Dawn of the Dead is one of the most tedious horror films ever made—at over two hours, it seems like an interminable experience, shambling along like (if you’ll forgive us) the walking dead until the inevitable apocalyptic conclusion.

It is a film with enough sadistic violence, blood, gore, action sequences, and killings to satisfy most—but these are stretched between banal scenes in an abandoned 1978 megamall where legions of zombie extras in pale makeup walk stiff-legged through the aisles while being clocked by gun-wielding refugees who escaped Philadelphia in a helicopter.

The foremost of them, and the film’s most memorable figure, is SWAT team member Peter Washington (Ken Foree), who went on a few years later to star in Stuart Gordon’s excellent H.P. Lovecraft adaptation From Beyond (1986). He is joined by his partner Roger (Scott Reininger), “Flyboy” Stephen (David Emge), and the pregnant Fran (Gaylen Ross). Alighting atop a shopping mall in Pennsylvania—already infested with hordes of shuffling undead, including a Hare Krishna prominently displayed as a satirical dig at cult-like devotion—the four barricade themselves inside. In the belly of the beast, they enjoy the luxuries within, which leads us to the film’s not-so-subtle critique of consumer-culture capitalism.

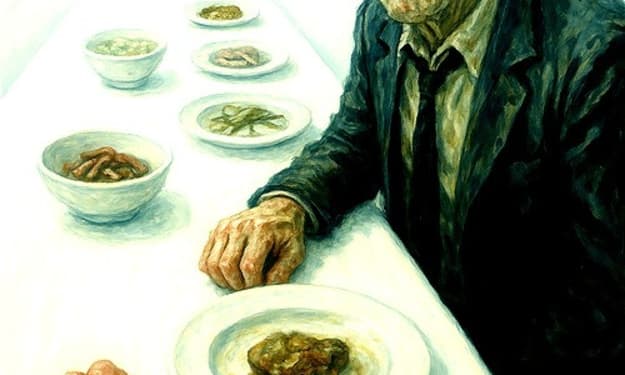

In between the shootings, stabbings, bludgeonings, rippings of flesh, gougings of eyes, and mastication of human shoulders and forearms, Romero spins a film about American materialism—or really, any materialism—the soulless, undead nature of a society choking on the glut of its own capitalist excess. The zombies, as one commentator called them, are “third-world horror,” symbolic stand-ins for the forces that may overwhelm the balance: the hordes of mass migration converging upon our shopping mall of sleek consumables and fast food, wanting a piece of the action.

Rednecks vs zombies (Dawn of the Dead - 1978)

They do not consume each other, of course. This is established in the confusion at the beginning of the film, during an emergency TV broadcast in a bustling studio (Romero himself appears in cameo). No, their appetite is only for the living. We have descended into hell, where the cast-off legions of nightmare rise to overwhelm us numerically, inexorably, shambling forward to eat our very bones. They may look like us, seek to be us, certainly consume us—but they are alien. And at death, we become them. We become the soulless thing of our own nightmares.

“When the dead rise, signore,” laments a one-legged priest hobbling on a stick, “it’s time to stop shooting. The war must end.” Ken Foree is equally reflective when his character recalls his grandfather, a Dominican priest of Macumba, who told him: “When there is no more room in Hell, the dead will rise and walk the earth.”

And what exactly defines “Hell” here? Is a luxuriant society of shopping malls, rich foods, fine clothes, and cheap gadgets just a covering for some empty state of false being—a thin veneer over decay? Are we consuming ourselves, or each other, in wanton abandon? The vision of a zombie apocalypse is the vision of a society collapsed because of its own cannibalistic tendencies. That inner core of repulsive appetite is hidden behind the shuffling façade of bourgeois contentment.

Dawn was co-scripted by Dario Argento, who secured financing in exchange for international distribution rights. Special makeup effects were devised by Tom Savini, who also appears as a biker renegade in the climactic finale—a nod to the anarchic nature of revolution, in which the lower classes may rise up to shake off the zombie hordes of the bourgeois, only to be consumed themselves in bitter irony.

Selected as one of the films labeled “video nasties” during the UK’s Eighties censorship crackdown, it was released unrated in the United States after initially receiving an X. By today’s standards it is hardly shocking. Cannibalism and flesh-feasts are de rigueur now, but then it was considered extreme. The film proved wildly successful, grossing millions beyond its $600,000 budget. Over the years, it has become lauded as a classic, “one of the best horror films ever made.”

Yet it remains, at heart, long, slow, and plodding—often tediously depicting looting and ransacking in the mall, with no truly compelling characters save Ken Foree’s Peter. Regardless, it is pioneering and groundbreaking—not only because of its unflinching brutality, but because it eviscerates our conception of who we are and what we represent: alive, dead, or in some liminal state between.

It was the dawn, not only of the dead, but of a whole new vestigial growth in cinema’s garden of shock. But, as always, you must dig beneath the surface for the body to arise.

Dawn of the Dead 1978

My book: Cult Films and Midnight Movies: From High Art to Low TRash Volume 1.

Ebook

My book: Silent Scream!: Nosferatu. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Metropolis, and Edison's Frankenstein--Four Novels.

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.