THE 2ND MONTH

Madeline dreamt she could fly. Above the hills and under the sun she soared. Annie was her co-pilot. They soared to heights where birds could only strain their stunted necks and look up at them with envious glares. She, with co-pilot in hand, spun and danced among the clouds, all-the-while bathing in the sun’s warm, fresh rays. She looked up at it and it didn’t hurt her eyes. They seemed invincible. She felt she could touch it. And she tried. Reaching higher and higher, her heart beat with excitement. She put her finger on it.

Tap. Tap. Tap.

It sounded like glass.

Tap. Tap. Tap.

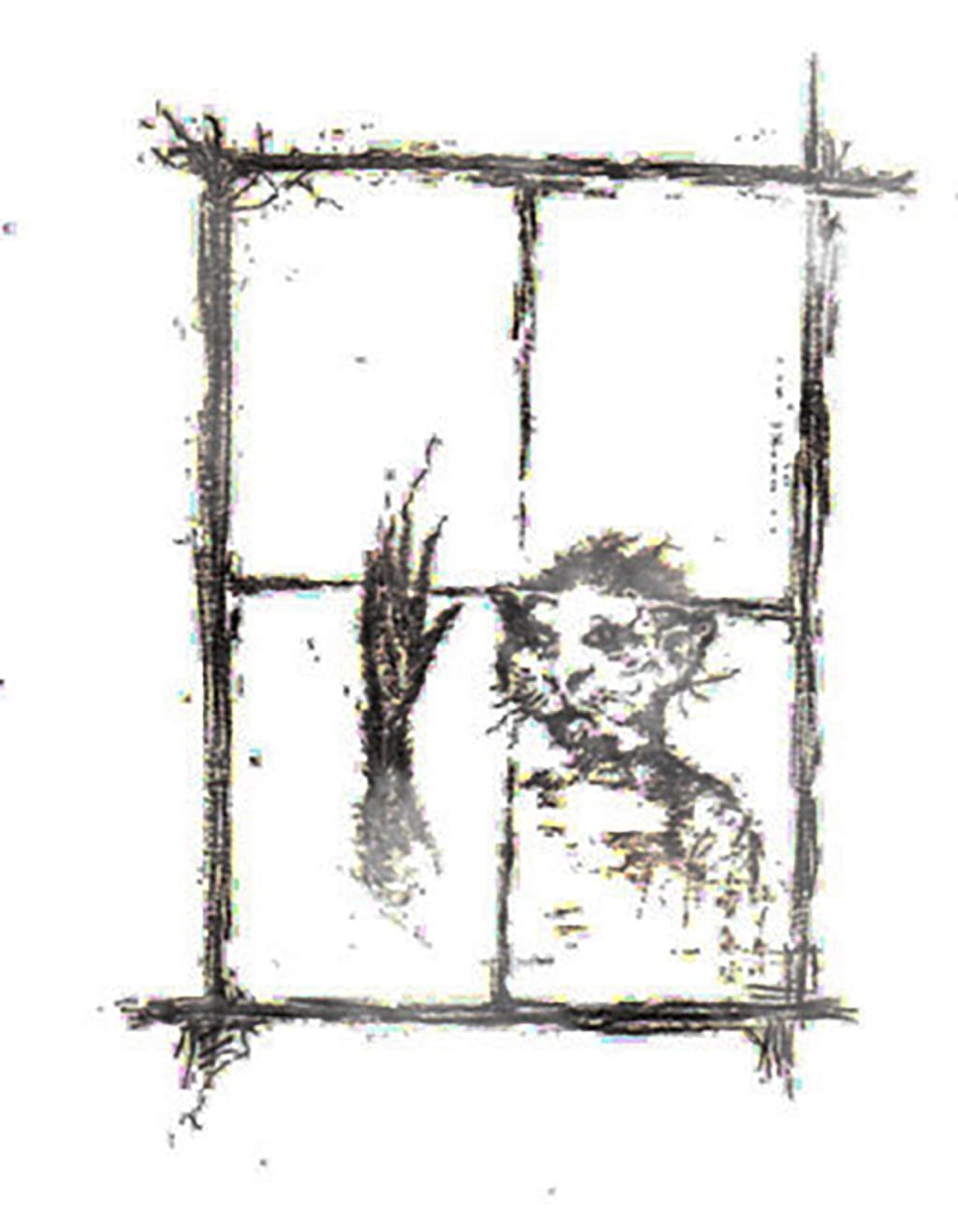

She woke up from a dream that now made no sense. She looked around the room as her eyes adjusted. She looked over to the strangely dimmed window in her room and froze.

There looking in at her was a face.

Its eyes shined and flashed. Its nose was flat and its nostrils wide as it purred and cooed. Long, wiry strands of hair hung loosely from underneath those nostrils, swaying gently with each breath it took. It lifted its arm and pressed it against the glass.

Tap. Tap. Tap.

Madeline screamed. This time it was louder than before. Her parents came into her room in the same manner. Again, the toy chest compromised Mr. Drery’s shin.

“Oh my, honey, another bad dream? What happened,” her mother asked.

“No, no, no bad dream. It’s real. I saw it again. It was looking through my window.”

The two looked over at the window, but nothing was there.

“Honey, there’s nothing there,” her mother reassured her. “Do you want to sleep in our bed again tonight?”

“I want you to believe me. I really saw something,” she pleaded.

“Okay, okay, Skipper,” her father assured. “Tomorrow I’ll take a look around again. Maybe there’s something around that can help us solve this, okay?” He looked at her and wiped fresh tears from her cheeks.

“Okay,” she replied.

“Let’s go, then.” He took her in his arms.

“Don’t forget Annie!”

Mrs. Drery walked back inside the room and over towards the window where Annie lay, lifeless. She briefly looked outside the window before she bent down and picked her up.

“What a strange, little girl we have,” she said to herself as she turned around, looking

out the window just before exiting her daughter’s room.

“Strange.”

The rest of the night progressed, Madeline’s sleep was uninterrupted, save for a few whimpers she let out as the slept rather soundly in her parents’ bed. Her dream of flying now became like a nightmare of falling, that thing’s twisted, grotesque face still stared at her. Though it was physically gone, her mind and dreams were still stained by its presence. She moaned and cried in her efforts to fight it off. There, inside her head, it came too. It moved in awkward agility, head bobbing up and down through the mist as it had done before. It came closer, ever so slowly, disappearing one second, then re-appearing the next. Always closer, always advancing. Then as it leaped to pounce upon her, she opened her eyes and vanquished it from her mind. But a finger’s length away laid Annie, round black button eyes looking into hazel retinas.

“You’ll protect me, I know you will,” she whispered and hugged her doll.

The next morning, Mr. Drery fulfilled his fatherly promise to his daughter and took her out back to the side of the house where her window was.

“There is where you said it was, Skipper?” He pointed to her windowsill.

“Yes, it was looking right at me, through my window,” she replied, concerned.

Drery examined the glass at the ground immediately below where her window resided.

Nothing.

Not a single track or scrape was left by any fleeing animal or creature that would require such speed to have disappeared so quickly as to avoid detection. Not one.

“You say it was up there outside your window looking in at you, Skipper?” He pointed once more.

“Yes, Daddy. I swear it.”

A perplexed look came upon Mr. Drery’s face. His brow cringed at his quandary.

The way any animal, be it wing or claw, could hoist itself up to hang or even perch upon the sill was nearly physically impossible. The sill measured about two inches from the window’s glass. That was hardly enough room for a bird of even the most minute size to perch. All of the birds Drery’s seen around this countryside have been crows and the occasional jay. They were much too big for a sill like that. There was also no lattice, no vines, no nearby branches or even a latter by which one could hoist itself up. It was bare, smooth siding from foundation to roof.

As Drery examined and considered this impossibility, his eyes caught sight of something that moved with the odd stirring of breeze. It was right below his daughter’s windowsill, but he couldn’t quite make it out. As if he had not a moment to spare, he ushered Madeline to follow him and, with haste, ventured up into her room. He walked to the window and unlatched it. Though the wooden frame that cradled the window had aged and tightened its grip on it, the window slid upwards with considerable strength applied. Drery leaned out and, with minimal effort, snatched the object from a loose, twisted nail. It was another tuft of hair. This time, though, black was prominent and gray was sparse amongst it. There was something else, something stranger than the fabric that the last tuft hosted. It almost felt wet. Mr. Drery held the hairs up to the light and saw what appeared to be a dark red substance. Blood. Madeline looked at her father, then at him and he returned her gaze.

“See, what’d I tell you.” She pointed at the hair and then the blood. “See?”

“Yeah, Skip, I see.” He paused for a second.

“I don’t know what was up at your window or what this came from or even how it got here exactly, but I’ll talk to mommy and we’ll set up a place for you in our room for a while until we can figure this thing out, okay?”

She nodded and smiled wide.

“Okay, Daddy.” She thought for a moment. “There’s room for Annie too, right?”

“There always is.”

Mr. Drery put his new discovery in his jeans pocket and brought Madeline back inside. He thought all the while. Something strange was going on. He remembered the old man’s story and what he said about missing children. He didn’t quite believe him yet, but he feared he was heading there. The vacancy of animals in the area, and yet tufts of hair that resembled such had appeared. Right after his daughter had dreamt or witnessed some animal-like thing in the vicinity where these strange tufts of hair were found. It made no sense. But was it a father’s obligation to protect his family, especially his children, from their dreams or imaginations? Mr. Drery thought so. In fact, he believed that no bad could come out of a little extra precaution.

With that in mind, he found himself once more upon that broken, dirt path that crossed the road and ended up at the old man’s house. And there before him, as he progressed up the path, did Mr. Cobbs appear, savoring a breath of tobacco, before letting it out into the world.

“Mr. Drery, how does this day serve ya,” the old man called out.

“Well,” Drery replied, “pretty good, I suppose.”

“What be on yer mind, there Drery? I seen that look in yer eyes when you comin’ up here the first time with that look on ya,” the old man asked.

“Well, my little girl had another bad dream. The same kind as last. Only, this time this thing she said she saw was right outside her window.”

“I thought’cha didn’t believe in such nonsense there, Mr. Drery,” the old man replied.

“Well,” Drery responded, “I usually don’t. But –“

“But, what?” The old man’s curiosity aroused.

“But, I found this outside her window.” Drery pulled out the black and white tuft of hair from his pocket and showed it to the old man. He just looked at it a moment, then spoke.

“Looks like it’s a bit red at the end, there.”

“I know. I think it’s blood. See.” Drery lifted the hair up to show Mr. Cobbs.

“I think it snagged itself on the nail I found this on,” Drery said.

“Well, how may I help ya here,” the old man asked.

“I, I really hate to ask you, Mr. Cobbs, but, I was wondering if I may pay you for use of your Winchester over there. My wife doesn’t like me to keep guns in the house on account of our daughter and all, and…”

“Didn’t yer father have guns? I thought he did. Seemed like the type,” the old man interrupted.

“Well, he did, but he sold them off years ago. Never felt the need for them. Too quiet and secluded out here I suppose,” Drery replied.

“Here’s where you’d need ‘em the most. Strange things happen in quiet towns. Like whatcha got there in yer hand.” The old man pointed to the tuft of hair nestled in Drery’s fingers.

“Well, I suppose you got me there, sir,” Drery replied.

“I tell ya what,” the old man said as he bent over to pick up his rifle. “Ya can’t borrow ole Chester here. He’s the last thing I got. Just him an’ me here. An’ me fiddle, of course. But, if the legend be true an’ that thing come ‘round when the moon be sharp lookin’, like a sickle, that’s when ya have me protectin’ ya. How’s that do ya?”

“What’s your price,” Drery asked.

“My price be a bit of company, a bit of yer wife’s cookin’, an’ a place on yer porch.”

Drery stopped for a moment to consider it, then nodded his head in agreement.

“That sounds alright by me.”

“Ya don’t mind me fiddlin’ while I watch do ya,” the old man inquired.

“Nah, I was actually thinkin’ of bringing that up myself. Besides, I’m sure it’ll help Madeline fall asleep. She really took to your fiddling when you came over last.”

“Well then it’s settled,” spoke the old man, his voice full of glee. “I be yer hired gun an’ yer wanderin’ minstrel.” He laughed at his joke and sat down in his rocking chair.

Drery waved goodbye to him and headed on back.

“I be seein’ ya next sickle moon, Drery,” the old man called out.

By this time, Drery had crossed the street and was approaching the door of his home to inform his family of their deal.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.