Clive Barker's Nightbreed

Director's Cut [Broadcast Edit] (1990)

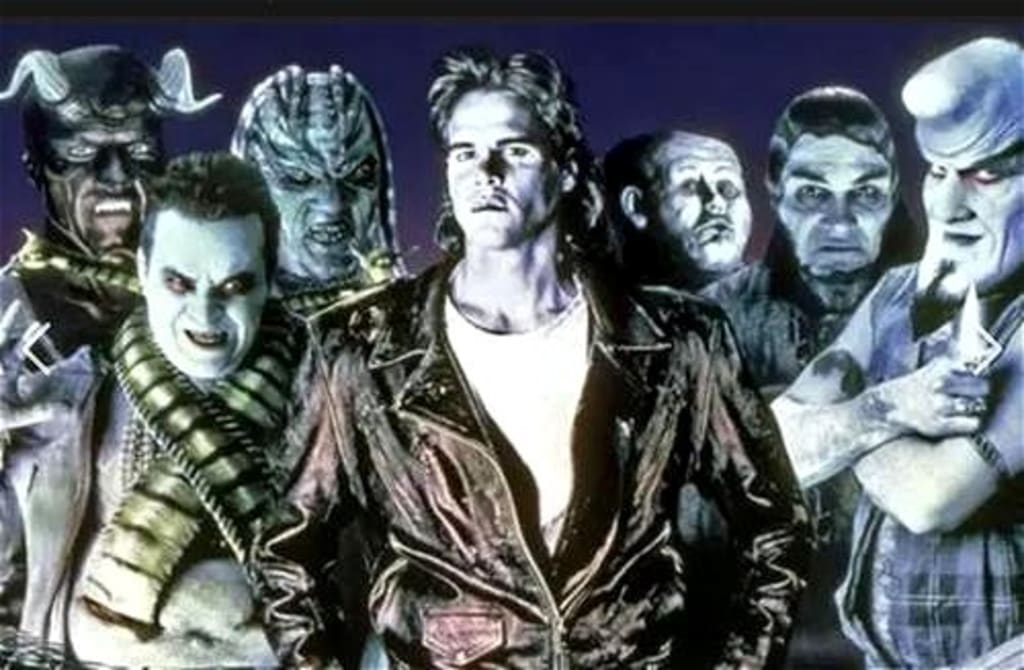

Nightbreed is one of the great, unheralded horror fantasies of all time. Directed by the dark, baroque prince of modernist fear, Clive Barker, from his own masterful novella Cabal, it features an incredible, icy, and utterly creeping performance by body horror maven David Cronenberg, as well as performances of equal weight from Charles "Altered States" Haid, Doug "Pinhead" Bradley, Hugh Ross, and others.

It's almost a perfect film; it does suffer from trying to be too many things. But should it be faulted for this? My chief complaint is that the soundtrack (by Danny Elfman) is too grandiose, too thunderous. It would have been better, in certain places, to have a more understated, darkly ambient score, instead of the wild, thunderous symphony that goes crashing and soaring with horns and strings wailing and bleating toward the heavens (and obviously, Hell as well).

Cabal—Nightbreed, as well, of course—is the story of lonely, mentally ill drifter Boone, who is conned by the psychotic, vaguely Patrick Bateman–like psychiatrist Decker into believing he is responsible for a series of heinous, ritualistic serial killings. Boone, played here with excellence in an understated performance by Craig Sheffer, believes this, and, under the influence of a strong hallucinogenic drug he believes to be lithium, tries to commit suicide—only ending up in a mental health facility. It is here he meets the freakish Narcisse, played with grotesque brilliance by Hugh Ross, who rips away the flesh of his own head in a Barkeresque fashion and leads the way for Boone to discover the yawning necropolis of Midian—a place wherein the monsters of history, forced literally underground by an inquisitorial world attempting the genocide of all supernatural mutants, build their subterranean kingdom. Lylesberg, played with dignified aplomb by Hellraiser's Doug Bradley, is their leader. But, above him even, is the bizarre, black-skinned, multihorned Baphomet.

Decker, who wears a horribly disturbing doll-face mask with bright black buttonholes for eyes and a lopsided zipper-mouth grin (that makes him look both horrific and eternally perplexed), chases Boone to Midian, where the other monsters, such as the bestial red Peloquin (Oliver Parker) and the bird-like, razor-quilled Shuna Sassi (Christine McCorkindale), initiate him into the tribe. Later, it is found that he fulfills their ancient prophecies, inscribed in cave paintings on the catacomb walls.

Lori (Anne Bobby) follows Boone to Midian—and so does Sheriff Eigerman, played with unlikable intensity by Charles Haid, also excellently. Eigerman leads a posse of redneck rabble straight out of a George Romero zombie epic in a full-on apocalyptic raid on Midian, culminating in many scenes of monstrous beings emerging from the depths below, to kill and be killed.

The creature effects and makeup design, representing the state of the art of the era, are really a sight to behold. Barker the artist operates from a visual tapestry that generates for the viewer a fantasy tableau of that world "right around the corner" from our own dystopian damnation. His characters are the "little men" who desire something more, some egress to the world beyond—pleasures undreamt of, that they can only barely glimpse. This is what drove Frank in Hellraiser to abscond with the Lament Configuration, and it is what drives Boone to the same degree, but ultimately, to a different ending.

The world of Midian, its grotesque monsters reeling from the attack by the human terrorists, is a world populated by the vast denizens of our nightmares—but it is a world uniquely us. It is the repository of our fantastical desires, sleeping among the dead refuse of our childhood hopes and dreams. André Breton noted in The Surrealist Manifesto that there comes a time in life when the capacity for fantastical dreaming dies, when it becomes interred in a burial ground not unlike the fantastical boneyard of Midian, where, as noted in Cabal, "the monsters live." Beneath even them, though, are the Berserkers—the guttural, bestial, confined demons of the deepest, darkest pits of our being—who are released to battle the killing posse of our egoistic, waking state: our adulthood, which blows dreams away at the end of a redneck's rifle.

But this is a bit much, perhaps. We release these things from the dark—these deathly dreams—to give ourselves an egress from the world of the mundane, the banal; the "suffocation life has prepared" for madmen and prophets, to borrow from Antonin Artaud. Barker has done that with this film; he has always done that—in book, film, and art. He shows us the perfection he exhibits, all the while taking us on a tour of one, many Hells—places the dreamer cannot access otherwise, though his sleeping brain may slip his body near the portals suddenly yawning wide.

This film, much like David Lynch's unjustly maligned Dune (1984), immerses us in a world beyond, and qualifies as nearly perfect and complete an entertainment, whether at its original running time or in a three-hour edit. Either way, it's a Hell of a monstrous ride into the heart of the dust-choked dead.

Nightbreed: Director's Cut [Broadcast Edit]

Follow me on Twitter/X: @BakerB81252

My book: Cult Films and Midnight Movies: From High Art to Low Trash Volume 1

Ebook

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.