Crawlspace is a film that somewhat disappoints— for decades I had wanted to see it, having become interested when walking through a VHS store back in the 1980s, and also knowing the star, the turbulent late, great, and seemingly much-hated Klaus Kinski (whose equally famous daughter Nastassja has reportedly said, “I’m glad that he’s dead.”) as the star of Herzog’s remake of Nosferatu, as well as a standby for such shows as the classic Eighties horror-thriller anthology "The Hitchhiker" (Kinski played in an excellent episode, “Lovesounds,” one of the best in the whole series run).

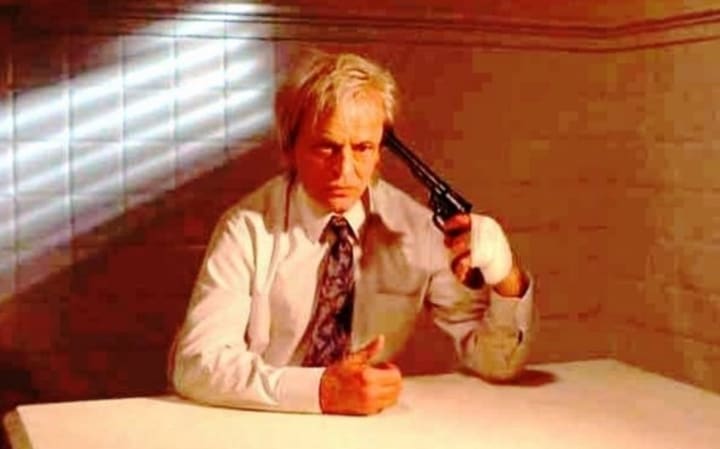

Here, he plays a landlord named Guenther, whose father, we eventually learn, was an escaped Nazi war criminal. To that end, we get old films of Hitler and Stuka dive bombers, which Guenther compulsively plays in his basement while fondling his gun, bleeding on his bullets, coming up to the edge of suicide, and tormenting his mute victim, whom he keeps in a cage. Since we begin this film by seeing him commit a murder with a designer trap that thrusts a spear through a woman’s guts, we’ve already been given the information that Kinski (who attuned audiences will know is the villain forthwith) is a bloodthirsty madman—he lurks in the crawlspace between the walls like one of his hungry pet rats.

Kinski manufactures various ingenious devices for his home—including a sort of motorized sliding board he can lie on and transport himself with. He turns down a prospective renter who does not interest him—instantly accepting a woman, Lori (Talia Balsam), as a tenant. We’ve already been treated to the image of Guenther/Kinski behind the iron grating of the crawlspace, his eager rat-like eyes watching everything lustily; he is spying on a world he can never, truly, be a part of. But is his insanity a convincing plot device? Certainly, it is an obtuse illness, one that sees him juxtaposed emotionally between states of grandiosity and complete, utter despair.

The house, like every house, is a metaphor—a stand-in for the mind of its owner. Like Roderick Usher, this house rises and falls, or at least exists, by dint of the chief occupant, Guenther, who we later learn, as a doctor, committed acts of euthanasia while practicing in Buenos Aires, much like his Nazi father, who used euthanasia on Jewish prisoners during human medical experiments. (We learn this from a detective called Steiner (Kenneth Robert Shippy), who, it is implied, clings to his past zealously, even affecting the clothing of the 1940s.) Steiner claims that Guenther killed his brother. Steiner ends up taking a dip in a deadly bath.

The other tenants in Mr. Kinski’s House of Horrors are bourgeois—a pop singer and several women terrified when Kinski lets loose one of his rats during a dinner party. The strange, low, mournful pop singing on the soundtrack gives an odd, jarring, modern counterbalance to what we see on the screen. Kinski is the heart and soul and subconscious of his domicile, sneaking through the passages, looking through the grates, crafting his deadly traps, and watching others make love, share in communal human warmth, and do other things that his psychosis and status deny him. He is the thought in the vast, cavernous space that is the house, the living brain, shuffling among social types he can never hope to emulate. At one point, dressed in a Nazi uniform, he observes that he has become his own “God, his own jury, his own executioner.” He worries that “society has begun to see me badly.” (Not, perhaps, an exact quote, but you get the picture.)

Yet through all of this, up until he dons makeup and proceeds to a bloody climactic resolution, we are none the wiser as to what the nature of this dark, festering, homicidal psychosis is. Is it that he is ashamed of his Nazi lineage? His “tainted” blood? Does the sin of the father become visited upon the son? His Nazi lineage seems to be something that makes him feel powerful; at the same time, he seems to identify with his legion of rats (almost echoing Renfield in Dracula (1931), Dwight Frye exclaiming that he sees “Rats! Thousands of them!”).

Rats, of course, were identified horrifically with Jews in Nazi propaganda films during the Holocaust. Guenther imprisons young women in a cage in his basement—it’s a confusing and unconvincing madness. But Kinski somehow delivers, as an actor. Sadly, the film fails to push the horror hard enough forward; it is a missed opportunity, as another critic has observed.

In a post-script, this film—written and directed by David Shmoeller, who also directed Puppetmaster (1990), among other cult horror films—is notorious for the legend of Kinski’s bad, difficult, and very eccentric behavior. Kinski was notoriously ill-mannered and ill-tempered, and reportedly by the third day of shooting started a number of altercations with cast and crew. He refused to allow Director Shmoeller to say “cut,” refused to say certain lines of dialog, and on and on, until the desperate Shmoeller and the producer appealed to have him replaced. Empire Pictures flatly refused, desiring Kinski’s bankability. This was when, reportedly, the “Italian producer” came up with the idea to have Kinski snuffed…

We’ll leave it at that. Kinski died of natural causes in 1991. Shmoeller made a short film later called "Please Kill Mr. Kinski," which I have posted, along with the original trailer for Crawlspace, below. We recommend seeing Crawlspace, as it does fulfill the obligation of being brutal, ugly, and full of the mad Mr. Kinski. And that, as they say, is a wrap.

Now I’m crawling into bed. But not, hopefully, with any rats.

Please Kill Mr, Kinski

Crawlspace (1986)

My book: Cult Films and Midnight Movies: From High Art to Low Trash Volume 1

Ebook

Print book

My book: Silent Scream! Nosferatu. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Metropolis, and Edison's Frankenstein--Four Novels.

“Silent Scream” plunges into the nightmares of early horror cinema, where shadows spoke louder than screams and monsters first took shape. Within these pages, you’ll find chilling new adaptations of Nosferatu, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and Metropolis — stories that defined horror before Hollywood ever gave us Dracula or Frankenstein. These silent terrors return with all their eerie atmosphere intact: crooked streets, haunted castles, vampiric fiends, and madmen who bend reality itself. For fans of classic horror, this is a resurrection of the genre’s roots — when every flicker of film could conjure a nightmare, and silence itself was screaming.”

Ebook

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.