Apron's Folly

A ghost story

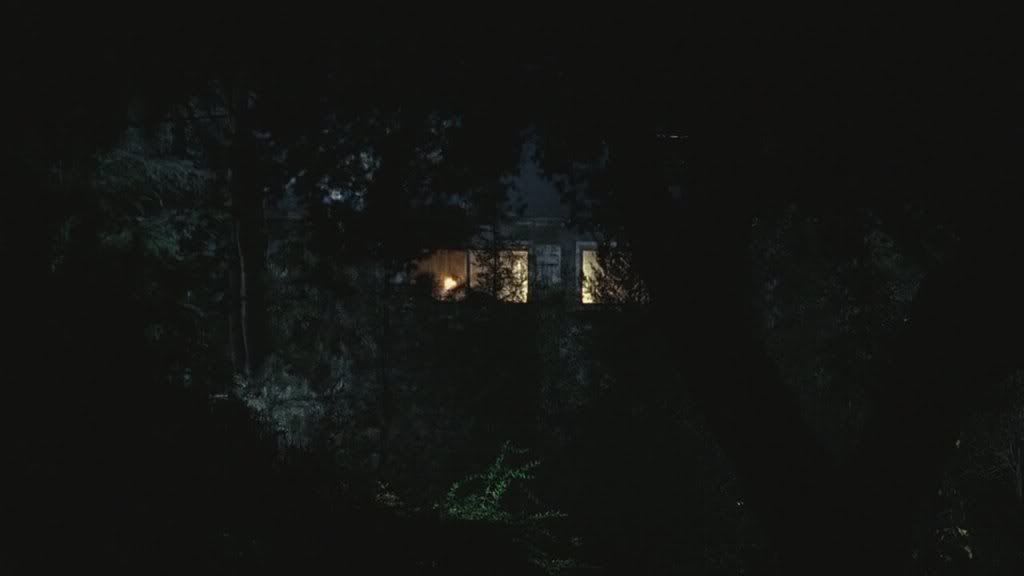

The cabin in the woods had been abandoned for years, but one night, a candle burned in the window. It was an early summer night, rich with the smells of wild honeysuckle and apples fallen off their trees. The cicadas whirled their music through Grover's Field, and under the starlight, the six of us had wandered into nature to get drunk and sweaty and carefree. But then, after the first libations were poured, Mac looked over towards the shell of Apron's Folly, and exclaimed, waking us up from our revels.

"Oy! There's a light in there!"

We glanced over, one after another. For my part, I think I was the very last one to turn; Joanne in the moonlight had been giggling at something I'd remarked, and stood close enough to share her heat with mine. Seeing her expression change from mild confusion to something amounting to concern, I looked over as well.

"Blimey--I'm not seeing things, lads, am I?"

Nobody answered Mac. He wasn't seeing things: in the top left window of Apron's Folly, a soft little orange glow tumbled up and down with the wind. It was a house that had stood for almost seventy years, and would stand for a good seventy more; nobody wanted the place, and anybody from out of town who tried to buy it soon gave up. It was still in decent condition; parts of the siding were weather-blasted and ramshackle, and a few boards in the roof had caved in, but the bulk of it stood unphased by its inoccupancy. The boys from Stapleton who'd ventured inside--always during the day; the extent of their bravery--swore boisterously that they'd've moved in themselves if they'd had the money. The wallpaper still sang of flowers; the kitchen still held its appliances; the floors were dusty and cobwebbed but nothing a little bit of elbow grease couldn't fix.

But then, nobody wanted to venture near it after dark. Even coming to Grover's Field was almost unheard of--it was why the six of us had done so: privacy for our debaucheries.

"Oy?" Mac sounded shaken, unable to look away from the wavering light. "Am I crazy or am I not, you lot?"

"You're not," I said, my deep voice a source of reassurance to the rest of them. They all relaxed, I noticed, and seeing Joanne half-turn gratefully my way reinforced my calm spirits. "There's a light in there. Probably some high schooler on a dare. Leave them be, eh? We've still got the brandy and some cakes."

Moira laughed, turning back to the party first, and with her, William followed. Bess's nervous little form didn't move until Mac wrapped an arm around her shoulder, and then she let herself be guided back to us. I smiled, catching Joanne's gaze again, and we went back to our checkered tablecloth, spread over the dirt, and sat for our midnight picnic. William opened the brandy to a cheer from the rest of us and poured it out among our glasses. But try as we might, the night had gone cold, and we could feel the vast emptiness of the field around us.

"Do you really think it's a high schooler?" Moira asked after we'd sat and drank. I realized with some annoyance that it was the first thing anyone had said since we'd regained our nerves. The five of them looked at me; we hadn't regained anything.

"I do," I answered, casting a glance at Joanne as I smiled. She smiled back, but clouds had formed in her blue irises.

"Why?" William asked.

"Well, what else can it be?" I laughed. "Pass me some of the wheat cake, Bess, would you?"

Bess didn't move, looking at me with large, sagging eyes. Mac reached over from next to her, handing me a piece.

"Do you think it could be a ghost?" Bess finally said.

"A ghost?"

"Toss!"

"Oh, Bessie, don't be ridiculous!" Moira scoffed.

"I just meant--"

"Bess, dear--"

"Well why is there a light--?"

"It's a high schooler, like he said--"

"Why is there a light?"

"Bess," I said calmly, stopping them. Bess shivered and hugged herself close, and Mac sighed and tossed his arm around her. They all looked towards me again, and I took a moment to enjoy a bite of wheat cake. "Whether it's a high schooler, or a ghost, or something else entirely: it's in there, and we're out here. We've got a fine night around us and terribly lovely company. We've got drinks and lurid thoughts that nobody can stop us from thinking. We're safe."

I let a demonic smile slide up my cheek, enjoying seeing the coward blush and realize how close Mac had sidled up alongside her. Joanne cleared her throat but said nothing, glancing up into my eyes every so often as she drank. I met her gaze openly, and soon a blush spread along her face as well.

"Well, since there's nothing more clichéd than the terrified lass jumping into the strong man's arms," Moira hummed, "and since I need a reason to pounce on William anyway, tell us about your ghost, Bess."

William spluttered; Mac laughed at him. Joanne sighed, holding out her glass to me for more brandy. I obliged: she moved closer to my side.

Bess looked pale in the moonlight.

"Don't you know?" she mumbled. "Don't we all know, I mean? Everybody knows about Apron's Folly."

"Oh, indulge me, kitten," Moira smirked.

"Easy," Joanne said, watching Bess crumble. "Leave her be, Moi."

"Well, now I am in the mood for a ghost story," Mac chuckled, petting along Bess's arm. She snuggled against his side, relaxing. "Tell us one, Will."

William looked over from admiring Moira's figure. "Hm?"

"Apron's Folly," I said, saving them the trouble of banter, "was initially planned by Sir Shelby Apron, back in 1777. His manor stretched out over Handred Court and the south side of the Killian Woods, and took up his attention in full; it burned in 1885 after the dry spell that caused so many townsfolk to move out towards Ferredan. Sir Shelby's great-grandson, Marcus, rediscovered the plans and built Apron's Folly seventy years back, as it was intended to be: a summer home to retire to with his wife and three children. It was named that for the sense of joy it ought to have given them--and yet, it earned its name more from the ruinous nature it took on.

"Reportedly, the first day Marcus Apron and his wife Constance went to their home, their horses reared up and broke the harness to their carriage. Luckily nobody was hurt, but while their servant-boy ran up the road to Wilmington, a storm grew from nothingness overhead and erupted onto them. Marcus and Constance Apron did their best to be patient and wait, alone on the roadside in the greying evening, but their children were restless and bored, and one of them--Simon, their youngest--broke out of the carriage and ran off to play in the rain before either parent could stop him. When he was caught again, he was soaked through to the bone, and by the time they all got to Apron's Folly with the help of townsfolk, the boy was sneezing.

"Almost as if it were planned, when they finally got to their new summer home that night, the rain stopped. It was late, and they were hungry and tired, and the good people of Wilmington helped them settle in with some comfort. That first night, nothing was wrong, save the occasional cough and sniffle from Simon. Every child has had a summer cold; they're a nuisance more than anything.

"When Marcus and Constance got up, they found two of their three children anxiously waiting to go play. The third was bed-ridden, and they soon learned that he had a steadily-increasing fever that climbed and climbed. They piled blankets on him; doctors came to treat him; there was no reason he should've been ill beyond a common cold. Marcus, who had been out in the rain chasing him, was fine. But the boy grew worse over the course of June.

"On the last night, before July reared up and struck the heat of the season to full bloom, Constance stayed up reading to her youngest, and at the stroke midnight, a single cry from her awoke Marcus. He ran to Simon's room: Constance was weeping, sitting on the bedside of her son, holding a mirror to his chin. The mirror was fogged with a single expelled breath, but nothing more. The boy's eyes were glassy, and the room was dark with a myriad of shadows."

Bess shivered against Mac, one delicate hand finding his and clutching it; he smiled at me, and I nodded my you're welcome as subtly as possible. Moira sipped her brandy, shifting around to sit in William's lap; Joanne stared up at me silently, composed and beautiful.

"The child died; the parents mourned; a plot of earth was dug and filled up. They buried him out in their extensive back yard--out on the edge of the woods. They didn't want the trouble of traveling back home--not in the summer; not in the heat--so he was buried behind the home, and they stayed put, letting their remaining children out into the woods to ramble, trampling over the grave of lost little Simon every single time.

"The days passed: the children found a brook to go splash through each day, and Marcus and Constance spent the time in each other's company, in gardening--the areas not near their son's grave, that is--and in reading and other such adult leisures.

"At night, however, there was unrest. It started as Constance mumbling in her sleep; just a few words, here and there; fragmented sentences without any meaning. But they woke Marcus regularly, and so he was awake to see her affliction transform into full somnambulism. Sleep-walking; that is the simpler term for it. She would get up, pace down the hallway, down to the children's individual rooms to check in on them. The children slept soundly through it all, but Marcus was perturbed; he followed her, trying to ascertain if she was fine. All she did was coo over them--kiss their foreheads, tuck them in--but then she got to Simon's room."

I let the pause grip the air, watching my friends. They watched me silently, our feast forgotten for the midnight ants to ravish.

"She would do the exact same thing," I continued slowly. "She sat down on the bed, bent over a shape that wasn't there, and would kiss and stroke a forehead of nothingness. As if she could see him still in the empty bed.

"And, unlike the other rooms, Marcus had to gently--though forcibly--help her to stand up again and leave the room. He had to, every single night: she never would on her own."

I drank my brandy, and Joanne offered to refill it for me. I smiled my thanks to her, and she answered with a knowing politeness about her gaze.

"The difficulty of this emotional journey Constance took every night began to weigh on Marcus. After all: she slept soundly, but he was awake for twenty minutes or so, every night at midnight, reminded of the void in their home. Sometimes it took longer; she began to resist, with increasing vigor, his attempts to pull her from Simon's bedside. So, one night, towards the end of July, Marcus locked the door to Simon's room.

"On her rounds, Constance went through as normal, kissing each child's face and tucking them in. When she got to Simon's door, upon finding it locked, she swayed, and brought up a hand, beating against the wood. Beating again, and again, and again, in a low staccato, again, dead weight on dead wood, again, pounding without any strength to be let in.

"Marcus led her away from the door, and as she shuffled back to their room, he heard something. A small creak in the wood, beyond, in Simon's room. Just a little thing: it could've been his tired mind, or the boards shifting to accommodate the parents on their journey back to bed. But it was there, that tiny sound of movement.

"Then, precisely one month after Simon's passing, on the last day of July, before the leaves turn red and the summer falls with the reaping scythe, Marcus was not awoken by his wife. Reportedly, he had a dream, and in that dream he could remember nothing save Constance murmuring something into his ear. A few words--barely distinguishable from the other sounds of the night. She said:

" 'Simon's calling for me.' "

"When he woke up, she was not in bed. She was not preparing breakfast; she hadn't decided to tend to the garden first-thing in the morning. But as Marcus walked out along the grave behind the house, he saw Constance.

"She stood in the window of Simon's room, overlooking that lonely hillside into the forest, the glass heavy and fogged with her breath."

Bess trembled; Mac gave her arm an encouraging squeeze. Moira leaned in, intrigued. Joanne tore off some wheat cake for herself.

"Marcus ran back inside; the other children--Liza, his oldest, and Callow, his middle child--were both yelling from upstairs. He ran up: they were pounding on the door to Simon's room, saying they heard their mother inside, screaming.

"The door was still locked. The key remained, unmoved, in Marcus's dresser; he grabbed it and swiftly opened the door.

"Constance laid in bed, peaceful, arms crossed and composed. Her lips were slightly parted to expel her breath. Her eyes were open, staring at the ceiling with glassy indifference. She was dead, and cold, as if she'd laid still all night.

"They buried her next to her son, out behind the house.

"The children grew restless, wanting to leave Apron's Folly, but Marcus fell into such a shock at the death of his beloved wife that he could not make good on his promise to ride out to the nearest town and send word for their servants to bring them away from their summer home. They had given word not to be disturbed there, after all. To have 'three months of bliss' in their country getaway. So the surviving three remained, and the children ran to a creek they'd found in the woods, staying out all day and into the night, leaving Marcus to sit, alone, in his quiet house.

"He locked the door to Simon's room. He closed the blinds on the curtains, so that nobody could see into it from below. A week after Constance's passing, he moved all of his things out of their bedroom and into the living room downstairs, and locked the door to his former bedroom as well. He never explained why to anyone.

"Then, one night in the middle of August, the children did not return home from the creek."

Joanne shivered in the breeze. I paused to take off my suit-jacket, offering it to her. She took it, nodding thanks.

"Marcus only realized it around ten o' clock, by which time it was far too dark out to go looking. But he sprinted out, leaving a candle in the window of Apron's Folly lit for his return--rather like we have now. He ran over the graves of his young son and his wife, ran out into the wild woods, sprinting until he realized he had no idea where the creek was: he had never ventured out with his children to it.

"Hearing the water rush somewhere below, Marcus ran through the trees until he found it. The creek was nestled in the heart of the forest, in a small clearing where moonlight mixed with the water and created another sea of stars. In the darkness, Marcus cried out, making out the shapes of Liza and Callow, lying half-in the water.

"But as he ran down to them, he stuttered and paused: in the water, too distorted by motion to see, seemed to be two other figures, hunched over the children's bodies.

"Marcus gathered them up--they were still alive, breathing faintly--rushing back home at once, not looking at the water. As he got back to Apron's Folly, he saw the curtains drawn back from each and every window, and a fog of breath fading on the illuminated glass upstairs.

"Setting the children down, he ran up the stairs. 'Who's up here?' he called. 'Who is here?'

"But there was no answer. He went through each room, searching, holding his candle high and finding nothing--and finally unlocked Simon's room. The curtains were pulled back, and moonlight through the glass reflected all the dust in the air.

" 'Show yourself. Who's here. Where are you?'

"The room was still. Marcus shuddered, looking around, straining to see something--anything--and finally moved over to the window, looking out over the backyard, and the graves.

"As he did, he saw his own reflection, glimmering in the candlelight. And something standing behind him, moving in the room.

"His gaze darted around; nothing there, save the dust swirls--

"A breath sighed against his ear from behind him, coming off the glass.

"Marcus fled the room, not stopping to even lock it. As he ran downstairs, he saw his children in the living room where he'd made up a new bedroom, their faces pressed up to the window, suffocating it with foggy air. As he entered, they fell to the floor, dead, and where they had been were two outlines in the glass--outlines of the children, caught in their final breaths, facing him.

"Marcus left Apron's Folly, running up the road, running seven miles to Wilmington and dropping down in exhaustion at the foot of the inn. He was brought inside and kept on a couch for a week until his fever broke. When he could speak coherently, he told them his story, and they offered him a room, since he adamantly refused to go back to the house. That night, they heard him scream--though it choked off, midway through--and when they went up, they found him convulsed and bulging with fear, as dead as his family. He'd covered the mirror in his room--one on the dresser that faced the bed--but had done a terrible job of it. The blanket had slipped off onto the floor, leaving his empty eyes staring into the glass.

"Apron's Folly, with no tenant willing to claim such tragedies, became vacant for many years, and fell into ruin. There was a building project, about ten years back, to renovate it for a family with some wealth that didn't much mind if some people died there. The construction was fine, until a man named Flint slipped and fell from scaffolding along the second floor, breaking his neck in the garden below. He'd been replacing the windows.

"A few people have lived in it since. The affluent family lent it to travelers who would rent it for a time and give it up again. People in town don't come near it, and I can't say I've seen anyone living in it for the past two years. I'm surprised the high schooler chose candles, instead of a torch--but then, perhaps they didn't have enough batteries to keep it lit all night, or however long they were dared to go in there."

I ended my tale, smiling politely at them and drinking the last of my brandy. Joanne offered to refill it; I shook my head no this time, and instead murmured a request for water, which was obliged. Mac was quiet, gazing over again at the candle; Moira reached behind herself, petting William's hair when he laid his head on her shoulder, waiting as if I had more grisly details.

"Th-That really happened?" Bess asked, eyes as huge as the summer moon.

"Of course it didn't!" I laughed, "I made it up based on what I heard and added enough to get you close to Mac. It's all a lie; a kid died there by accident and his parents went mad with grief. There's no records of anyone else dying there, besides that poor builder--again, an accident, brought on by wind and rain. You know how it is in this part of the country, Bessie; the weather's got more spit to it than ruffians in one of those American saloons. The end. It's tragic reality, not a ghost story."

They didn't let out their pent-up breath.

"Oh, it's all just hogwash! I made half of it up, and heard the rest from folks who made up their halves. Nothing to it," I said, chuckling silently at their nervous expressions. "So, shall we go i--?"

My voice died in my mouth as I turned to face Apron's Folly again. My eyes widened, and all at once I could feel the night air cooling the sweat along my back.

In the window, glimmering in and out of visibility with the flickering candlelight, six dark silhouettes stood watching us.

I was barely aware of the low moan that escaped my throat as I darted up and stumbled away from the house in the distance. The moonlight crackled over the window, disrupting the image-- in a moment, Joanne was at my side. The others looked terrified, then burst into bouts of nervous laughter.

"Come off it! Oh, God, he had me going!" Moira exclaimed, giggling and turning to hug William's neck. Bess started to laugh with her, squeaking as Mac finally let himself be courageous and kissed her cheek.

Joanne, looking up at the expression on my face, did not laugh.

"What did you see?" she murmured.

"A trick of the light." It didn't sound convincing at all. But I smiled for her, taking a breath and walking back to where I'd been sitting. The moon passed behind a cloud, and I narrowed my gaze towards Apron's Folly, and the window.

The candle wavered behind the glass, alone.

"Good Lord, but you're quite a good showman!" William chuckled. "I'm half ready to invite you to my sister's next dinner party!"

The smile stayed stretched across my cheeks as I sat again, turning away from the house to face my friends.

"Do you know any other ghost stories?" Mac asked, bemused. "Not that that one wasn't wonderful, but perhaps for next time we come? You'd make a fine entertainer, my friend."

I shook my head politely no--I did not know any others, nor wanted to--and went to refill my water. Something in my brain turned my face towards Apron's Folly.

The night went dead still.

Two shivers rolled their anemic hands down my spine before I realized that Joanne had said my name. The others were getting restless.

"Come on; you don't have to keep selling it," Bess mumbled. "It's already a spooky enough house."

I nodded slowly, then gathered what things I'd brought and stood up to leave.

"Where are you off to?" Moira asked.

"Going home. Or, rather--" I turned to Joanne. "I thought I might accompany you home, if you wish? Some good company to walk with?"

Joanne gulped. She knew, better than any of them, that something was wrong.

"Going home so early?" She crafted a lovely smile under the midnight moon. "Sure we can't entice you to stay?"

"My dear," I said softly, "if you allow it, I shall admire your beauty the whole way home. If you would permit, I would be glad to take a more scenic route home. A lovely, long walk under the stars."

Away from here.

Joanne blushed, then stood, smoothing her dress, and after a moment took my offered arm.

"Oh, such a good friend!" Mac called to us. "Scare us half to death and leave us here."

I let myself laugh, hoping my laugh didn't come out as shaken as my nerves. "Well, perhaps you boys might take a hint and offer the same to your dates!"

Moira was the first on her feet, dragging William up, then Mac had gathered Bess up more gently. They packed their things, and I turned with Joanne to go.

"Perhaps we could tour Apron's Folly, Will?" Moira giggled. "I might be so frightened I'd cling onto--"

"NO!" I barked. The five of them jumped. I didn't bother to hide my expression anymore: wide-eyed and changed. "No. Leave it for daylight."

They said nothing, and without another word-- I glanced back towards the house. Then I turned and walked quickly away, guiding Joanne through Grover's Field.

When I'd looked again, sitting there, the six figures had reappeared. As if they were stains trapped in the window, illuminated only at an angle I could see.

Except one of them--a small child's silhouette--had pressed his hand up against the fogging glass.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.