When I was born into this world, I had no idea that I was destined to die. I went through most of my early years with no idea that at some undetermined point in the future, it would end. Each day felt like an adventure, new toys, new things to do, new things to hear, new things to see.

After surviving health scares, visits to hospital and operations that saved my life, after brief experiences of near death under anaesthetic and hearing about sick people my father helped (he was a medical doctor and very talented at diagnosing a disease as though he had a sixth sense) one day that was no different at first to any other, a mother gathered her children to hear how they had lost their father who's heart had exploded late last night during a patient visit. I was a little over eight years old and this was my first real experience of death. I searched within my little soul and could not find a reaction except curiosity, and asked how it happened. I accepted the explanation in a matter-of-fact way, and then thought about the rest of the day. It was weeks later that I realised I would never see him again. It was nearly twenty years later that I felt the grief of loss.

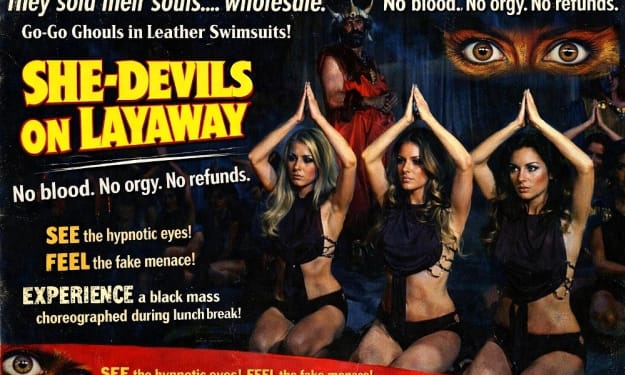

And how, it has been a lifetime of not getting to know my father. His missing parts still haunt my dreams. The other night I was on the operating table and he was inserting the blade to my heart. It was beating and my chest was open and I was awake. He was explaining to the young interns gathered around the gurney that how you hold the scalpel matters, the angle of the blade was a matter of precision. "Even a small incision can go wrong if you hold your instrument incorrectly," he instructed. "Just a small incision, there." His death had resulted in his promotion and retraining from General Practise to that of being an experimental surgeon in a horror film, complete with gaudy music and a chorus of gown wearing skeletons.

I look my partner in the eye and say, it is time to find a doctor. The rash on her arm had turned colour and her eyes were dull. She felt exhaustion and refused help. "What can they do?" she protested. "I doubt they can do anything." I resigned. And that night my father returned, driving a wheel barrow and asking for the bodies of plague victims.

And then I lost my two sisters. Both in the same accident. They were in the front seats of Patricia's sporty wagon when a lorry careened across the path they were travelling and the engine crushed both their bodies. Death came instantly. It was a few months later, six actually, almost to the day, that Pat and Laurie joined into the medical nightmares. They were broken and Dad was wielding his famous scalpel and said "don't worry, I will save what can be saved. You may have to share an arm, there are not enough legs, one of you will do without."

Clearly, death had taken its toll on my mind, my emotional state was a delayed reaction and the problem was simply getting more profound as I edged closer to my own release from this life, my life was becoming more and more tortured.

So I sought help. I rang a few therapists who refused to take on my case when I told them my name. However when I rang Dr Crispin everything changed. The phone call went too well. He took an interest in my case which only made me suspicious. I was however in need of help and his direct questions resulted in my talking and revealing a little too much.

That afternoon there was a knock at the door. Proverbial men in white coats arrived and bound my wrists and put me into a restraining jacket. Crispin then walked in and recorded my vocal consent that I needed help.

I was in the van and arrived at a country hospital with balustrades and towers that peered into the heavy clouds that made the evening feel ominous and strange. The sharp jolt of a needle in my arm then dissolved the world.

I woke up on the gurney. I could not move. I could swivel my eyes and caught the flash of the scalpel in the surgical beam which turned everyone peering over me into ghastly shadows. "Just a small incision," that voice I had forgotten that felt familiar to my bones and the line of gowns lining the wall, looking on. I could not hear my own screams.

And now I am about to wake up in a hospital bed. I do not know what I will see when my eyes open and focus. I can feel a hot light bearing down on my skin and hear muffled voices discussing me and my fate.

But my eyes will not open. I will not wake up. It is here that I must die. The reality that I must reconcile with must be too terrible to see. My eyes will not open. I can not wake up.

And I do not wake up. Not ever.

About the Creator

Nicholas Alexander

Poet and writer of horror, science fiction, literature and political commentary.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.