Christine (1983): Stephen King vs. John Carpenter

When a Haunted Car Became a Clash of Creative Philosophies

## *Christine* (1983): Book vs. Movie

Stephen King, John Carpenter, and Two Very Different Ideas of Evil

There are movie adaptations that miss the point of their source material.

Then there are adaptations that understand the point — and deliberately drive in the opposite direction.

John Carpenter’s Christine falls squarely into the second category.

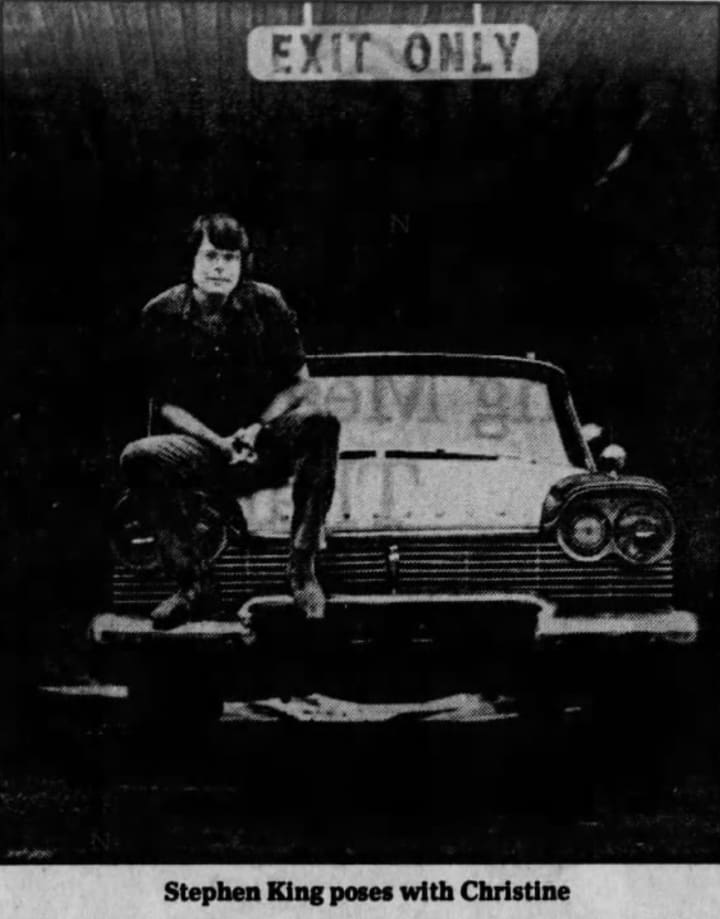

Released in 1983, the same year Stephen King’s novel hit shelves, Christine arrived looking like a straightforward killer-car movie. What it actually became was something far more revealing: a snapshot of two powerful storytellers with very different instincts about fear, control, and where evil really comes from.

Both versions work. They just don’t agree with each other.

Stephen King’s Christine: The Slow Poison

Stephen King’s novel isn’t really about a car.

It’s about obsession — the kind that creeps in quietly, convinces you it’s helping, and then replaces you piece by piece.

Arnie Cunningham doesn’t become dangerous overnight. King shows us the transformation inch by inch: the new confidence that feels earned, the edge in his voice, the way his longtime friendship with Dennis starts to erode. Christine isn’t just killing people — she’s isolating Arnie, reshaping him, hollowing him out.

A crucial element of the book is Roland D. LeBay, Christine’s former owner. In the novel, LeBay isn’t a footnote; he’s a presence. His cruelty, possessiveness, and voice linger, raising the possibility that Christine’s evil is not mechanical at all, but spiritual.

That ambiguity matters. King wants readers asking whether Arnie was taken over — or whether Christine simply gave him permission to become someone worse.

In an interview at the time, King acknowledged that this question became a major point of debate during the adaptation process:

“That’s one of the questions with which the movie people started to wrestle. Was it LeBay, or was it the car? I understand that their answer is that it was the car.”

That answer changed everything.

John Carpenter’s Christine: Born Bad

Carpenter wastes no time.

His *Christine* opens on the factory floor, where the car kills a man before it even has an owner. There’s no mystery, no slow corruption, no psychological hedging.

This car is evil.

Period.

Carpenter strips away much of the novel’s interior life and replaces it with pure cinema: headlights glowing like eyes, dents snapping back into place, fire rolling down the highway to the sound of rock ’n’ roll. The horror isn’t creeping — it’s charging.

And Carpenter never pretended this was a deeply personal project. He’s been candid in interviews over the years, admitting that Christine wasn’t something he was emotionally attached to:

“To be very frank with you, I wasn’t in love with *Christine*. I didn’t think it was that frightening. But it was something I needed to do at that time for my career.”

That pragmatic approach shows. Carpenter isn’t translating King’s inner monologue — he’s building momentum. The result is a film that feels colder, cleaner, and more ruthless than the book.

Stephen King’s Uneasy Distance

Stephen King has a famously complicated relationship with film adaptations of his work, and *Christine* sits in a strange middle ground.

While he was supportive during production, King later grouped Christine with adaptations that left him emotionally unmoved. In a 2003 interview, he described certain films based on his work as technically competent but empty, adding:

“They’re actually sort of boring. Speaking for myself, I’d rather have bad than boring.”

The criticism isn’t about craftsmanship. It’s about loss.

What King missed was the tragedy — the slow collapse of friendship, the sense that Arnie’s soul was slipping away long before bodies started piling up.

Two Creators, Two Philosophies

This is what makes *Christine* so fascinating more than forty years later.

* King believes horror comes from erosion — identity wearing away under pressure.

Carpenter believes horror comes from motion — something unstoppable bearing down on you.

King’s Christine asks *why* obsession destroys.

Carpenter’s Christine asks "how fast it can kill."

Neither man ever fully embraced the finished film, yet the movie endures because of that tension. It’s polished, mean, and unforgettable — even as it sidesteps the novel’s emotional core.

Sometimes adaptations succeed not by honoring every idea on the page, but by committing completely to a different one.

Christine doesn’t belong entirely to Stephen King or John Carpenter.

It belongs to the argument between them.

A stylish, ice-cold adaptation that trades psychological depth for cinematic momentum — and leaves rubber marks all over 1980s horror.

**Tags:** Movies of the 80s, Christine 1983, Stephen King adaptations, John Carpenter, 80s horror, cult films, book vs movie

About the Creator

Movies of the 80s

We love the 1980s. Everything on this page is all about movies of the 1980s. Starting in 1980 and working our way the decade, we are preserving the stories and movies of the greatest decade, the 80s. https://www.youtube.com/@Moviesofthe80s

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.