“That sounds made up,” Adrianna scoffed. It was the first thing she had said to me all week, and it wasn’t even a conversation that she had been included in. I was speaking to Lily -- one of the girls who had taken a fondness to me since I landed myself in the Comfort Room. “I’ve known a lot of girls here, and not one of them said anything about no Open Mind treatment.”

“Maybe her situation is different than yours and mine, you ever think of that, Adrianna?” Lily snapped. “Not everyone here steals cars.”

“And not everyone here is here for sex crimes. What’s your point, Lily?”

“It was not a ‘crime.’ It was ‘allegedly’ a crime,” Lily said, using her fingers to accentuate which words were not hers.

“Then what the hell do you call a nasty old man sleeping with underage girls for cash?”

“Well, I-”

“-- and then trying to kill that old man in his own bed?”

“Allegedly,” I interjected.

“Thank you, Skylar,” Lily huffed. “And I have a type, big deal. I just have to pick better guys, that’s all.”

“Yeah, maybe start with seniors in high school, not seniors in the nursing home,” Adrianna cackled.

“At least I was having sex,” Lily snapped back.

“Yeah, you can miss me with that nonsense. I ain’t trying to have sex with nobody, least of all pedophile Santa.”

“It was one time and it was Aunt Faith’s fault for putting me that far up on his lap.”

“This is the worst conversation I’ve ever been a part of,” I gagged. “Can you please stop?”

“I’m just saying,” Adrianna deflected, as eager to change subjects as I was, “that none of our therapists use anything like that Open Mind stuff you’re talking about.”

“You don’t see Dr. Lau?” I asked.

“She’s a grief counselor,” Lily said. “And we don’t have grief.”

“Or shame, if you’re Lily.”

“Exactly,” Lily said. “No grief, no shame, and no regrets.”

I considered the implications of all this for a moment. How was it possible for Dr. Lau to only see patients for grief? Were there really that many other residents here dealing with a loss? There was a sense of relief in knowing that there were others in here with me dealing with the same shit, but I was disappointed that I didn’t know who they were.

“There was a girl a few months back that saw Dr. Lau, but she was the only other one that I know of since I’ve been here,” Lily mentioned. “Do you remember her name, Ri?”

Adrianna’s head tilted to the side. “Who told you that you could call me that?”

“I--I--,” Lily stammered. It was clear that she was genuinely caught off-guard and was not just trying to mess with Adrianna. “Tasha used that name and so I thought--”

“Yeah, Tasha used it. It’s not for you, white girl.”

“Throwing race into it, real cool,” Lily muttered.

“Stay in your lane and it won’t be a problem.”

“Fine,” Lily snapped. She tried to shove the table away from her, but it was bolted to the ground and she only managed to hurt her wrists. She stormed away from the table, leaving her plate of food half-eaten.

Adrianna shrugged. She looked over to me, and whatever expression I was giving her made her roll her eyes. “I don’t feel sorry for her. And you can’t make me.”

“I’m not trying to --”

“She thinks she knows every damn thing. If you don’t keep a girl like that in check, she’ll be unbearable. I’m telling you.”

“I believe you.”

Adrianna scoffed. “I thought that was gonna be the case with you, too. And it still might be. But you’re alright, as far as I’m concerned.” She tossed her fork onto her plate. “I dunno if it’s all this arguing or my new meds, but I’m not hungry anymore. You want any of this?”

Whereas I was a meticulous separator of food, Adrianna mixed all of her food into a sludgy mess. The yellow macaroni and blood-red Sloppy Joe mixture was unappetizing, and I shook my head. Adrianna shrugged and grabbed her plate and Lily’s to take to the sink. I sat for a moment, lost in thought. It’d been two days since my session with Doctor Lau. The nurses changed my dosage since speaking with her, and my mind felt fuzzy. It was getting more difficult to wrangle my disparate thoughts together -- like trying to assemble my grandmother’s Lincoln logs inside a spaceship to Mars.

It took longer than usual for me to register the tap on my shoulder and the voice of Mrs. Sherril beside me. I turned my head up towards her concerned glare. Her dark eyes narrowed as she tried to figure me out.

“You okay, Skylar?”

“Yeah… I was just spaced out for a second there.”

“Well, your mother is in the conference room waiting for you. She brought you some McDonald’s but I told her you were eating dinner already.” She lifted the bag to show me. “I can just stick this in the fridge for you if you want.”

“Why… are you being nice to me?”

“I’m always nice,” Mrs. Sherill snorted. “Just ask Paxton over there.” She pointed to a pudgy boy in the corner of the kitchen. He was feverishly counting the ants crawling through the crack in the barred window. He did not look in Mrs. Sherill’s direction, but he threw his fists up and down in a controlled fit.

“You made me lose count, Sherill,” he snapped in sharp monotone. “Mom said if I saw more than 50 ants at dinner time that she’d call the office and have this place shut down. I was at 29 and I missed at least three, thanks to you.”

“Okay, so maybe don’t ask Paxton,” Mrs. Sherill muttered. “Do what you’re supposed to do and don’t cause problems, and I can be the nicest lady you’ve ever met. Aside from your momma, that is.”

“Low bar,” I grunted as I pushed myself from the table and grabbed my plate. I dumped the half-portion of mac and cheese, as well as the entire sandwich, into the trash and handed my plate to the staff member at the sink. She muttered a quick thank you as I headed back to Mrs. Sherill. Mrs. Sherill had finished placing the brown bag of fast food into one of the three refrigerators in the kitchen.

After a quick sojourn to the restroom, I followed like an obedient zombie behind Mrs. Sherill. I kept my vision glued to the zig-zag gray pattern of the hallway carpet as we walked. I could feel my body attempting to sway with the movement of the lines -- my body was on autopilot as my brain struggled enough to process what I was seeing and hearing and couldn’t be bothered to worry much about what my limbs were doing.

We passed Dr. Lau’s office, but the door was closed. She only appeared during the week, so it was no surprise to find her office unattended. On the other side of the hallway, there was a doorway to an unfamiliar room with it’s door wide open. My ears caught a piece of conversation between voices of people I did not recognize.

“That isn’t what we do here, Mrs. Jackson.”

“You’re a Christian, aren’t you Linda?”

“I am, but we do not do that at Dogwood. You’ll have to take your daughter elsewhere.”

“No daughter of mine is gonna be shacking up with queers in this nuthouse! I’m pulling her ass out tonight! You hear me?”

The bellowing of the woman echoed down the hall as we picked up the pace to get as far away as possible, as quickly as possible. I could feel Mrs. Sherill’s eyes on me from the back of my head.

“I’m sorry you had to hear all that.”

“It’s okay. She’s not my mom,” I said dismissively. Most of what was said had not yet registered to me -- nothing more than words buzzing around my ears.

“True,” Mrs. Sherill admitted. “though maybe that’ll put your mom in perspective a bit, huh?”

“Doubt it,” I snapped back. I instantly regretted making any sort of small talk with one of these staff members. You give them just a tiny inch of you and they assume that they know everything about you. It reminded me of when my uncles would come to visit and it was clear that everything they knew about me they had learned from talking with my dad. They never asked questions to me about me. Not once did they show any real interest in learning about me -- they were just going through the motions and pretending as though they’d always been there. That they had never missed a beat. It was all so fake and forced, and I could have gone my entire life without it.

We rounded the corner of the hallway to the reception office. In one corner of the room was an abandoned reception desk -- bare and clinical. The thick glass windows by the front door were stained yellow with age and neglect. It was a wonder that my mother ever walked me through the front door and approved of this scene.

Mrs. Sherill gestured towards a closed door on the left side of the office. She knocked on the door twice and opened it to let me in. There were four round tables with hard plastic chairs around them, and my mother was at a table on the far side of the room. She looked up at us and plastered a weary smile across her face.

“If you need me, I will be right outside this door,” Mrs. Sherill announced to us.

“Are you just … going to sit out there?” I asked.

“It’s my favorite part of the job,” she joked. “I get to sit on my behind and listen. No dishes, no laundry, and no hassles.”

“Hopefully not,” my mother interjected with a strained laugh. She gestured to me to come over and sit with her and I followed along. She outstretched one of her arms, beckoning for a hug, and I chose to sit across the table from her instead.

“That’s fair,” she muttered. “This can’t have been easy for you these past months.”

“You would be right about that.” I folded my arms. She stared at me, her dark eyes piercing through my guard and challenging me. This was a much different approach than I would have guessed from her, and maybe it was just the medication, but it worked stunningly well. I let out a defeated, aggravated sigh and unfolded my arms.

I recalled one of our early group sessions with all the residents. I had just started to remember the days and had been allowed to rejoin the group for the first time -- my crimes that caused my exile in the first place were never clearly presented. Each week, one of the therapists would pull the short straw and be tasked with giving a group presentation over some sort of emotional management skills for that week.

Doctor Jameson, for all his infinite wisdom of the human condition, communicated all of that wisdom with the joy and enthusiasm of a half-baked sea slug. There was, however, one nugget of wisdom -- likely taken from a Snapple cap or some such bullshit -- that breached the surface of my mind in that moment:

If you cannot make the effort to trust others, why would they ever extend that trust to you?

“Thank you for coming,” I said through gritted teeth, loud enough for Mrs. Sherill to hear. “And for the dinner.”

“Of course,” Mom cooed. “I know I would want some McDonald’s after not having it for a bit. I was going to get one of those ice cream things with the Oreo’s in it that I know you like, but the machine was down. Go figure, right?”

“It’s always down,” I muttered. She chuckled, and it felt nice to laugh with her in that moment. I cannot stress enough how much the medication may have influenced our meeting together, but whatever the cause was, it was a pleasant change. I wondered why things couldn’t always be like this.

“I did bring something else for you, but Donna at the front desk said it would need to be checked in at the front desk.” Mom turned from me and rummaged around in a large black duffel bag that she had brought with her. She lifted my father’s guitar over her head and placed it gently on the table. Her eyes lit up as she caught the smile that crept across my face. She nodded eagerly and wordlessly ushered me to pick it up.

I strummed a couple chords, and my head tilted. I looked up at her and made a face to communicate what I knew she could not detect with her own ears. “Will need to be tuned for sure.”

“Are you able to do that without some tool, mija?”

“Oh yeah, Dad taught me how to tune by ear. It just takes a minute.”

“Oh good,” Mom said with a sigh of relief. “I didn’t know what all you’d need with it. I did grab one of those little picks to go with it.”

I jostled the guitar to discover that it had fallen into it. I laughed under my breath at the look of horror on Mom’s face.

“Will that be a problem? I put it under the strings so I wouldn’t lose it but it must have--”

“It’s not a problem, Mom.” I shook the guitar from side to side until the pick dropped from the sound hole. It was one of the makeshift picks that Dad had made from an old credit card. It was crude and jagged, but knowing that he had cut it made it special to me.

Mom took a sharp breath in, and I knew that she was building to something that I absolutely did not want to hear. I decided to take the burden off of her shoulders and address it directly so that she wouldn’t have to.

“What’s wrong?”

Mom stared at me with pain in her eyes. When I took a minute to really look at her, I was able to notice how swollen and red her eyes were. Mom was always exhausted from work, but this was something else entirely.

“I know that you never met her, but my mother -- your Grandma Mariana -- is in the hospital. When we spoke on the phone the other day, I had just found out that she was there. Since she had no other children or relatives to speak of, and my father passed years ago, the hospital reached out to me as the last point of contact for her.”

“What’s wrong with her?”

“I’m not sure. Something to do with her heart. She’s been in a nursing home for years, but she had some sort of chest spasms that landed her in the ER. In any case, the doctors say that she is stable but in and out of consciousness.”

“Did you talk to her?”

“Just once. And I know that what I’m about to tell you is insane but I need you to believe me when I tell you this.”

“I have a pretty high tolerance for crazy stuff these days,” I said.

“She asked that I give you something. Something that she has been holding onto for decades. She asked for you, by name.”

My eyebrows raised in disbelief and my arms folded. I leaned back in my chair and scoffed. “How the hell does she know my name? I thought you haven’t talked to her in years?”

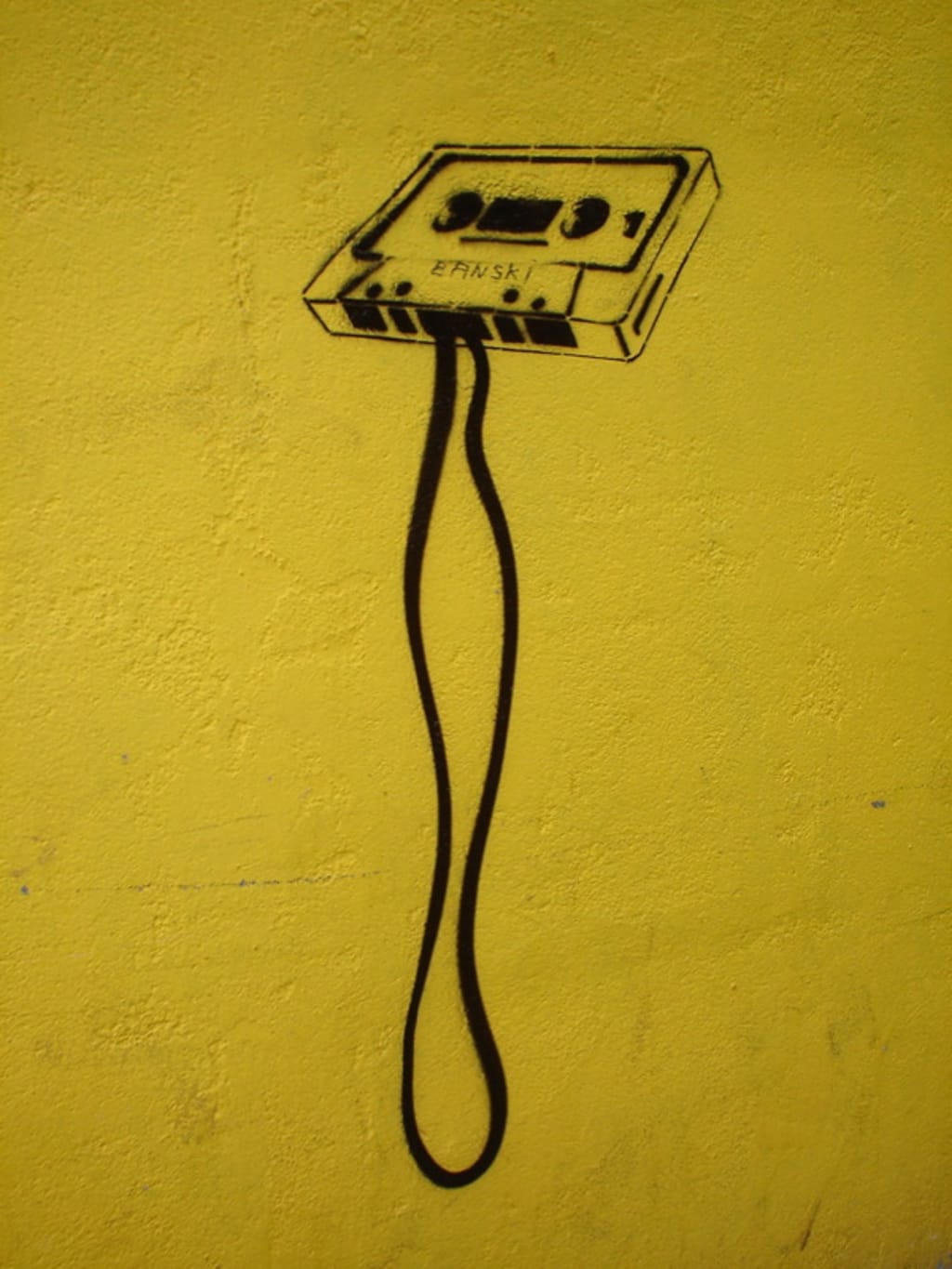

“I haven’t. But apparently your father has.” Mom reached into the chunky leather purse on her lap and pulled from it an old cassette player. She slid it across the table to me and I picked it up, turning it over in my hand. It was a scuffed, blue Sony Walkman. There were a pair of gaudy orange headphones attached to it.

“Grandma knows that they stopped making these like, a hundred years ago, right? Can’t exactly walk around blasting old Tejano music with this.”

“When we were in high school, your father was not shy about letting his feelings for me be known. Everybody knew that your father was in love with me, which was a bit of a problem for my boyfriend at the time, Alejandro. It was a problem for my parents, too. They wanted me to be with a strong, handsome, hard-working Mexican boy like Alejandro -- not some pudgy, lily-white bolio like your father.”

“That sounds like Dad all right.”

“Well, your grandpa Abner was also not keen on his son getting involved with any girl who wasn’t blonde with blue eyes, so he took a trip one night to my home and our fathers got into a horrible shouting match. Called each other every name in the book. The whole thing was ridiculous because they were ultimately arguing in favor of the same thing -- that your father and I would never be together. But men don’t need things to make sense in order to get into an argument.

All of this never stopped your father, of course. It was the week before the big homecoming dance and Alejandro hadn’t bothered to ask me to it. Your father caught me on the way home outside of my house, pulled out his guitar, and played a love song for me that he’d learned in Spanish. After he was finished, he got down on one knee -- which was a challenge for him even in his prime -- and asked me to that dance.”

“And you said yes?”

“Well, no. But then Alejandro stood me up anyways, so that was my own damn fault, really.”

“Wow, Mom.”

“He did get me to go with him to prom, so it all worked out in the end. But my point is that the song he played for me on that day is recorded on that cassette player. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve listened to it since my mother gave that to me last week.”

A few stray tears fell down my mother’s cheek, and she wiped them away with the back of her hand. I grabbed the cassette player and shoved it in my pocket. Mrs. Sherill came into the room to inform us that the cassette player would need to be checked in as well, but she assured us that I should be able to keep it since the cord was under the length that would be required to hang myself.

“Thank you for that uplifting reminder of where I am,” I deadpanned as I handed the cassette player to her. “You see what I have to deal with here, Mom?”

“I said it before and I mean it, Skylar. I just want what is best for you. And I think, at the end of all this, you’ll be better for it. Your father wanted that for both of us. He loved us more than anything else in this world, and all I want is for you to love yourself just as much.”

“Maybe someday I will get there,” I said.

At that moment, the front door chimed to the reception office. Mrs. Sherill looked panicked as she dashed to the door. I could faintly hear the sound of a man on the other side of the wall.

“It was unlocked! What kinda security is that?”

“Sir, you cannot just come in here and --”

From around the corner of the door popped Dave’s head. It was even uglier than I remembered.

“Oh, sorry,” he muttered. “I didn’t know if ya’ll were done in here or what.”

“Dave,” Mom snapped in a tone usually reserved for me, “I told you I would come out when I was ready.” Mrs. Sherill turned away from my mother to say something else to Dave, but Mom cut her off. “He’s fine. He’s with me.”

“He really shouldn’t be --”

“We will be out of your hair in just a minute.” Mom turned to face me. She took a sharp breath in and tossed her long hair from her face. “Do you mind to wait outside while I talk with Mrs. Sherill, Sky?”

“Sure,” I shrugged. I left the items that my mother had brought on the table and walked outside of the cramped conference room. There were a pair of chairs on the wall outside the room; one on either side of the conference room door. Dave sat in one of the chairs, and I sat in the other. We said nothing for a moment -- we may have both been trying to eavesdrop on my mother and Mrs. Sherill speaking, but their hushed tones were too soft for either of us to hear.

“You know, you sure are handful for your poor mother,” Dave whispered.

I scoffed. “Excellent observation, Doctor Phil.” I was fixated on the shiny reflection of his bald dome. Even in this dim light it was bright. “She’s not exactly a walk in the park either, I’m sure you’ve noticed.”

“And a mean little shit, too,” he laughed. “Remind me of me when I was your age.”

“You don’t know the first thing about me,” I snapped. Another person assuming that they know me. The worst person assuming they know me. “Do you even know my age?’

“Testing me, huh?” Dave rubbed his hands together like an ape anticipating a mushy banana. “Okay. I’m gonna say … 14?”

“16.”

“Huh,” he popped off with mild bemusement, “I could have sworn she told me 14. Are you sure that she knows you’re 14?”

“My mom is a whole lot of things, but forgetful is not one of them.” I shot a glance over to Dave. “You might want to jot that part down.”

“Noted,” he chuckled. He said nothing for a few moments, seemingly content with the silence. The only sound was the murmuring of the women behind us and the buzzing of the air conditioner on the opposite wall. “She really does love you. Might be a bit messy and tough sometimes, but she does.”

“I know she does,” I groaned. “Just because she loves me doesn’t mean I have to make excuses and lie to myself about when she’s being terrible.”

“That’s true,” Dave admitted. “My mom used to beat the ever-loving hell out of me when I was a kid. Spent a lot of time thinking I did something wrong, like I’d done something to deserve all that. But that wasn’t love. Nothing my momma ever did, the good or the bad, came from love. Everything that your mom does is out of love, though. I can tell you that much.”

“She has a funny way of showing it.”

“So do you,” Dave laughed softly. “So try to give her the benefit of the doubt that you’d want for yourself, okay? You’re both learning.”

“Wow,” I said, “you really are Doctor Phil.”

Dave laughed, in spite of himself. He shot me an look of admiration. “I’m serious. She’s got a big calendar in the kitchen with your target dismissal date on it. Every time they call her, she scratches out the old date and puts up a new one. She wants you to come home so badly. I guess she found out that you really don’t know what you’re missing until it’s gone. I’m sure you can relate to that.”

The goodwill that Dave had bought with me up to that point deflated like a sorry balloon. I felt the floor give way beneath me and my head began to swim. My voice was small and quiet, “don’t talk about my dad.” I stood up --my feet unsteady and my legs wobbling -- and walked over to the reception desk. I could sense Mrs. Sherill’s eyes on the back of my head; her concern about what I might do evident.

“I’m not your dad,” Dave said, cautious and thoughtful with each word. “I couldn’t be. I’m not trying to be. I’m just Dave.”

“Then leave my mom alone.”

“She doesn’t want to be alone, Skylar. Do you?”

“Right now, that sounds pretty good.”

I walked down through the double doors back into the hallway. I could hear Mrs. Sherill calling after me but I kept walking. I kept my pace slow and steady -- I knew that running would only make her more angry. She caught up to me quickly, though just the small bit of hustle made her winded. She had the duffel bag in one hand and a set of paperwork from the reception desk in the other.

“I thought we had an understanding that you stay in eyesight, Skylar.”

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Sherill,” I admitted. The apology was genuine, and it seemed to catch Mrs. Sherill off-guard. “I just couldn’t be in that room with Dave any more.”

“I understand, Sky.”

“No, you don’t,” I replied shortly. “And your not my mother. Don’t call me that.”

She picked up the pace to cut me off. She stood resolute in front of me. “Let’s get one thing very clear. Your mother may let you talk to her that way, but I will not. I am sorry that I called you a name that is not for me to call you, but that doesn’t give you permission to bark orders at an adult like that.”

“If you want me to talk to you like an adult, don’t talk to me like a child.”

“As an adult, I’ll talk to you however I see fit.”

I scoffed and made a motion to walk around her. “That hardly seems fair, Mrs. Sherill.”

Mrs. Sherill opened her mouth to argue, but before she could say another word, shouting erupted on the other side of the double doors that led to the residential hall. She stumbled backwards just in time to avoid the doors flying open. A woman, whose voice I had heard in the conference room on my way to meet my mother, stormed through the open doorway. She had one of the residents, Tasha, in a firm grip as she led her down the hall.

“I ain’t about to let ya’ll raise my daughter to be a black woman who don’t know God. This place is of the devil and we ain’t havin’ no part in it.”

“You gotta let me say goodbye, Momma,” Tasha cried out. Our eyes met for a brief moment, and I could see her pain and anguish. Tasha never looked happy in all the time that I’d known her, but I’d never seen her look so miserable.

“We are not wasting another breath on these queers,” her mother spat. “We are going straight home till I can find someplace to put you that isn’t godless!” She shouted the last word at the staff with all of the force and venom that her ample chest could muster.

Mrs. Sherill shot one quick glance at me and dashed over to the residential desk. I followed behind her. Her hushed tones with Donna, who was seated behind the desk and frantically dialing on the telephone, told me that I needed to leave. I headed down the hallway, numb and drained. I turned the corner and could hear the familiar sound of Adrianna’s voice echoing from far down the hall. As I proceeded down the hall, I discovered that her voice was coming from the Comfort Room down the hall.

“You didn’t even let me say goodbye, you assholes!” She cried out in a way I’d never heard from her before; or from any of the other girls for that matter. It was a guttural, painful cry that rips through you from the pit of your soul. It was the kind of cry I’d only experienced once -- after I found out that Dad had died. It’s the kind of cry that echoes loudest through those who have experienced that kind of sorrow before. I felt her pain as if I’d felt it myself, and it was overwhelming. I threw myself into my assigned room and collapsed on the bed. I tried to cry, to alleviate some of the pain, but there was nothing in me. I just felt empty.

I don’t know how long I had been laying there before the screaming finally stopped. I faded in and out of consciousness. At one point, I heard a faint knocking on my door. I’d left it wide open, but one of the only people who bothered to knock on my door was Mrs. Sherill. I turned slowly to find her standing in my doorway. She held the Walkman in her outstretched hand.

“I know it’s a bit late for drowning all that noise out, but I figured you might still want to have this tonight. Just be sure to check it back in to the resident desk in the morning, okay?”

I couldn’t manage any words, but I nodded gently. I rose to my feet with some effort and grabbed the cassette player from her. I offered a meek thank you and returned to my bed. Mrs. Sherill closed the swinging door behind her, but I managed to call out to her. “Mrs. Sherill?”

Mrs. Sherill turned around quickly and peeked her head over the top of the doorway.

“Can you show me how to work this thing?”

Mrs. Sherill chuckled and came into the room. She explained that, in a previous life, she’d been a preschool teacher. Being able to teach me how to rewind the tape and play it, she told me, reminded her of that time. I imagine that, in a different time and different place, I might have liked to have her as a teacher. When she’d finished with her demonstration, I thanked her as she walked back out the door.

I wasted no time in putting on the headphones and allowing the tape to play. At first there was nothing, and then I could hear the unmistakable baritone of my father’s voice. It was overwhelming.

I’m s-sorry I am not the one you want for your daughter, Mrs. Perez. There are things I can never be for Deborah. Things I would ch-change if I could. But my love for her is one thing that will certainly never change, and…and I couldn’t change it if I tried. I hope that your family might give me a chance to prove that to you.

He strummed the guitar earnestly, if a bit flat. The change in volume was shocking, and I regretted that Mrs. Sherill did not teach me how to turn the volume down. I scrambled with the player until I found the volume controls. I imagined my grandmother with the same experience. After a few more strums of the guitar and the clearing of his throat, Dad spoke again:

I spent a whole week learning this song for Deborah. I’m sorry if my pronunciation is really white -- I haven’t heard much Spanish o-outside of my class at school. B-but I want to speak directly to your heart, in your language, because I…I want you to know how much this means to me.

This was a side of my dad that I’d never heard before. The stuttering and stammering was something that he’d grown out of it, it seemed. In my memories, Dad was always so confident and self-assured, but here he sounded so small. But there was no mistaking his intention -- his spirit was still in it. He started to play the guitar again, and a bright melody took shape. It was a song I’d heard many times on the radio -- a song I’d heard Mom sing many times, but I’d never heard it from my dad. He started to sing from the chorus:

Amor prohibido murmuran por las calles

Porque somos de distintas sociedades

Amor prohibido nos dice todo el mundo

El dinero no importa en ti y en mí, ni en el corazón

Oh, oh, baby

El dinero no importa en ti ni en mi

Ni en el corazon oh, oh baby

Aunque soy pobre

Todo esto que te doy

Vale mas que el dinero

Porque si es amor

Y cuando al fin

Estemos juntos los dos

Que importa que dira

Tambien la sociedad

Aqui solo importa nuestro amor

Te quiero

After the last notes, the recording cut out. I listened to the empty static for a few minutes, hoping that maybe there would be something else. I hit the rewind button on the recorder and replayed it over and over that night until I fell asleep.

AUTHOR NOTES:

English Translation:

"Forbidden love", they murmur through the streets,

Because we're from different societies...

"Forbidden love", the whole world tells us;

Money doesn't matter to you nor to me,

Nor to the heart… Oh, oh, baby!

Although I am poor, all of this that I give to you

Is worth more than money, because it is true love…

And when finally we are together, the two of us,

What does it matter what they'll say, society too?

Here, only our love matters - I love you!

https://lyricstranslate.com

About the Creator

ZCH

Hello and thank you for stopping by my profile! I am a writer, educator, and friend from Missouri. My debut novel, Open Mind, is now available right here on Vocal!

Contact:

Email -- [email protected]

Instagram -- zhunn09

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.