I suppose he grew fond of me in the end, though I swear I did not invite the old mans trust through ill intent. He was rich and alone, and I too was the latter, and though I understand that admitting it paints a somewhat seedy perception upon my association to him, I certainly was not rich. It had come to my attention that the old man had no family, no friends, and scarcely an associate with which to share the last few months of his life, and my heart ached on his behalf. This information was slipped to me by a nurse compelled to share due to my “kind face”, who had visited the factory in which I worked and the old man owned after he’d had something of a funny turn. It only took a glance upon his haggard face with its cheeks as pale and gaunt as chalk cliffs, for me to determine that his personal hourglass was emptying out its last few grains of sand.

I offered him tea then, and I recall that he only grunted with thanks. The next day I did the same, and the next, and the following six. On the ninth day, I bought him cake. By the thirteenth, I received an actual thank you, and with the second cake taken to him on the twentieth day, he asked for my name. I left his office after this occasion with enforced humility, though a strange victory followed on a tailwind. So I carried on this innocent routine of cake, of tea, of grumbled thank yous, with - as I’ve said before - no mercenary aim, until one day he requested my prolonged presence. He required my help and stressed that I possessed something that he did not: strong fingers, required for the purpose of turning the pages of the heavy financial logbook on his desk. I learned from this that the old man had an unassuming sense of humor, dappled with cynicism, and aged with little social interaction. I politely laughed and stood behind him, turning the pages at his request as he hunched over the book and scratched his quill over the paper. I did not absorb his workings; I remember simply remarking that his writing was thin and sharp, like skeletal branches casting shadows across an expanse of grey, melting snow.

It was during this encounter that I noticed something else about him. It might have been a tick or some kind of senile habit, but with every page that I turned, the old man shivered. It wasn’t a mere tremble of his shoulders in retaliation to the draft of January air that filtered into his office, but a sudden jolt that quaked the entirety of his frail body, and clattered his brittle bones to the extent that it must have conducted quite the rattling cacophony to his own ears. I could not exaggerate this retelling, believe me, but it was such a severe motion that he must have been aware of it. Surely he knew he did it. It unnerved me, concerned me even, though I didn’t dare enquire.

The old man required my assistance with this less-than-arduous task of page-turning every Friday afternoon, and to begin with, I was glad to oblige. He poured over figures, attentive to every decimal, thorough and vigilant. I was aware of his wealth, and I’d suspected him to be a miser, but now my suspicions had been confirmed. He was ruthless with his counting, rigidly precise with recording every minor transaction. One would have thought that his meticulous routine was something he enjoyed, given the detail with which he carried it out, though I came to believe that I was very wrong in thinking this. In fact, he seemed to resent it. He would stumble from his office at the same time every week, and like a vulture, he would eye me on the factory floor. His finger would crook, beckoning me up to his aid, and I remember how at first, his shriveled features would twist with displeasure. I went at his request and stood behind him. When instructed, I would turn the heavy page. Every time, he would shiver. My concern rapidly turned to irritation.

After two months of this, I was summoned later than normal. We remained in the factory office past its closure, with my laborious page-turning and his wretched shivering, and as it was dark by this point, and he was so old and decrepit, I offered to walk him home. I predicted (or rather hoped, for by this point in my relationship with the old man, my pity for his lonely soul had dissipated and been replaced by perturbation, though I was under courteous obligation to not rip away my assistance, for he was very much my senior, nevermind my respect for his tragically isolated life) that he would decline, though to my self inflicted chagrin, he accepted. I remember the hardness of my swallowing, the plummet of the lump in my throat akin to an elevator cut of its chords.

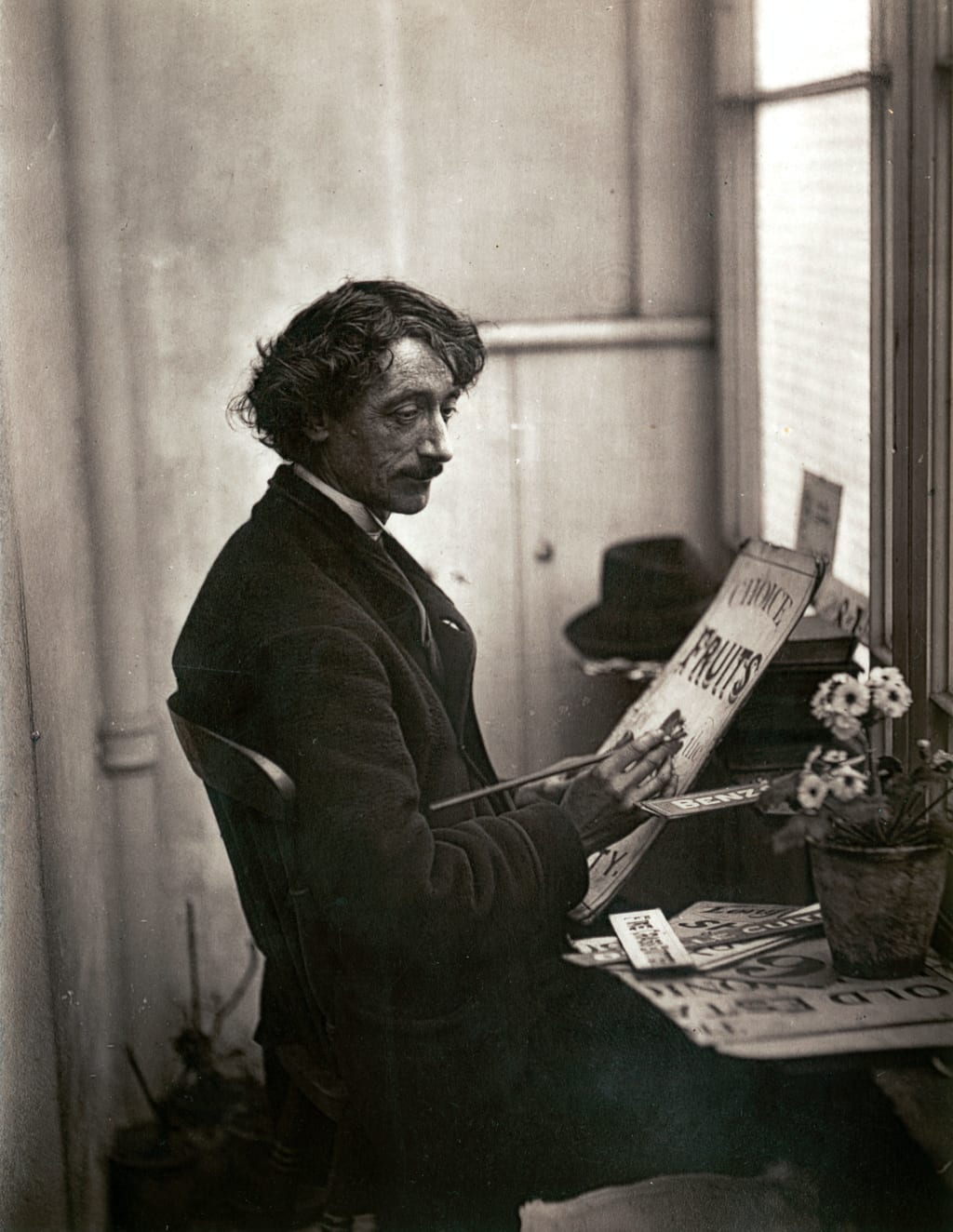

His pace was so terribly slow, even with the aid of his cane, and I thought to myself with distasteful disbelief how remarkable it was that he had lived this long. I offered him my arm, begrudgingly I might add, and he took it with a surprising grip that hindered me and weighed me down. I was courteous enough to ask for his permission to smoke and was relieved when he granted it. He made conversation with me, small talk, inquiries into my life. I told him that no, I had not married, nor did I plan to, and that I hoped never to have children. He asked if I had any family at all, and I informed him that I was all that was left. I told him that the only color in my monochrome day-to-day were the paintings I created, and that the gentle whisper of my paintbrush stroking against a canvas was the nearest thing I had to another breath to dance with my own. I knew that when speaking it all out loud, I’d painted my greatest masterpiece yet; the lament of an utterly wasted heart. He paid interest in my sorrowful existence, however, and I allowed him to pry. The white smoke that exited my lips along with my life story completed the picture with a translucent frame against the darkness of the night.

When I left him at the gate of his great house, he thanked me verbally, and I took my own path home. Back to my lowly bedsit, chaperoned only by a winter wind.

I dare say I predicted the amiability with which he greeted me in the factory the following day. His crooked index finger did not hook a beckoning motion, instead, he waved. I went to his office, invited rather than instructed, and I recall him calling me ‘my dear boy’. Strange, now that I think of it, that his fondness for me grew while mine for him went stale. He stayed in this jovial disposition, growing more affectionate even still, and I soured further, my stomach contorting with disdain with every beckon to his dust-caked, dingy, hovel of an office. Still, I obliged. My motive by this point had become some strange method of torture, and every moment I spent witnessing his festering life served as a reminder: I lived alone by choice and was kind to no one. I was irrevocably better alone.

His most pleasant saw him bring me some disgusting cake to our Friday meeting, just as I had bought him cake, in the very beginning. I ate it with faux enjoyment, and he cut me another dry slice that I did not want.

The old man died the very next day.

At first, I felt a strange weight of grief. His absent iron grip on the crook of my arm hung from hooks in my heart, and at moments, I found myself praying that he’d reached some level of heaven. My mourning was fleeting, and my mind found a materialistic passage to ponder upon the happenings of his fortune. You can imagine my sheer stupefaction when I was informed that it was mine.

The old man left me a grand sum of twenty thousand dollars. I was sick with the reality of it. Perhaps it was my lifelong status as a pauper, but this newfound wealth felt more to me like a curse than a blessing. I questioned his sanity. I questioned my own. I questioned the events leading to this, and furthermore, the future awaiting me that was so harshly altered now.

I restlessly took to the old mans office in the night. I opened the logbook that I assisted him with for so many tedious days. I recognized now that his intent was for me to learn. Despite the depth in which I found myself, having learned nothing at all, the familiarity of the heavy book settled my archaic thoughts. An obsidian paperweight pinning down a plethora of frantic slips of individual fears. I came to realize that my life wasn’t altered by this fortune, it was reinforced. I could remain in my desired isolation just as the old man had. The only difference now was that I was rich. Along with the paper upon which I painted, money was to become my second solace. They were both lovers I could hold between my index finger and my thumb, adore for moments only, and exchange without regret. I settled with the comfort of it all and opened the book.

There was something wedged within its first few pages. Another book, a quarter of the logbooks size, black-bound, each page heavily thumbed. I suspected it was just another recording of the wealth I had inherited, though there was something about its leather casing that weighed heavy in my palm. Like tar. I succumbed to curiosity, and with opening it, my eyes fell upon a set of strange words:

“With every cent spent, the specter of my predecessor lingers a little longer.”

Perplexed and pale, I turned to the next page.

“He taught me well. I wish he’d leave me be.”

And the next, turned to with not-so-strong fingers that trembled as they went.

“The familiarity of his stern gaze upon me gives me no comfort, but conducts a shiver through my very core.”

My heart threatened to burst from the pathetic bars that contained it.

“I have reluctantly selected my successor.”

My blood turned to lead, my skin to cold marble.

“I am free of guilt; the young man’s life is less than remarkable, and his lonely soul is already rotten. I have no qualms in bargaining with it.”

***

I maintain the weekly routine of counting my obtained fortune, dreading every transaction. There is no joy in spending it, and I am exhaustive with every minor purchase just as the old man was. I have filled two pages already. I turn to the next.

A fragment of him remains, lingering in each record of the money I am terrified to squander. His shadow, like black smoke, looms in the corner of the room with its disapproving eyes upon me, its crooked finger hooked towards my quill. I dare not engage, though my resistance manifests in a physical sensation that I am not so able to ignore. A shiver.

As I said, I did not invite the old mans trust through ill intent, though I know now that the same could not be said for him.

As I said, the old man grew fond of me in the end.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.