a claustrophobic nightmare of the reader’s own making.

We have no choice but to watch the events play out, further unwrapping those fateful actions that string us closer to the end of that sharp hook.

But with our own learned experiences of modern isolation, this is horror that now springs beyond the page. It beds in the brain.

And every desire to reach out, I hesitate.

I think of fishing wire.

About the Creator

Lauren Entwistle

Girl wonder, freelance journalist and writer-person. Also known as the female equivalent of Cameron Frye from the 1989 hit, "Ferris Bueller's Day Off.'

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.